Michael Kraus, School of Management, Yale University

Michael Kraus, School of Management, Yale University

February 2017 – Emotions have been called the grammar of social life—people use expressions of emotion to communicate internal states to others both rapidly and accurately. Emotions serve particularly crucial functions during social interaction because they convey information, sometimes unintentionally, about our own internal goals and motivations. Without the ability to express and read emotions, social interactions would be much less smooth and often break down completely.

My interest in studying emotions and their roles in social life emerged during graduate school at the University of California (UC) Berkeley. There, I worked with one of the leaders in emotion research, Dacher Keltner, primarily on issues of social class inequalities. In that line of work, emotions kept surfacing as a key player in driving differences between people who are higher versus lower in the economic hierarchy of society.

I later received postdoctoral training at UC San Francisco (UCSF) under the tutelage of another authority in the field of emotion, Wendy Berry Mendes. At UCSF, I studied psychophysiology methods, and have continued to use these tools to better understand how emotions link mind and body in reaction to threats and opportunities in the environment. My views on human psychology have been deeply shaped as a result of this training: I now tend to see and understand complex patterns of social influence and group conflict in terms of their underlying emotional dimensions. More specifically, much of my research is built on the assumption that emotions are not merely reactive feeling states that are the result of decisions we make. Instead, they are active drivers of our decisions, shaping the ways in which we decide to help or harm out-groups.

In what follows, I offer some highlights from my research on how emotional expressions communicate information and how social hierarchies affect empathetic processes.

Tactile Expressions Support Teamwork and Cooperation

The importance of touch in social processes and emotional bonding has been largely overlooked by researchers. Some non-human primates spend upwards of 20% of the time grooming, a behavior primates rely upon for its social functions and ability to solve conflicts—a gentle touch is sometimes enough to prevent an aggressive encounter from escalating further. In humans, touch may be even more important. Touch is the most highly developed sense at birth, far preceding language as a means of communication in human evolution. It’s surprising then that such a small amount of research has been conducted on touch relative to other senses in all of science and in the realm of emotion research in particular.

One of the primary functions of touch is to promote trust and cooperation. For example, teachers who touch students get them to volunteer more readily in classroom settings (Burgoon et al., 1996). As a second example, a touch on the arm by an experimenter led participants to give more money to an experiment partner—a sign of cooperative intent—compared to participants who were not touched (Kurzban, 2001). Touch also soothes in times of stress. For example, women showed decreased threat-related brain activation while anticipating a shock delivered from an experimenter when holding the hand of a spouse versus holding the hand of a stranger (Coan et al., 2006). In addition, infants who are touched by their caregivers respond more resiliently to uncomfortable medical procedures (Gray et al., 2002). Together, these results suggest that touch might be important for group processes. Specifically, touch within groups may enhance cooperation in team settings.

Dacher Keltner, Cassy Huang and I decided to test this hypothesis with respect to basketball teams. Basketball is a game where teams thrive on cooperation. Defensively, teams that work together can overcome individual deficiencies. Offensively, teams that work together will share the ball more, and will take (and make) easier shots as a result. The great Duke basketball coach, Mike Kryzyzweski, said it best: “A basketball team is like the five fingers on your hand. If you can get them all together, you have a fist. That’s how I want you to play.”

Given the importance of cooperation in basketball, we set out to try to understand whether we could determine how well teams cooperate with each other just by watching recorded basketball games. In particular, we wondered if observable behaviors during games would signal the levels of trust and cooperation endemic to each team, and whether this signal would predict actual wins and losses during the season. Based on the above analysis, we reasoned that physical touch was likely to be the best signal of cooperation in these team settings.

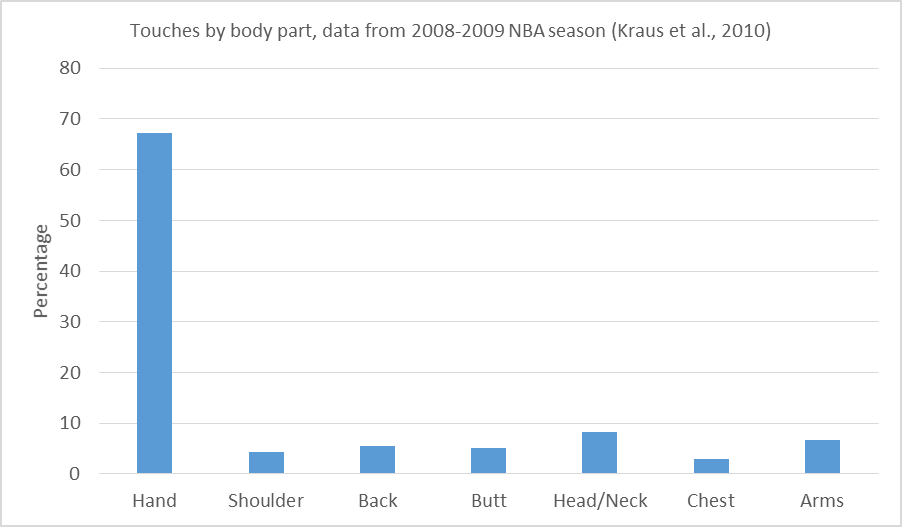

Knowing this background, we (actually Cassy) painstakingly watched recorded basketball games during the 2008-2009 professional basketball season, cataloguing the duration of every high five, butt slap, and chest bump that players laid on their teammates.

ABC Breaking News | Latest News Videos

We only watched games during the first month of the season, and restricted our analysis to games that were competitive (the final score separated the two teams by 9 points or less).

We expected that teams who touched more would win more across the entire season, and that is precisely what we found. Teams like the Lakers and Celtics who touched the most, also tended to perform the best over the course of the entire season, and in the games immediately following the game coded for touch. Moreover, this effect occurred even when we statistically accounted for how well teams performed during game coded for touch, preseason expectations for the performance of each team reported by basketball experts, and team salaries (Kraus, Huang, & Keltner, 2010). From these data, we reasoned that touch is an important indicator of teammates’ cooperation with each other, and is therefore an important barometer of success in a cooperation-based game like basketball. More broadly, emotion expressions communicated through touch can be a means for diagnosing the health of relationships within a group of individuals.

Figure 1: The chart shows the proportion each body part was touched during the course of NBA games during the 2008-2009 NBA season. Hand-to-hand touches were by far the most common followed by head/neck and arm touches.

Emotions Communicate Dominance and Affiliation

When I was in graduate school I had a brush with road rage. I had inadvertently cut off another driver and, in retaliation, that driver responded with dangerous and erratic driving behavior of his own. When we stopped at the next intersection, the driver appeared to want to escalate the confrontation into something more physical. My first reaction was to smile. It felt strange and out of place, but there I was grinning at a man who was willing to challenge me to a fist fight. Thinking back on this event, I realize that my impulse to smile may have helped deescalate the confrontation by signaling to the other driver that I had no intention of being aggressive.

This anecdote is indicative of a larger program of research that I have conducted about how people navigate the ambiguity of social interactions. It turns out that emotional displays provide us with a sensible roadmap or a set of heuristic responses that allow individuals to learn a great deal about interaction partners prior to any actual deliberate information exchange. In this sense, emotions provide windows into our intentions, motives, and competencies well before we have had a chance to provide that information intentionally.

My road rage confrontation inspired a new research program. In collaboration with my colleague Teh-way David Chen, I started examining professional fighters at the ritual weighing ceremony held one day prior to the fight. The ceremony is traditionally used by the betting public to size up the contenders and determine which fighter they believe will win the bout. We examined posed photographs from this ceremony when the two fighters engage in a face-off—staring directly at each other. We coded zygomatic major activity, which is the major muscle group that controls the lip curl of the smile.

Our findings aligned with the road rage anecdote: fighters who smiled more tended to lose more in the fight following the weighing ceremony, tended to be punched and kicked more, and tended to lose more by submission or knock out rather than by decision. Moreover, the smile coding predicted fight outcomes over and above estimates based on betting odds set by experts on fight gambling—even when controlling for betting odds predicting the likelihood of a win for each fighter, smiles predicted performance in the contest (Kraus & Chen, 2013). We interpreted these results to indicate that despite the demonstrable toughness and grit of each fighter, smiling fighters standing across from a dominant opponent were conveying their lack of enthusiasm for escalating the confrontation further.

Building on this initial work we have subsequently examined how expressions of pride communicate a person’s support for meritocratic beliefs. Prior research indicates that pride signals socially valued success, and because of its success-signaling function—pride may be an expression of not only achievement, but also of one’s values about achievement. That is, people who tend to express pride might be also implicitly acknowledging that their achievements are based on merit. Consistent with this view, people who tend to feel more pride in their everyday lives also tend to believe that society is more meritocratic and observers who perceive proud, versus joyful, expressions in lab settings believe that the expressers of pride tend to support meritocracy (Horberg, Kraus, & Keltner, 2013).

Empathic Processes and Social Hierarchy

I currently teach MBAs at the school of management at Yale University, and in my course called Power and Politics we are obsessed with empathic processes. Our obsession stems from the realization that in business exchanges it is vital to understand what others are feeling before we can know what they want. The problem of figuring out what people feel becomes more complex in the context of social hierarchies. Specifically, as space opens between people on the social ladder, the chances for misunderstanding increase. My final line of research on emotion and social hierarchy aims to understand empathic processes across status divides.

Much of my earlier research was based on an examination of how hierarchy shifts our attention to other people’s mental states. As we rise in social and economic status, we tend to focus on the self more (Kraus et al., 2012). This means focusing proportionately less on other people’s mental states on average, and applying our other-directed attention only to the most meaningful exchanges. This attentional focus might be driven by a need to perform more complex mental tasks while safeguarding our current resources from others. Whatever the cause, one result of this lack of attention to others is reduced empathic accuracy. Conversely, as you move down social and economic hierarchies your need to understand other people intensifies—you must be aware of the threats and opportunities in your environment, because a lack of awareness could negatively impact your life outcomes.

In a series of studies, we found that those higher in social class measured in terms of income, education, and self-perceived position in society tend to report lower levels of empathic accuracy in social interactions with strangers and on standard tests of empathic accuracy relying on accurately recognizing emotions in posed facial expressions relative to their lower social class counterparts (Kraus, Cote, & Keltner, 2010). In related work, we found this same pattern among pairs of friends. High social class friends were good at perceiving their friend’s positive emotions, but impaired in their ability to recognize hostile emotions (anger, contempt, disgust). In contrast, lower social class friends were equally good at accurately perceiving their friend’s positive and negative affective states (Kraus, Horberg, Goetz, & Keltner, 2011). This body of research suggests that, as people rise in social class, their attention to others’ mental states diminishes.

There are several potential consequences of reduced empathic processes among high social class individuals. Perhaps the most alarming of these consequences is the compassion divide that results. Compassion is defined simply as caring about the suffering of others and it is a main emotional motivator of prosocial behavior. One problem with persistently reduced empathic accuracy is that high social class individuals might not care as much about the suffering of others. In effect, high social class individuals may pick up less of the cues of suffering expressed by others, and experience less compassion as a result. In contrast, those lower in social class who attend to others’ emotional processes may respond more readily to others’ suffering.

In collaboration with Jennifer Stellar of the University of Toronto and Vida Manzo of Northwestern University, we exposed high and low social class participants to a video showing children suffering with cancer and a neutral instructional video in counterbalanced order. We found that high social class participants had reduced changes in heart rate and self-reported compassion responses to the suffering video than did the lower social class participants (Stellar, Manzo, Kraus, & Keltner, 2012). These data suggest that high social class individuals responded less to the suffering of cancer patients than did their lower-class counterparts.

Lack of understanding of others’ intentions and mental states also has direct consequences for compassionate behaviors, specifically helping others. For instance, in one series of studies we found that higher social class participants gave less in a dictator game or trust game to an anonymous partner online than did their lower social class counterparts—a finding mirroring the compassion results reported above (Piff, Kraus, Cote, Cheng, & Keltner, 2010). Reduced understanding of others’ mental states might also mean more callous judgments of society and intergroup resource sharing more broadly.

In this realm, we have found for instance that individuals higher in social class tend to see societal inequality as caused by the hard work and superior talent of successful people, whereas lower class individuals tend to see it as caused by structural advantages and disadvantages (Kraus, Piff, & Keltner, 2009). Relatedly, we also found that higher social class individuals are more likely to think of social class differences as caused by genetic superiority or inferiority than their lower class counterparts (Kraus & Keltner, 2013).

But our findings are not all doom and gloom for cooperation and resource sharing among societal elites. In other experimental work, we found that showing a compassion-inducing video of suffering before an experiment makes high income participants just as helpful as low income ones—ostensibly because suffering cues attention to the possibility that others may need help (Piff, Kraus, et al., 2010). These results suggest that high social class individuals have the capacity to be prosocial when motivated properly. Follow up work shows more of the same—when reputation is involved, high social class participants tend to give more than lower social class participants (Kraus & Callaghan, 2016).

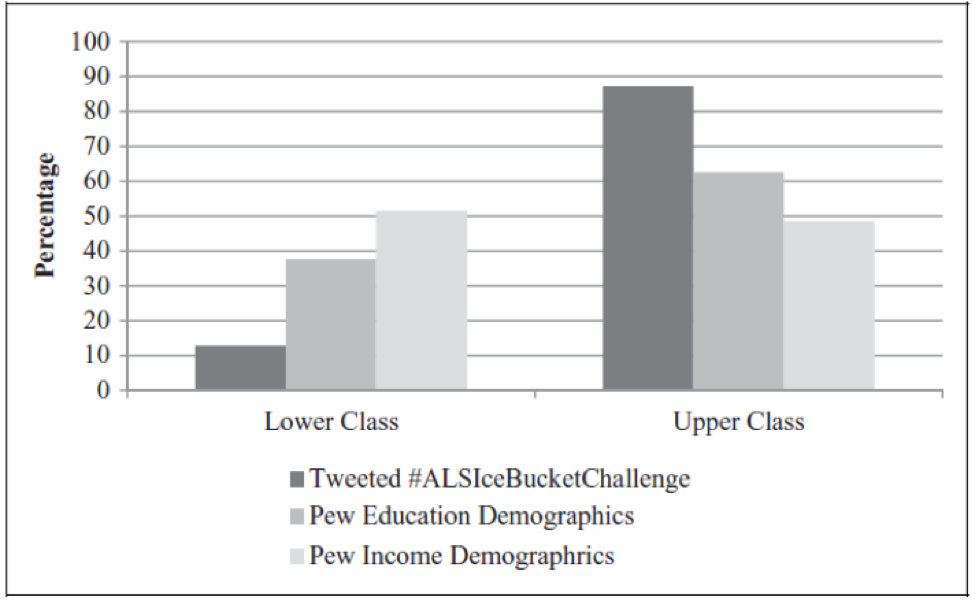

For instance, on a visible social media campaign like the Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) ice bucket challenge, higher social class participants were more likely to participate on twitter by sending messages about ALS than were their lower social class counterparts. We also found that patterns of cooperation and defection are quite malleable in our experiments. For instance, putting people in upper class clothing (i.e., a business suit) increased competitive behaviors in a negotiation and reduced cooperation relative to neutral clothing, regardless of the social class of the participant (Kraus & Mendes, 2014). This shows that people higher in social class are not, by their nature, unable to focus on others.

Overall, there is much to be learned about how empathic processes can be shaped to allow individuals with more resources to connect with those around them who might be in need. Darwin’s words ring true with respect to this research program: “Sympathy… will have been increased through natural selection, for those communities with the greatest number of sympathetic members will flourish best and rear the greatest number of offspring.” (Darwin, 1877/1998).

References

Burgoon, J. K., Buller, D. B., Woodall, W. G. (1996). Nonverbal communication: the unspoken dialogue. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Coan, J. A., Schaefer, H. S., & Davidson, R. J. (2006). Lending a hand: Social regulation of the neural response to threat. Psychological Science, 17, 1032–1039.

Darwin, C., Ekman, P., & Prodger, P. (1998). The expression of the emotions in man and animals. Oxford University Press, USA.

Gray, L., Miller, L. W., Philipp, B. L., & Blass, E. M. (2002). Breastfeeding is analgesic in healthy newborns. Pediatrics, 109, 590–593.

Horberg, E. J., Kraus, M. W., & Keltner, D. (2013). Pride displays communicate self-interest and support for meritocracy, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 105, 24-37.

Kraus, M. W. & Callaghan, B. (2016). Social class and pro-social behavior: The moderating role of public versus private contexts. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 7, 769-777.

Kraus, M. W., & Chen, T. D. (2013). A winning smile? Smile intensity, physical dominance, and fighter performance, Emotion, 13, 270-290.

Kraus, M. W., Côté, S., & Keltner, D. (2010). Social class, contextualism, and empathic accuracy, Psychological Science, 21, 1716-1723.

Kraus, M. W., Horberg, E. J., Goetz, J. L., & Keltner, D. (2011). Social class rank, threat vigilance, and hostile reactivity, Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 37, 1376-1388.

Kraus, M. W., Huang, C., & Keltner, D. (2010). Tactile communication, cooperation, and performance: An ethological study of the NBA, Emotion, 10, 745-749.

Kraus, M. W., & Keltner, D. (2013). Social class rank, essentialism, and punitive judgment, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 105, 247-261.

Kraus, M. W., & Mendes, W. B. (2014). Sartorial symbols of social class elicit class-consistent behavioral and physiological responses: A dyadic approach. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 143(6), 2330-2340.

Kraus, M. W., Piff, P. K., Mendoza-Denton, R., Rheinschmidt, M. L., & Keltner, D. (2012). Social class, solipsism, and contextualism: How the rich are different from the poor. Psychological Review, 119, 546–572.

Kraus, M. W., Piff, P. K., & Keltner, D. (2009). Social class, sense of control, and social explanation, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97, 992-1004.

Kurzban, R. (2001). The social psychophysics of cooperation: Nonverbal communication in a public goods game. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 25(4), 241-259.

Piff, P. K., Kraus, M. W., Côté, S., Cheng, B., & Keltner, D. (2010). Having less, giving more: The influence of social class on prosocial behavior, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 99, 771-784.

Stellar, J., Manzo, V., Kraus, M. W., & Keltner, D. (2012). Class and compassion: Socioeconomic factors predict responses to suffering, Emotion, 12, 449-459.