Assessing and Understanding the Role of Everyday Emotion and Affect in Relation to Stress and Health

Joshua M. Smyth+, Department of Biobehavioral Health, The Pennsylvania State University, USA; jms1187@psu.edu

Andreas B. Neubauer+, German Institute for International Educational Research (DIPF), Frankfurt am Main, Germany; Center for Research on Individual Development and Adaptive Education of Children at Risk (IDeA), Frankfurt am Main, Germany; andreas.neubauer@psychologie.uni-heidelberg.de

Michael A. Russell+, Department of Biobehavioral Health, The Pennsylvania State University, USA; mar60@psu.edu

+All authors contributed equally to this work

Introduction and Overview

Emotion and its connections with health-relevant processes (e.g., physiology, health behavior) and health outcomes have a long and rich history of study, both within and outside of psychology. Speaking very generally, this work has shown that broad characterizations of typical emotional states (e.g., negative and positive affect) as well as specific emotions or affects (e.g., anger) are both cross-sectionally and longitudinally related to health indicators (including self-reports of health, risk profiles, morbidity and mortality). Although there exists a great diversity of research methodologies in the study of emotion and health, much of the work has relied on either large-scale, naturalistic panel or retrospective survey designs or tightly controlled experimental work. Each of these approaches has tremendous utility; notably, the former offers good characterization of relationships at the between-person level and the latter offers high control and often excellent characterization of temporal and causal processes over short periods of time (e.g., minutes to hours). There is now a growing interest in supplementing these approaches with methodologies that allow the capture of emotion-related processes and outcomes in everyday life, often over days or weeks. Ecological Momentary Assessment [EMA] is increasingly utilized in emotion and health research, often with a focus on within-person dynamics of affective states and their relationship to health relevant processes (e.g., physiology, health behaviors, interpersonal processes) in people’s everyday lives. In this article, we present what we see as some key opportunities for applying EMA and related methods to emotion and affect science as related to health.

EMA, and related approaches such as experience sampling, daily diary approaches, and others, fall under the broad umbrella of ambulatory assessment, a wide range of methods allowing the study of individuals in their naturalistic environments (Smyth et al., 2017). For simplicity, we will use the term EMA broadly throughout this article, although most of our discussion is relevant to other approaches as well. The general category of ambulatory assessment subsumes a range of reporting strategies, including self-report, observational, and (often wearable) biological or physiological sensors (Trull & Ebner-Priemer, 2013). Although not specifically communicated in the name, EMA typically refers to ambulatory assessment strategies that feature self-reports. The defining feature of the EMA method is the collection of (more-or-less) momentary self-reports, multiple times per day, in a person’s everyday, naturalistic context. Such an assessment strategy allows researchers to track shifts in context, affect/mood, and behavior across multiple time scales (across hours, days, weeks) and determine the degree to which shifts in one (i.e., context) are associated with shifts in the other (i.e., affect and behavior). Although there is great interest in this method as of late, the EMA approach is not new – self-monitoring, thought-sampling, and time use reports have been used since the 1800s if not earlier, and more formal variants of experience sampling have existed since the 1970s (see Larson & Csikszentmihalyi, 1983). Over the decades, the specifics of the approaches have varied with the available tools and technologies; early work used manual recording (e.g., paper-and-pencil diaries), then adding technologies over time such as personal paging devices, “smart” wristwatches, and personal digital assistants, and now sophisticated EMA implementations using portable tablets and smartphones.

EMA offers some notable features for the study of emotions in everyday life; we see these as advantages/strengths of EMA, although of course their relevance and utility depend upon the purpose of study. There are many comprehensive reviews and chapters that outline the potential benefits of EMA in general (e.g., see Shiffman, Stone, & Hufford, 2008; Smyth et al., 2017; Trull & Ebner-Priemer, 2013), so we will not duplicate those arguments here. Rather, we focus on a few features of EMA approaches, and the resultant data one obtains, that seem of particular importance and interest for researchers interested in emotional states, emotional processes, and health. Namely, the opportunity to study emotional processes as they unfold in natural settings in everyday life (i.e., ecological validity, broadly defined) and the capacity to collect repeated observations from the same individuals over time and across varying contexts and situations (i.e., the capacity to capture data on – and model appropriately – both between- and within-person parameters, including time/temporal processes). We then outline several important opportunities and challenges regarding the use of EMA for emotion-health research that we hope will help inspire future research.

Ecological Validity – Why Extend Beyond Survey Research and the Lab?

Repeated assessments of affective states in people’s natural environments offer unique advantages for investigating the interrelation of affective processes and health related outcomes. Compared to more traditional “single-shot” cross-sectional questionnaire assessments, by assessing affective states in the moment, the impact of memory processes can be minimized with EMA (Schwarz, 2012). Whereas in cross-sectional studies participants are often instructed to remember how they felt over a certain time frame (e.g., “How angry did you feel in the last four weeks?”) or during a certain event (e.g., “How happy did you feel when X happened?”), affective states in EMA are assessed at the moment (e.g., “How sad do you feel right now?”), circumventing memory retrieval processes in rendering the response to the respective question. According to the accessibility model of emotional self-report (Robinson & Clore, 2012), momentary ratings do not require episodic or semantic memory processes, contrary to retrospective assessments; therefore, momentary assessments differ qualitatively from retrospective assessments. Conner and Barrett (2012) proposed that because of these differences, momentary and retrospective ratings might capture different contributions of the “experiencing self” versus the “remembering / believing self”, respectively. They further argue that momentary ratings (the experiencing self) are more tightly related to physiological measures, whereas retrospective ratings (the remembering / believing self) are more predictive of deliberate decisions and future behavior. Hence, according to this view, neither of these assessment types is per se “better”, but their validity depends on the criterion used.

There is some preliminary support for this prediction: For example, Joseph, Kamarck, Muldoon, and Manuck (2014) reported results showing that quality of marital interactions assessed via EMA (assessed over four day) was associated with carotid artery intima medial thickness (IMT), a marker of atherosclerosis and risk factor for future heart attack and stroke. In contrast, global assessments of marital quality were unrelated to IMT, demonstrating superior validity for momentary ratings in the prediction of physiological markers. Global retrospective assessments, on the other hand, often outperform momentary assessments in their predictive validity of deliberate choices. For example, in a study by Wirtz, Kruger, Napa Scollon, and Diener (2003), retrospective ratings of the perceived pleasure of a vacation were associated with the desire to repeat the vacation, whereas (aggregated) momentary ratings collected during the vacation were not. In other words, the way the vacation was remembered was more important for the intention to repeat the experience than the way the vacation was experienced in vivo. In the context of health relevant behavior, Redelmeier, Katz, and Kahneman (2003) reported data on the differential predictive validity for return rates for a follow-up colonoscopy. In this study, participants reported momentary pain ratings several times during a colonoscopy and provided retrospective pain ratings after the procedure. The amount of pain remembered after a colonoscopy (but not the average pain reported during the colonoscopy) predicted whether or not participants returned for a follow-up procedure. Future research is needed to better understand when and under which conditions momentary ratings and retrospective ratings diverge in their predictive validity for health related outcomes. The research presented here emphasizes that EMA offers unique potential in this regard above and beyond classical survey research.

EMA also offers added value compared to laboratory-based, experimental studies. The latter are considered (often rightfully so) the gold-standard for establishing causal relationships among variables of interest. However, this high internal validity often comes at the cost of low ecological validity. Notably, it is often difficult or impossible to replicate many aspects of everyday life in a laboratory. At the same time, contexts that are created for laboratory research are often artificial in that they do not resemble situations that study participants are confronted with in their daily lives. For example, one of the most often applied procedures to induce stress in a laboratory setting, the Trier Social Stress Test (TSST; Kirschbaum, Pirke, & Hellmammer, 1993), consists of a mock job interview. In this procedure, the interviewers wear lab coats and are instructed to show a neutral facial expression throughout the interview. This situation is arguably artificial in that most individuals will not encounter interviewers who are completely emotionally distant in their daily lives. Experimental procedures such as the TSST have proven very fruitful in prior research and they have generated a large body of vastly important knowledge about the stress response. Nevertheless, future research needs to address the question whether and to what extent the processes uncovered in the laboratory also operate in individuals’ daily lives.

Why Within-Person Variability is Important

Human thoughts, feelings, and behaviors are complex phenomena. Their interplay forms a complex dynamical system, for whom many of its defining characteristics are constantly in flux – not only across years, but even across situations, and in the case of affect across moments (Nesselroade & Ram, 2004). The basic tenet of EMA research is that such variability is not solely “error”, as was implied by traditional psychometric models (most famously Cronbach & Furby, 1970), but is meaningful variability that represents fluctuations in response to changing environments, interpersonal interactions, and psychobiological states. In fact, contingencies between situations, affect, and behavior have formed the basis of important theoretical developments in personality and health psychology (e.g., Fleeson, 2004; Mischel & Shoda, 1995; Sliwinski, Almeida, Smyth, & Stawski, 2009). When viewed in this way, within-person variability in affect forms the basis of important individual differences (dynamic characteristics; e.g., Ram & Gerstorf, 2009) at the between-person level that may be informative for health and well-being over and above a person’s “average” level of affect (Schneider & Stone, 2015).

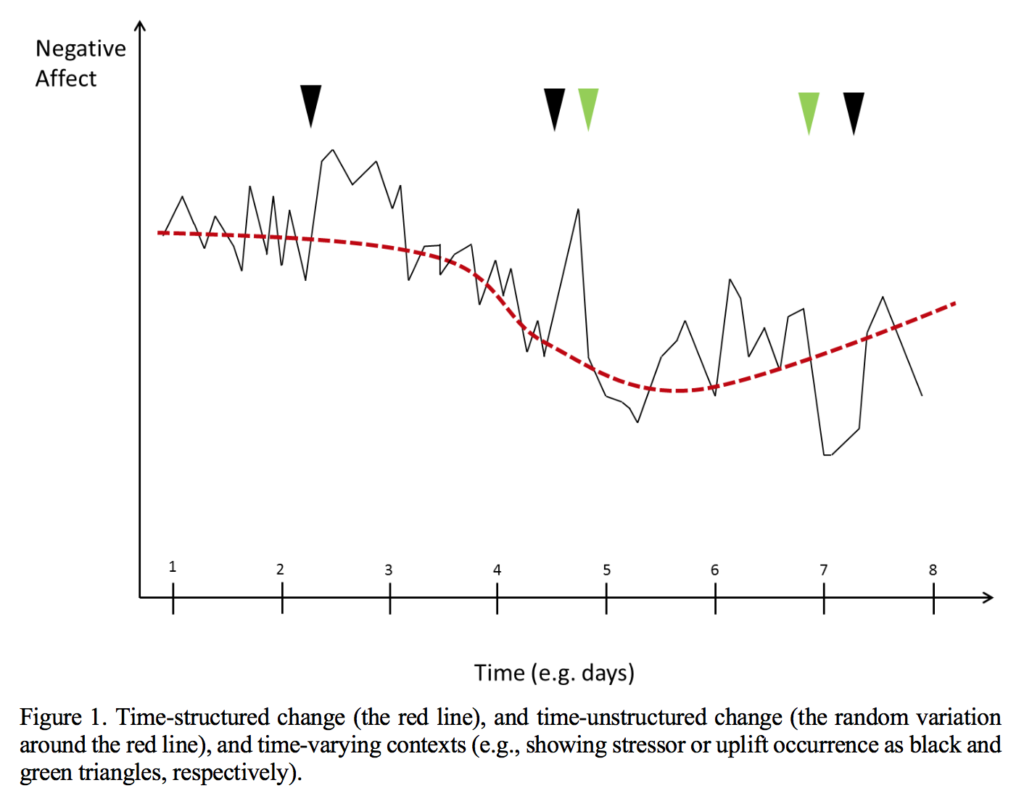

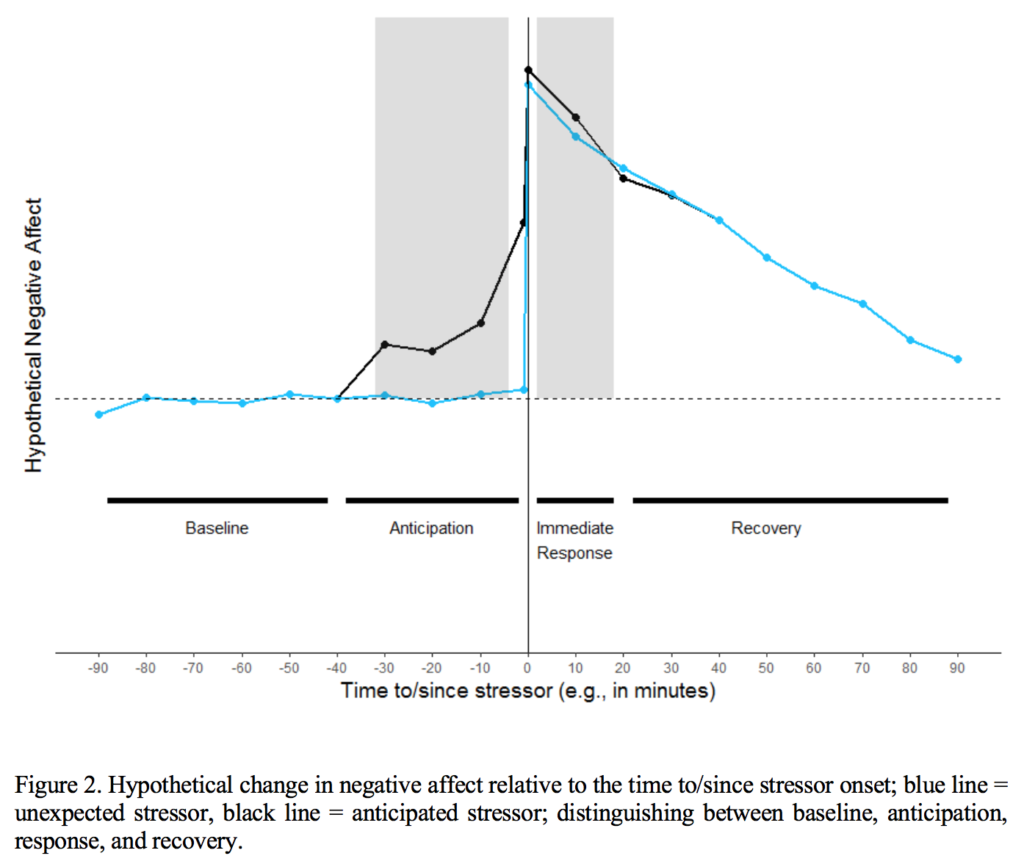

Within-person (or intraindividual) variability has often been conceptually organized into two broad varieties (see Ram & Gerstorf, 2009): (1) time-structured, which consists of change that is organized with respect to time (e.g., diurnal curves) and which may show egress from a central value (e.g., a baseline or homeostatic mean value) and (2) unstructured or “reversible” change, which represents a departure or “blip” that eventually returns to a homeostatic value (e.g., the mean) and represents a temporary shift from a point of stability; examples of such change may be spikes in negative affect around a person’s mean level or around their diurnal curve (see Figure 1), often in response to external events (be they negative or positive). From a practical standpoint, time-structured change in affect can be captured using random growth curve modeling techniques that estimate a trajectory across a specific time frame (e.g., a day) and allow the trajectory parameters to be different for each individual. Such temporal patterns represent an important source of time-structured variability, and the repeated, intensive measurement employed in EMA studies allows the examination of such change across a wide range of resolutions. For example, one may be interested in elucidating the trajectories of specific moods throughout a typical day (e.g., Stone, Smyth, Pickering, & Schwartz, 1996) or how affect changes by day of the week (Larson & Richards, 1998). One may also be interested in affective trajectories leading up to and out of a particular event of interest, such as a binge eating episode (Smyth et al., 2007) or the occurrence of a stressful event (Neubauer, Smyth, & Sliwinski, 2018; Neupert, Neubauer, Scott, Hyun, & Sliwinski, 2018; Scott, Ram, Smyth, Almeida, & Sliwinski, 2017). Given the temporal density of measurement, analysts may choose to hypothesize the shape of the trajectory a priori (linear, quadratic, cubic) or use complex curve fitting techniques that provide a data-driven solution such as LOESS curves or time-varying effect modeling (Li, Root, & Shiffman, 2006; Mason, Zaharakis, Russell, & Childress, 2018; Shiffman, 2014).

Unstructured or reversible changes in affect can be captured via difference scores from a baseline value (the person’s mean or the immediately previous score), which can be aggregated into variability parameters at the between-person level such as the intraindividual standard deviation (iSD), which captures each person’s typical absolute difference in affect from their own mean level; or the mean of successive squared differences (MSSD), which captures each person’s typical affective shift, or the typical difference between their current and immediately previous affect level. These between-person differences in within-person dynamics can be estimated and used in the prediction of health outcomes. For example, affective instability, an indicator of time-structured within-person variability characterized by bigger moment-to-moment shifts in affect on average in some individuals versus others, has been discussed as a key pathway through which daily experiences are thought to impact psychological and physical health (John & Gross, 2004; Patel et al., 2015) and appears to be a differentiating characteristic of individuals with borderline personality disorder versus major depression (Trull et al., 2008).

EMA studies have also drilled into the momentary space to examine affective fluctuations and their relationship to physical health in the moment, as well as how they relate to the characteristics of individuals and the situations experienced in everyday life. For example, Russell, Smith, and Smyth (2015) found that experiences of anger in day-to-day life were associated with increases in symptom severity in a sample of patients diagnosed with asthma or rheumatoid arthritis. The associations were stronger based on anger regulation style and sex, with men who showed high levels of anger suppression showing the greatest anger-related symptom increases. In this same sample, Smyth, Zawadzki, Santuzzi, and Filipkowski (2014) showed that patients experienced worse mood and more severe symptoms when experiencing stress in their day-to-day lives, but this association was attenuated among those who reported having strong social support. Increasingly, recent work also integrates ambulatory physiological measures with EMA data capture. Zawadzki, Mendiola, Walle, and Gerin (2016) showed that affective valence and arousal measured via EMA in day-to-day life were differentially associated with ambulatory blood pressure measured using a monitoring cuff that individuals wore as they went through their everyday lives. Such investigations highlight the unique roles of affective dimensions in contributing to health and well-being and may have important implications for interventions (e.g., to guide ecological momentary interventions and/or just-in-time treatment; Heron & Smyth, 2010; Smyth & Heron, 2016).

Time-varying Contexts

As alluded to above, affective dynamics can be understood as complex phenomena that are at least partly influenced by fluctuations in the environment. In the realm of affect-health associations, contextual variables such as the occurrence of minor stressors in daily life (also referred to as daily hassles) have received a substantial amount of attention in recent years. Research has generally shown that within-person fluctuations in the presence of such stressors are negatively related to within-person fluctuations in affective well-being (e.g., Almeida, 2002; Bolger, DeLongis, Kessler, & Schilling, 1989): That is, at occasions when an individual reports more stressors than they typically report, affective well-being is lower than their average, a phenomenon that has often been termed affective reactivity or stress reactivity. Although the use of the term “reactivity” is somewhat of a misnomer given that it is typically operationalized using a concurrent (not temporally sequenced) association between stressors and affect in daily diary studies, it has nonetheless shown itself to be of utility, emerging as a predictor of both mental and physical health outcomes including anxiety and depressive disorders (Charles, Piazza, Mogle, Sliwinski, & Almeida, 2013), chronic disease (Piazza, Charles, Sliwinski, Mogle, & Almeida, 2013), and mortality (Mroczek et al., 2015).

Challenges and Future Directions

Although highly selective, our previous elaborations demonstrate the potential and promises of EMA for investigating the relevance of affect levels and affective dynamics for health-related outcomes. In this section, we briefly sketch out some of the current developments, opportunities, and challenges in this field.

One current trend in EMA is an increasing application of physiological measurements to capture variables related to affective experiences, such as arousal of the sympathetic nervous system (e.g., via ambulatory monitoring of skin conductance) or activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis (via saliva samples collected in individuals’ daily lives). These approaches yield some promise because they allow for capturing additional information beyond self-reports and can therefore be an important way to supplement findings relying on self-reports only. However, these methods sometimes put larger burden on study participants (e.g., repeated saliva samples in daily life), can be cost intensive, and require additional technical and methodological expertise on researchers’ side. Furthermore, studies validating the assessment of highly sensitive physiological indicators (such as skin conductance reactivity) outside of controlled laboratory settings are scarce. Therefore, we think that it is unlikely that these measures will be able to replace self-reports of affective states in the near future, but they can provide important additional information when used concurrently with momentary self-report assessments.

Another current issue in EMA is the utilization of passive sensors (e.g., GPS sensors or accelerometers) built into smartphones. Information from these sensors can be used to monitor participants’ current context. This information can be used in (at least) two important ways. First, passive sensor data can supplement self-report information of time-varying contexts. In many applications, information on participants’ current context is obtained via self-report from the participants (e.g., “Are you currently in the presence of other people?”; “How physically active were you today?”). Hence, context in studies that rely exclusively on self-reports needs to be understood as perceived context. Information from passive sensors can add information on context that goes beyond individuals’ perception. Second, information from sensor data can be used to trigger questionnaires at appropriate moments. For example, if a researcher is interested in the question if physical activity attenuates the effect of mood on pain symptoms in a patient population, she might consider triggering the assessment of mood and pain specifically in situations after an accelerometer has detected high or low physical activity. Broadly, we see tremendous opportunities for adaptive (or “just-in-time”) assessment to be developed and implemented.

Finally, there are current methodological developments that can help further our understanding of the complex time-dynamics of affective experiences in daily life. As mentioned previously, individual differences in stress-affect couplings have emerged as consistent predictors of mental and physical health outcomes even years later (Charles et al., 2013; Mroczek et al., 2015; Piazza et al., 2013). However, a number of current challenges related to this approach need to be tackled in further research.

Conclusions

EMA represents a powerful approach for the study of affect levels, dynamics, and their interrelation to both temporally proximal and distal indicators of health and well-being in everyday life. The EMA approach is particularly suited to the study of affective processes that unfold over a relatively short time scale and are responsive to the situations and environments that people encounter in their everyday lives. More broadly, these approaches allow innovative and potentially fruitful methods for characterizing processes of relevance to emotion regulation. Although EMA is not a new field, and great contributions have been made using these methods, we believe that its potential utility can be enhanced with regard to understanding the interplay amongst naturalistic affective, stress, and health processes. In particular, we believe that there are many exciting new developments in the assessment, characterization, and statistical analysis of within-person emotional dynamics and the between-person differences in these dynamics that may be informative for distal health outcomes. Much work remains in order to more precisely determine the strengths and limitations of the EMA approach for the discovery of affect-health contingencies, but we are enthusiastic about the promise of the EMA approach for contributing important information about how emotional and physical well-being intertwine through people’s everyday experiences – from moment to moment and from day to day – and how this interplay may enrich our understanding of health and disease processes during key points in the lifespan.

References

Bolger, N., DeLongis, A., Kessler, R. C., & Schilling, E. A. (1989). Effects of daily stress on negative mood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 808 – 818. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.57.5.808

Charles, S. T., Piazza, J. R., Mogle, J., Sliwinski, M. J., & Almeida, D. M. (2013). The Wear and Tear of Daily Stressors on Mental Health. Psychological Science, 24, 733-741. doi:10.1177/0956797612462222

Cronbach, L. J., & Furby, L. (1970). How we should measure” change”: Or should we? Psychological Bulletin, 74, 68.

De Boor, C. (1972). On calculating with B-splines. Journal of Approximation theory, 6, 50-62.

Fleeson, W. (2004). Moving personality beyond the person-situation debate – The challenge and the opportunity of within-person variability. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 13, 83-87. doi:10.1111/j.0963-7214.2004.00280.x

Hastie, T., & Tibshirani, R. (1993). Varying-coefficient models. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series B (Methodological), 757-796.

Heron, K., & Smyth, J. (2010). Ecological Momentary Interventions: Incorporating mobile technology into psychosocial and health behavior treatments. British Journal of Health Psychology, 15, 1-39.

John, O. P., & Gross, J. J. (2004). Healthy and unhealthy emotion regulation: Personality processes, individual differences, and life span development. Journal of personality, 72, 1301-1334.

Laird, N. M., & Ware, J. H. (1982). Random-effects models for longitudinal data. Biometrics, 963-974.

Larson, R., & Richards, M. (1998). Waiting for the weekend: Friday and Saturday night as the emotional climax of the week. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 82, 37-51.

Li, R., Root, T. R., & Shiffman, S. (2006). A local linear estimation procedure for functional multilevel modeling. In T. A. Walls & J. L. Schafer (Eds.), Models for intensive longitudinal data (pp. 63-83). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Mason, M. J., Zaharakis, N. M., Russell, M., & Childress, V. (2018). A pilot trial of text-delivered peer network counseling to treat young adults with cannabis use disorder. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment.

Mischel, W., & Shoda, Y. (1995). A cognitive-affective system-theory of personality: Reconceptualizing situations, dispositions, dynamics, and invariance in personality structure. Psychological Review, 102, 246-268. doi:10.1037/0033-295x.102.2.246

Mroczek, D. K., Stawski, R. S., Turiano, N. A., Chan, W., Almeida, D. M., Neupert, S. D., & Spiro, A. (2015). Emotional reactivity and mortality: Longitudinal findings from the VA Normative Aging Study. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 70, 398-406.

Neubauer, A. B., Smyth, J. M., & Sliwinski, M. J. (2018). When you see it coming: Stressor anticipation modulates stress effects on negative affect. Emotion, 18, 342–354. doi:10.1037/emo0000381

Neubauer, A. B., Voelkle, M. C., Voss, A., & Mertens, U. K. (in press). Estimating reliability of within-person couplings in a multilevel framework. Journal of Personality Assessment. doi: 10.1080/00223891.2018.1521418

Neupert, S. D., Neubauer, A. B., Scott, S. B., Hyun, J., & Sliwinski, M. J. (2018). Back to the future: Examining age differences in processes before stressor exposure. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gby074

Nesselroade, J. R., & Ram, N. (2004). Studying intraindividual variability: What we have learned that will help us understand lives in context. Research in Human Development, 1, 9-29.

Patel, R., Lloyd, T., Jackson, R., Ball, M., Shetty, H., Broadbent, M., . . . Taylor, M. (2015). Mood instability is a common feature of mental health disorders and is associated with poor clinical outcomes. BMJ open, 5, e007504.

Piazza, J. R., Charles, S. T., Sliwinski, M. J., Mogle, J., & Almeida, D. M. (2013). Affective reactivity to daily stressors and long-term risk of reporting a chronic physical health condition. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 45, 110-120.

Ram, N., & Gerstorf, D. (2009). Time-Structured and Net Intraindividual Variability: Tools for Examining the Development of Dynamic Characteristics and Processes. Psychology and Aging, 24, 778-791. doi:10.1037/a0017915

Russell, M. A., Smith, T. W., & Smyth, J. M. (2015). Anger expression, momentary anger, and symptom severity in patients with chronic disease. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 50, 259-271.

Schneider, S., & Stone, A. A. (2015). Ambulatory and diary methods can facilitate the measurement of patient-reported outcomes. Quality of Life Research, 1-10.

Scott, S. B., Ram, N., Smyth, J. M., Almeida, D. M., & Sliwinski, M. J. (2017). Age differences in negative emotional responses to daily stressors depend on time since event. Developmental Psychology, 53, 177–190. doi:10.1037/dev0000257

Shadish, W. R., Zuur, A. F., & Sullivan, K. J. (2014). Using generalized additive (mixed) models to analyze single case designs. Journal of school psychology, 52, 149-178.

Shiffman, S. (2014). Conceptualizing analyses of ecological momentary assessment data. nicotine & tobacco Research, 16(Suppl 2), S76-S87.

Singer, J. D., & Willett, J. B. (2003). Applied Longitudinal Data Analysis: Modeling Change and Event Occurrence. New York: Oxford University Press.

Sliwinski, M. J., Almeida, D. M., Smyth, J., & Stawski, R. S. (2009). Intraindividual Change and Variability in Daily Stress Processes: Findings From Two Measurement-Burst Diary Studies. Psychology and Aging, 24, 828-840. doi:10.1037/a0017925

Smyth, J. & Heron, K. (2016). Is providing mobile interventions “just-in-time” helpful? An experimental proof of concept study of just-in-time intervention for stress management. Wireless Health, 89-95. doi: 10.1109/WH.2016.7764561

Smyth, J., Sliwinski, M., Zawadzki, M., Scott, S., Conroy, D., Lanza, S., Marcusson-Clavertz, D., Kim, J., Stawski, R., Stoney, C., Buxton, O., Sciamanna, C., Green, P., & Almeida, D. (2018). Everyday stress response targets in the science of behavior change. Behavior Research and Therapy, 101, 20-29.

Smyth, J. M., Wonderlich, S. A., Heron, K. E., Sliwinski, M. J., Crosby, R. D., Mitchell, J. E., & Engel, S. G. (2007). Daily and momentary mood and stress are associated with binge eating and vomiting in bulimia nervosa patients in the natural environment. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 75, 629.

Smyth, J. M., Zawadzki, M. J., Santuzzi, A. M., & Filipkowski, K. B. (2014). Examining the effects of perceived social support on momentary mood and symptom reports in asthma and arthritis patients. Psychology & Health, 29, 813-831.

Stone, A. A., Smyth, J. M., Pickering, T., & Schwartz, J. (1996). Daily mood variability: Form of diurnal patterns and determinants of diurnal patterns. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 26, 1286-1305.

Trull, T. J., & Ebner-Priemer, U. (2013). Ambulatory Assessment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 9, 151-176. doi:doi:10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185510

Trull, T. J., Solhan, M. B., Tragesser, S. L., Jahng, S., Wood, P. K., Piasecki, T. M., & Watson, D. (2008). Affective instability: measuring a core feature of borderline personality disorder with ecological momentary assessment. Journal of abnormal psychology, 117, 647.

Zawadzki, M. J., Mendiola, J., Walle, E. A., & Gerin, W. (2016). Between-person and within-person approaches to the prediction of ambulatory blood pressure: the role of affective valence and intensity. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 39, 757-766.