![Ainize[1]](http://emotionresearcher.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/Ainize1.jpg)

Moïra Mikolajczak, Research Institute for Psychological Sciences, Université catholique de Louvain & Ainize Peña-Sarrionandia, Psychology Department, University of the Basque Country

Moïra Mikolajczak, Research Institute for Psychological Sciences, Université catholique de Louvain & Ainize Peña-Sarrionandia, Psychology Department, University of the Basque Country

A Brief Primer on Measures of Emotional Intelligence

March 2015 – Although we all experience emotions, we markedly differ in the extent to which we identify, express, understand, regulate and use our own and others’ emotions. The concept of emotional intelligence (EI) has been proposed to account for this idea (Mayer & Salovey, 1997). Past debates on the status of EI have given birth to a tripartite model of EI (Mikolajczak, Petrides, Coumans, & Luminet, 2009).

Briefly, this model posits three levels of EI: knowledge, abilities and traits. The knowledge level refers to what people know about emotions and emotionally intelligent behaviors (e.g. Do I know which emotional expressions are constructive in a given social situation?). The ability level refers to the ability to apply this knowledge in a real-world situation (e.g., Am I able to express my emotions constructively in a given social situation?). The focus here is not on what people know but on what they can do: Even though many people know that they should not shout when angry, many are simply unable to contain themselves. The trait level refers to emotion-related dispositions, namely, the propensity to behave in a certain way in emotional situations (Do I typically express my emotions in a constructive manner in social situations?). The focus here is not on what people know or on what they are able to do, but on what they typically do over extensive periods of time in social situations. For instance, some individuals might be able to express their emotion constructively if explicitly asked to do so (so they have the ability), but they do not manage to manifest this ability reliably and spontaneously over time. These three levels of EC are loosely connected – declarative knowledge does not always translate into ability, which, in turn, does not always translate into usual behavior – and should therefore be assessed using different instruments.

Knowledge and abilities are essentially assessed using intelligence-like tests such as the MSCEIT (Mayer Salovey Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test; Mayer, Salovey & Caruso, 2002), the STEU (Situational Test of Emotional Understanding ; MacCann & Roberts, 2008) or the GERT (Geneva Emotion Recognition Test, Schleger, Grandjean & Scherer, 2013), while usual emotional behavior is assessed using personality-like questionnaires such as the TEIQUE (Trait Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire; Petrides, 2009), the EQ-I (Emotional Quotient Inventory (Bar-On, 2004) or, more recently, the PEC (Profile of Emotional Competence ; Brasseur, Grégoire, Bourdu & Mikolajczak, 2013).

The Importance of Trait EI

The literature indicates that the trait level of EI, on which we will focus in this paper, has a significant impact on four of the most important domains of life: well-being, health, relationships and work performance. We remain neutral here on whether measures of EI which are not trait-based have a comparable impact in any of these domains.

For instance, people with greater trait EI have enhanced well-being and mental health (for a recent meta-analysis, see Martins, Ramalho & Morin, 2010). They also have better physical health, as evidenced in a recent nationally representative study conducted by our team in collaboration with the largest mutual benefit society in Belgium (Mikolajczak et al., in press). Socially speaking, they seem to have more satisfying social and marital relationships (e.g. Schutte et al., 2001; see Malouff, Schutte, & Thorsteinsson, 2014 for a meta-analysis). Finally, a recent meta-analysis (O’Boyle et al., 2011) shed light on the debate on EI and job performance: although not all studies found a significant relationship, the aggregate effect confirms that people with higher trait EI do achieve superior job performance.

It is noteworthy that despite early fears that trait EI would not predict additional variance in the above-mentioned outcomes beyond the big five personality factors and intelligence, the vast majority of studies actually refute this fear (see Andrei, Siegling, Baldaro & Petrides, under review, and O’Boyle et al., 2011 for meta-analyses confirming the incremental validity of trait EI regarding health and job performance, respectively).

Improving Trait EI: Data and Recommendations

Because of its importance for people’s well-being and success, researchers and practitioners alike have wondered what, if anything, can be done to improve trait EI in adults. The question is not trivial as traits are harder to change than knowledge or abilities, especially in adulthood. However, the fact that personality traits can change in response to life experiences shows that traits are somewhat malleable (Roberts, Caspi & Moffitt, 2003; Roberts & Mroczek, 2008). The current note examines the possibility of improving trait EI in adults. It provides brief answers to the following four questions: (1) Is it still possible to improve trait EI in adulthood? (2) How? (3) What are the benefits ―in terms of well-being, health, social relationships and work success – of such EI improvement and do such benefits last? (4) Will trait EI training work for everyone?

To What Extent Can Trait EI Be Improved In Adulthood?

This question has given rise to a number of studies, mainly in the fields of psychology, management, medicine and education. As these words are being written, 46 studies have been conducted to check whether trait EI scores improve after EI training (for review, see Kotsou, Mikolajczak, Grégoire, Heeren & Leys, in preparation). 90% of them conclude in the affirmative. However, a closer look at the studies reveals that most of them were published in low-impact factor journals (median Impact Factor < 1), which is not surprising as the vast majority of them suffer from crucial limitations, the most important being that 46% of the studies do not include a control group. Among the studies that did, only 36% assigned participants to groups randomly and only 8% of the studies (i.e., 2 out of 46) included an active control group (i.e., a training group with the same format but another content; the only way of excluding the fact that improvements are due merely to the group effect). Moreover, 63% of the studies measured training effects immediately after the training, with no follow-up to assess the sustainability of the changes.

Finally, 75% of the studies did not use a theory- and/or evidence-based training. A theory-based training is a training that is designed according to a theoretical model of emotional intelligence (e.g., if the model comprises 5 dimensions, the training should cover all of them; if the model assumes a hierarchical order in the EI dimensions, the training should be built accordingly). An evidence-based training is a training in which the individual strategies taught to participants to improve EI (e.g., strategies to express their emotions in a constructive manner, strategies to regulate their emotions, etc) have been previously shown to be effective in well-designed scientific research.

That being said, a few studies did not suffer from the above-mentioned limitations (i.e. Karahan & Yalcin, 2009; Kotsou et al., 2011; Nelis et al. 2009, Nelis et al. 2011; Sharif & al., 2013; Slaski & Cartwright, 2003; Vesely, Saklofske & Nordstokke, 2014; Yalcin, Karahan, Ozcelik, & Igde, 2008). And they suggest that it is possible to improve trait EI in adults. The mean improvement of EI in these studies, as measured by the TEIQue or the EQ-I, was 12.4%. This increase was confirmed, although to a much lesser extent (+6.6%), by spouses and friends.

How can trait EI be improved in adults?

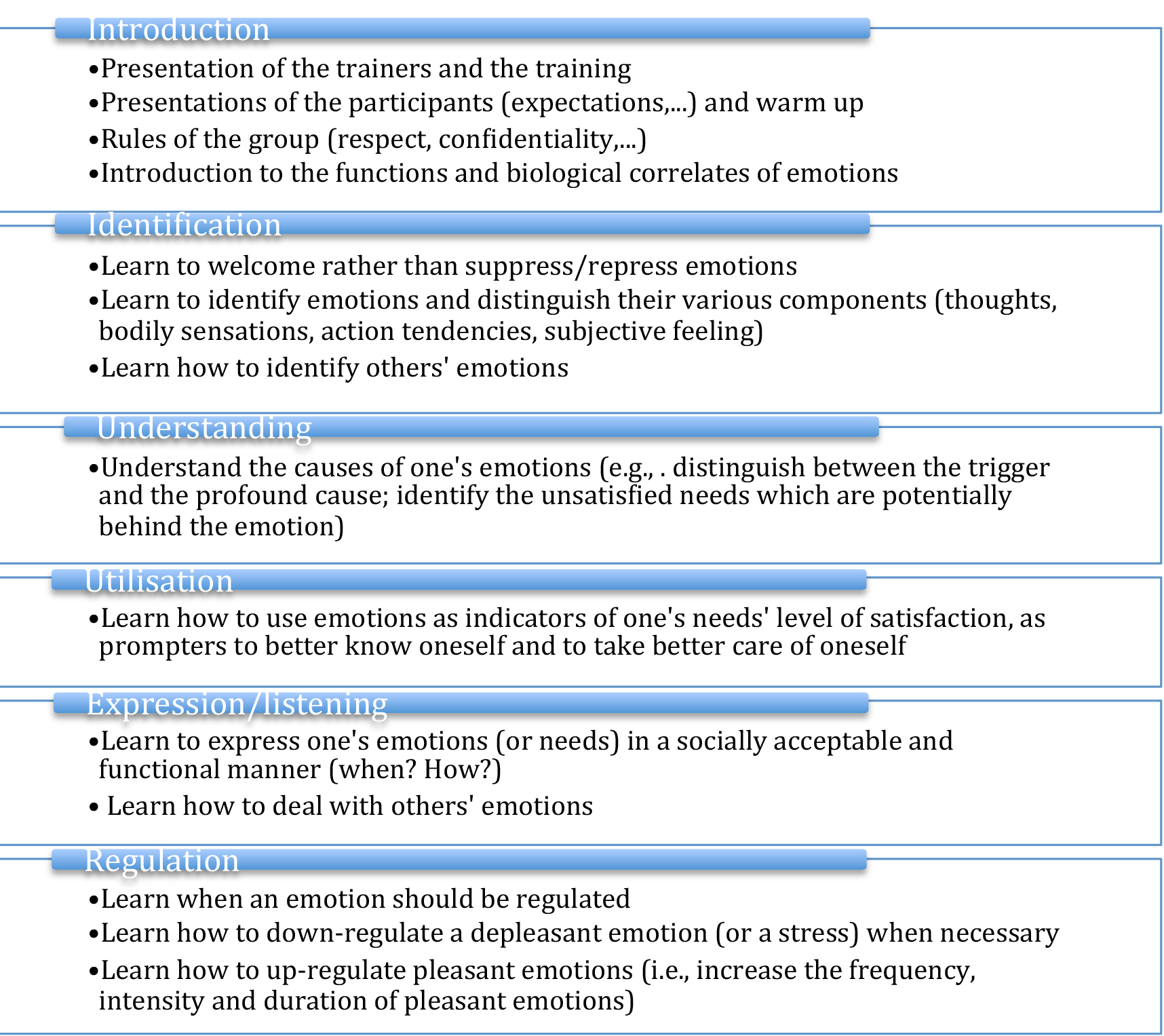

A look on the content of effective EI trainings suggests that improving trait EI requires working on at least two of the following EI dimensions: identification of emotions, expression of emotions and regulation of emotions. Among the well-designed studies cited above, the majority focused on five dimensions: identification, understanding, use, expression and regulation of emotions (see Table 1 for an explanation of these dimensions). We reproduce below the content of one of those trainings (Kotsou et al., 2011).

Like in most EI trainings, the pedagogical technique combined theoretical instructions with behavioral and experiential teaching methods (e.g., group discussions, role play, self-observation, etc. The full materials are available in French on request to the first author). We won’t be able to get into the details of how these forms of training work (please contact first author for further details), but to get a flavor of our techniques we will say a few words about the sort of role play we do in the “expression/listening” module.

In this role playing game the trainer invites one participant (A) to play the role of a person who has just been left by his partner. Another participant (B) is invited to take the role of the friend that A has called for support. A is usually very emotional when explaining the situation to B. The group observes how the B deals with the situation. After a few minutes, the trainer interrupts the session and asks A how s/he feels. Usually, s/he still feels very emotional. The trainer then invites another participant to play the friend. The scene is repeated until someone finds a way to make A feel better. The trainer then asks the group why the first interventions did not work, and why they think that the last did. This then allows the trainer to explain the most common ways people react when someone shares an emotional event with them (asking questions about the facts, offering solutions, minimizing, judging, reappraising…) and discuss why these ways of listening do not work well, even if most of them are well intentioned. He then explains why the last solution (reflecting feelings) works better, and when reappraising and offering solutions can have positive effects (i.e., only after the negative emotion has significantly decreased).

Which Benefits Can Be Expected From Trait EI Improvement?

The first benefit is enhanced psychological well-being: EI training leads to both a drop in psychological symptoms (stress, anxiety, burnout, distress, etc.; Karahan & Yalcin, 2011; Kotsou et al., 2011; Nelis et al., 2011; Sharif et al., 2013; Slaski & Cartwright 2003; Vesely et al., 2014), and an increase in happiness (well-being, life satisfaction, quality of life etc.; Kotsou et al., 2011; Nelis et al., 2011; Vesely et al., 2014; Yalcin et al., 2008). Unsurprisingly, these changes translate into significant changes on personality traits of neuroticism and extraversion after a few months (Nelis et al., 2011).

The second benefit of EI training is an improvement in self-reported physical health (Kotsou et al., 2011; Nelis et al., 2011; Yalcin et al., 2008). It is noteworthy that this improvement in physical health is also evidenced in biological changes such as a 14% drop in diurnal cortisol secretion in Kotsou et al. (2011)’s study and a 9.7% drop in glycated hemoglobin in Karahan & Yalcin’s (2009).

The third benefit is improved quality of social and marital relationships (Kotsou et al., 2011; Nelis et al., 2011) with, this time, a remarkable agreement between participants and friend/spouse reports. The fourth benefit concerns work adjustment. EI training increases people’s attractiveness for employers (see Nelis et al., 2011, study 2 for the detailed procedure) and work-related quality of life (Slaski & Cartwright, 2003). It is however unclear whether an improvement in EI increases work performance. Although several studies report an effect of EI training on work performance, the only well-conducted study that measured work performance did not observe any effect (Slaski & Cartwright, 2003).

One may wonder whether the foregoing changes generated by EI training last. From the well-conducted EI training studies that included a follow-up, it can be concluded that the changes in trait EI and its correlates are evident after a few weeks and are maintained for at least 1 year (see Kotsou et al., 2011). No study so far has tested whether these changes last more than 1 year. Studies with longer follow-up periods are however needed to ascertain that benefits in terms of well-being are resistant to hedonic treadmill effects, namely the tendency of most humans to return to their baseline level of happiness after major positive or negative events or life changes.

Does Trait EI Training Work For Everyone?

From the many studies conducted in our lab (most of them as yet unpublished master’s theses), we have observed that EI training seem to be effective for both women and men, both younger and older adults, both normally gifted as well as exceptionally gifted people, for both sub-clinical and non-clinical samples and for both psychosomatic as well as condition-free patients. In all these groups, people with the highest motivation to follow the training derived the largest the benefits of it. By contrast, standard EI training is not effective for severely depressed in-patients or for unqualified workers from very low socio-economic backgrounds. In these two groups, people did not really adhere to the training (depressed people did not believe that it would help them get better; unqualified workers did not understand the usefulness of understanding and/or regulating emotions). Futures studies will have to determine if new versions of EI training could work better.

In conclusion, the current state of the literature suggests that trait EI can be improved in adults and that EI training is effective to that end. Future research is needed to determine the best methods to maximize the size and the duration of the effects, and to determine for whom it works the best/the least.

References

Andrei, F., Siegling, A. B., Baldaro, B., & Petrides, K. V. The incremental validity of the Trait Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire (TEIQue): A systematic review of evidence and meta-analysis. Article under revision.

Bar-On, R. (2004). Emotional quotient inventory: A measure of emotional intelligence: Technical manual. Toronto, Canada: Multi-Health Systems Incorporated.

Brasseur, S., Grégoire, J., Bourdu, R. & Mikolajczak, M. (2013). The Profile of Emotional Competence (PEC): Development and validation of a measure that fits dimensions of Emotional Competence theory. PLoS ONE, 8(5): e62635.

Karahan, T. F., & Yalcin, B. M. (2009). The effects of an emotional intelligence skills training program on anxiety, burnout and glycemic control in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients. Turkiye Klinikleri Journal of Medical Sciences, 29, 16-24.

Kotsou, Mikolajczak, Grégoire, Heeren & Leys. Improving emotional competence: A systematic review of the existing work and future challenges. Article in preparation.

Kotsou, I., Nelis, D., Gregoire, J., & Mikolajczak, M. (2011). Emotional Plasticity: Conditions and Effects of Improving Emotional Competence in Adulthood. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96, 827-839.

Malouff, J. M., Schutte, N. S., & Thorsteinsson, E. B. (2014). Trait Emotional Intelligence and Romantic Relationship Satisfaction: A Meta-Analysis. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 42, 53-66.

Martins, A., Ramalho, N., & Morin, E. (2010). A comprehensive meta-analysis of the relationship between emotional intelligence and health. Personality and Individual Differences, 49, 554-564.

Mayer, J.D., & Salovey, P. (1997). What is emotional intelligence? In P. Salovey & D.J. Sluyter (Eds.), Emotional Development and Emotional Intelligence: Educational Implications. (pp. 3-31). New York: Basic Books.

Mayer, J. D., Salovey, P., Caruso, D. (2002). Mayer-Salovery-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test. Toronto, Canada: Multi-Health Systems Incorporated.

MacCann, C., & Roberts, R. D. (2008). New paradigms for assessing emotional intelligence: Theory and data. Emotion, 8, 540–551.

Mikolajczak, M., Petrides, K. V., Coumans, N., & Luminet, O. (2009). The moderating effect of trait emotional intelligence on mood deterioration following laboratory-induced stress. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 9, 455-477.

Mikolajczak, M., Avalosse, H., Vancorenland, S., Verniest, R. Callens, M. van Broeck, N. Fantini-Hauwel, C. & Mierop, A. (in press). A Nationally Representative Study of Emotional Competence and Health. Emotion.

Nelis, D., Kotsou, I., Quoidbach, J., Hansenne, M., Weytens, F., Dupuis, P., & Mikolajczak, M. (2011). Increasing Emotional Competence Improves Psychological and Physical Well-Being, Social Relationships, and Employability. Emotion, 11, 354-366.

Nelis, D., Quoidbach, J., Mikolajczak, M., & Hansenne, M. (2009). Increasing emotional intelligence: (How) is it possible? Personality and Individual Differences, 47, 36-41.

O’Boyle, E. H., Humphrey, R. H., Pollack, J. M., Hawver, T. H., & Story, P. A. (2011). The relation between emotional intelligence and job performance: A meta‐analysis. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 32, 788-818.

Petrides, K. V. (2009). Psychometric properties of the Trait Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire (TEIQue). In C. Stough, D. H. Saklofske, & J. D. A. Parker (Eds.), Advances in the measurement of emotional intelligence. New York: Springer.

Roberts, B. W., Caspi, A., & Moffitt, T. E. (2003). Work experiences and personality development in young adulthood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 582-593.

Roberts, B. W., & Mroczek, D. (2008). Personality trait change in adulthood. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 17, 31-35.

Sharif, F., Rezaie, S., Keshavarzi, S., Mansoori, P., & Ghadakpoor, S. (2013). Teaching emotional intelligence to intensive care unit nurses and their general health: a randomized clinical trial. International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 4, 141-148.

Schutte, N. S., Malouff, J. M., Bobik, C., Coston, T. D., Greeson, C., Jedlicka, C., Rhodes, E. & Wendorf, G. (2001). Emotional intelligence and interpersonal relations. Journal of Social Psychology, 141, 523-536.

Slaski, M., & Cartwright, S. (2003). Emotional intelligence training and its implications for stress, health and performance. Stress and Health, 19, 233-239.

Vesely, A. K., Saklofske, D. H., & Nordstokke, D. W. (2014). EI training and pre-service teacher wellbeing. Personality and Individual Differences, 65, 81-85.

Yalcin, B. M., Karahan, T. F., Ozcelik, M., & Igde, F. A. (2008). The effects of an emotional intelligence program on the quality of life and well-being of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Educator, 34, 1013-1024.