Carolyn Zahn-Waxler, Honorary Fellow, Center for Healthy Minds

An interview with Eric Walle (May, 2019)

Carolyn Zahn-Waxler is an Honorary Fellow both at the Center for Healthy Minds and the Center for Child and Family Wellbeing at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. She spent her career as a Research Psychologist at the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) in Bethesda, MD, in the Intramural Research Program. She was past editor of the journal, Developmental Psychology, past President of APA Division 7, and recipient of the G. Stanley Hall Lifetime Achievement Award. She has published more than 175 scholarly papers and chapters on the development and socialization of empathy and prosocial behavior, coping, psychopathology and gender.

I’d like to start with your personal history. Where did you grow up? What did your parents do? What was your family like?

I grew up in a small town on a peninsula in northeastern Wisconsin. Often called the Cape Cod of the Midwest, it is known for its rugged beauty: cliffs along coastlines, forests of birch and pine, and farmlands. It was an idyllic, carefree place to grow up, playing with friends and roaming the countryside. We hiked and biked, walked beaches, and swam in Lake Michigan or Green Bay. We had a lot of freedom to come and go as we pleased. My father was a banker and active in the community, while my mother was a housewife. She envisioned more for herself than wife and mother. But that was not to be, due both to the role of women in the mid-20thcentury and to her own emotional problems. Early on my younger sister and I were largely unaware of her struggles and those of my father. But there were dark times ahead. Their arguments often took center stage in family life. My sister and I were sidelined and swept into whirlwinds of their negative emotions.

My mother sometimes took her unhappiness out on me. She resented my intelligence and the fact that I would go to college, something she had not done. There were also times when we enjoyed each other’s company as we had many common interests. She was often very funny, though her moods could shift on a dime. In retrospect, it was here that I likely developed my strong drive to understand people’s responses to human suffering, i.e. with healthy empathy vs. too much empathy, or avoidance or antipathy/disdain. My mother told me that I was selfish and uncaring. I learned over time that I was caring, even though I could not help her.

About 10 years ago I wrote a memoir chapter where I talk about how these early experiences affected my later life, both personally and professionally. It was for a book edited by Steven Hinshaw, titled Breaking the Silence. It is about professionals’ disclosures of mental illness in their families, themselves, or both. My chapter is about intergenerational transmission of depression, from a psychological perspective. Often it strikes a common chord in people, even though specifics vary. Tolstoy’s book, Anna Karenina, opens with the quote that all happy families are alike, but each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way. It’s not that simple of course. But there’s a kernel of truth. It’s probably not coincidence that there are many more kinds of negative emotions than positive emotions. Anger, fear, guilt, sadness, shame, disgust and more. Suffering is pervasive. This may be one reason negativity bias exists, beginning in childhood. I do ascribe to a functional theory of emotions. All emotions exist for a reason. They are adaptive and have survival value. But they can easily become dysfunctional.

About 10 years ago I wrote a memoir chapter where I talk about how these early experiences affected my later life, both personally and professionally. It was for a book edited by Steven Hinshaw, titled Breaking the Silence. It is about professionals’ disclosures of mental illness in their families, themselves, or both. My chapter is about intergenerational transmission of depression, from a psychological perspective. Often it strikes a common chord in people, even though specifics vary. Tolstoy’s book, Anna Karenina, opens with the quote that all happy families are alike, but each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way. It’s not that simple of course. But there’s a kernel of truth. It’s probably not coincidence that there are many more kinds of negative emotions than positive emotions. Anger, fear, guilt, sadness, shame, disgust and more. Suffering is pervasive. This may be one reason negativity bias exists, beginning in childhood. I do ascribe to a functional theory of emotions. All emotions exist for a reason. They are adaptive and have survival value. But they can easily become dysfunctional.

I especially like sharing the memoir with students. Their stress levels, anxiety and depression are at all-time highs, across disciplines. They may worry that their problems and family histories might prevent them from being objective. Students may think they are different from their teachers and professors, who appear competent and functional. But when you’ve been in the field long enough, as I have, you know that’s just not the case. Much lies hidden below the surface in all of us. Many highly successful academics (and people in all kinds of careers) also deal with mental health issues. Stigma is still deep-seated. Few chapters were written by people who were already mid-career and tenured. Even they must have worried about their reputations. To students I would say, find someone safe to share your feelings and seek help for yourself. If you work in a climate where it is possible to be more open all the better.

But weren’t nervous? I’m really struck that you felt comfortable disclosing everything that you did in that chapter.

I had no reason to be nervous. Remember that I wrote it when I had been retired and away from NIMH for several years. It would not have been wise to do when I was still at NIMH. Especially there, it would have been seen a sign of weakness and vulnerability. There was an implicit message that you had to be strong and healthy to study mental illness. Best to be different from “them”, so that bias would not infiltrate your work. How ironic is that? I learned over time that life experience can richly inform research rather than bias it. After I retired, I realized at a deeper level the fully intertwined nature of my personal and professional lives. Self-disclosure benefits others so it’s something I like to do.

Do you mind sharing a little bit about what were like as a child? What personal and professional ambitions did you have as a child? Were you successful in your early schooling? Did you always have a curious streak?

Oh sure. I did well in school and that was a source of satisfaction. I think I got some of my curiosity from my mother through her (over) sharing of her mental illness and her intense interest in the personal lives of others. I feel like I was learning my profession early on. She would tell me about the problems of different family members, relatives, friends and community members. Sometimes in a judgmental way but not necessarily. She could observe what others didn’t see. She had an uncanny eye and penetrating insights.

She would take me to movies that most others would view as inappropriate for a child. I liked that she did this. It made me feel grown-up, as her companion. I can imagine other children being totally bored, but I was riveted. I remember watching the 1948 film about mental illness with her, The Snake Pit, starring Olivia De Havilland. It was about people living in an insane asylum (the term used back then). I was around 8 or 9. She also took me to All About Eve with Betty Davis and Ann Baxter; about a rivalry between an older and a younger movie star. This is one way I got hooked on understanding the (mainly unhappy) lives of others. I devoured books from the library on other’s personal lives and inner worlds. I still do, because there is so much that can be learned from literature and the arts.

Tell me about your time as an undergraduate and your path to pursuing higher education. What was that experience like? What was the focus of your early research?

I never would have obtained advanced degrees had it not been for men. The idea of college had been deeply ingrained by my father. He first told me I would go to college, when I was 6 or 7 years old; moreover, that it would be the University of Wisconsin. This really antagonized my mother. My father was the first in his family to go to college and it transformed his life. Initially I majored in languages, but once I took psychology, I found my calling. Herbert Pick was one of my professors and I especially enjoyed his classes. He did research on children’s learning and perception. I worked as a research assistant for him on projects with mentally retarded children living in an institution across the lake from campus. Herb was about to leave UW to take a position at Institute of Child Development at the University of Minnesota (ICD) and he encouraged me to apply. I had no plan for the future. I vacillated because I wanted to stay in Madison to be near a boyfriend. Herb persisted and one day he showed up with the application form. Without his encouragement, I would never have gone to graduate school.

My roommates in graduate school at ICD, also received clinical training in the Psychology Department. This assured that they would be gainfully employed with a Master’s Degree. But that was not for me. It would be too anxiety provoking, trying to help people deal with their negative feelings and relationship issues. That’s what I was running away from! As for research, I couldn’t even imagine how emotions could be measured – so soft, so wispy, so vague. It is ironic that I ended up making a career of studying perhaps the most elusive of all emotions. I wanted to use experimental designs that would provide rigor, control, and straightforward answers to research questions. Little did I know then. For my dissertation I studied the role of different kinds of delayed reinforcement on discrimination learning. It was a topic my advisor John Wright was interested in, it fit my criteria for rigorous research, and was probably also the story of my career. There are long delays when you conduct longitudinal studies and have to wait for the answers!

Almost all of the professors were males and they uniformly supported the female students. I planned to stop with a MA, but the head of the department, Harold Stevenson, offered me a NIMH fellowship if I would stay and complete the PhD. At the next choice point, another professor, Robert Orlando, steered me firmly in the direction of a postdoctoral position at the NIMH Intramural Research Program in Bethesda, MD. My choices after obtaining the PhD were to go to NIMH as a post-doc, or to teaching jobs in small state colleges in California. California sounded more intriguing, but Bob emphatically explained (it felt like a decree) that I would not be able to do research there. That it would be a poor career decision.

I am curious to hear about your time working at the National Institute of Mental Health. What was that experience like?

I was fortunate to receive a tenured position there, but it came with significant restrictions. I would not be allowed to have a budget or staff to conduct my own research. The two male leaders of the NIMH Intramural Program, a psychologist and a psychiatrist, were trying to help in ways that were possible at the time. They wanted to support the work of Marian Radke-Yarrow, the woman who had hired me. At the time the agreement felt gentle because I was busy learning about naturalistic methods and different ways to observe young children’s emotions and behaviors.

I’ve only ever been in at a university, but I always imagined that the Intramural Research Program at NIMH would be isolating with regards to the lack of colleagues and opportunity for discussion. Were there trade-offs that you found between being at a research versus a university setting?

Like you, I only worked in one setting, so I have no direct basis for comparison. It was isolating because we didn’t have many psychologists as colleagues there. At NIMH there were around 30 labs, all headed by men but for two. I was in one that was headed by Marian Radke-Yarrow, the Laboratory of Developmental Psychology. We had a few developmental psychologists and several male psychologists, reassigned from the Laboratory of Psychology. A new administration cleaned house to make way for biological work and neuroimaging studies. One of the reassigned men stated that it would be ‘over my dead body’ to work for a woman and he retired. The rest stayed in Marian’s lab and helped to create a hostile work environment. The only way she could obtain adequate resources to conduct her programmatic research was to squeeze them out. Over time, the developmental program grew, there were great post-docs, and visiting fellows from other countries. It was very stimulating.

When I was hired, post-docs were never, ever, put into permanent positions. The heads of the IRP gave Marian a slot for a full-time position for me. That would be equivalent to your tenure. But there was that important stipulation: I could never have resources to conduct my own research. It was called a ‘gentleman’s agreement’. I would always be tied to her. There was a written memo to that effect. There were few opportunities for women then. I was grateful at the time, but eventually it would create another ‘mother-daughter’ conflict about separation and independence.

During my tenure at NIMH, administrations changed several times, each intended to establish purer biological/genetic approaches. Relatively little research was done with humans. And when it was, the focus was on psychiatric disorders. Environmental factors were assumed to play little or no role. Once the two heads of the Intramural Program retired, the new leaders created a different agenda. They tried to eliminate work on behavioral, social, and psychological processes. They closed the Laboratory of Family Psychiatry and replaced it with the Laboratory of Biological Psychiatry. The Laboratory of Socio-Environmental Studies was closed. The Child Research Branch was closed after Richard Bell retired. The Laboratory of Psychology continued to exist, but with a different cast of characters. This coincided nicely with President Reagan’s funding ban on behavioral research in the extramural program that lasted for several years. It certainly had a chilling effect. In looking back now I am amazed at all that we accomplished. Marian’s lab continued for several years but eventually it too was closed. My section on Developmental Psychopathology was placed in the Child Psychiatry Branch, headed by the other female lab chief, Judith Rapoport.

Marian experienced the double whammy of being a woman and a behavioral psychologist. Actually, it was a triple whammy because within the National Institutes of Health, mental health was on the lowest rung of the ladder, compared with physical diseases (cancer, heart and lung, etc.). We found ways to work around the system when writing our research protocols, using language that had a more biological ring to it at the time. Affect was thought of as a biological process then, so we used affective terminology in our research protocols. We couldn’t refer to social or behavioral processes. It sounds completely silly now, but it got us through some hurdles then.

For years we remained hidden from view. We worked in a very large old English Tudor House previously owned by a wealthy family. It was situated on the top of a hill on campus, covered with trees – aptly named Tree Tops House. At one time it housed an experimental nursery school that the Kennedy children attended. Observation rooms were created for studying couples, families, and children. It had originally been for the Child Research Branch. It was perfect. But then they cut down many of the trees and our treasure became evident to others. After Marian retired, I was given the go ahead to refurbish the house. After I had done that, they took it away and gave it to a new lab. They gave me plenty of space in another location across the street from NIH. But I had to start all over again.

Wow, that’s fascinating. How did you manage the shifting landscape at NIH? Could you advocate for yourself?

I learned to work around the system, which I thought of as ‘acquired deviousness’. There was always a certain kind of wiggle room. I learned how to finesse situations. Periodically, we had external reviews by a group called the Board of Scientific Counsellors. My research reputation was growing. Reviewers questioned why I didn’t have my own budget and resources. This placed pressure on Marian to provide more resources and independence. But the administration did not provide additional resources for her to do so. She did share a couple research assistants and post-docs. I collaborated with Mark Cummings on studies of young children’s responses to anger and aggression between adults. The first one was on responses to their parents’ fights. Some toddlers tried to break up the fights and serve as peacemakers, certainly not a job for children! And I collaborated with Grazyna Kochanska on the early development of guilt, both adaptive and maladaptive forms.

So, Marian was someone you met as a post-doc and worked with for much of your professional career. Would you say that she was almost like a second advisor to you after you finished graduate school?

Well, that’s an interesting question. Yes, because I never had anybody advising me in those research areas during my graduate research. Later I realized it was because I’d never sought it out. I avoided research on social and dynamic processes, emotions in particular, because of my family background. Instead I took courses on perception, learning and cognition. There was a lot of focus then on ‘grand’ learning theories based on behaviors of rats and humans. Eventually I became disillusioned. So it was a fresh start when I went to work with Marian to learn new research methods, especially naturalistic observation. She pioneered this approach, one that we now take for granted. I learned so much from her personally and professionally. Our families were close as well. She taught me about homemaking, picking out furniture and carpets, even how to paint and wallpaper. Marian was wonderful during the period when I was a junior colleague.

The very first study I worked on was about learning concern for others (Yarrow, Scott, & Waxler, 1973). Preschool children were placed in different kinds of learning environments that could lead to prosocial behavior – concern for others. Marian used the term concern for others,and I think it’s still a good one because it’s broad enough to capture affective, cognitive and behavioral aspects of outer-and-other directed prosociality. There were 4 different training conditions. Children in a preschool came in small groups for several hours to a mini-preschool setting there, a few mornings each week for a six-week period. The group was with a ‘teacher’ who was either nurturant or non-nurturant (aloof/neutral), who would demonstrate different ways of caring for others. These conditions were crossed with two types of training methods. One involved use of didactic, symbolic situations only where children were taught caring behaviors using pictures or dioramas of animals and humans in distress. The other training condition also included learning how to help real people in distress. So, there were 4 different learning conditions in addition to a control group. Only one condition led to generalized altruism. This was when the child had both experienced warmth from the teacher and training that included both symbolic materials and real-life opportunities. We found the same patterns with these children six months later, and also in a replication with inner-city, low income children.

I spent the first couple years working on that project. Then we did other studies where Marian provided me with some opportunities for first-authored papers. Perhaps most notable were studies of the development of concern for others and child-rearing practices associated with different levels of empathic concern. My professional independence grew when I obtained outside funding for research on these topics. This happened roughly ten years into my career, through interactions with Robert Emde, a catalyst for my own research program. He and four other investigators in different locations had obtained a McArthur grant to start an interdisciplinary project on development in the first years of life. The entire group met once a once a year for almost a week in great locations, for cross-fertilization of ideas and collaboration on projects across sites. They provided small grants that allowed me to increase staff and to travel. Many friendships developed in this cooperative group setting. This where I met your mentor, Joe Campos, a wonderful man. Our paths crossed again when Bob Emde, Robert Plomin, Jerome Kagan and a group of behavior geneticists received another MacArthur grant to study early cognitive, social, and emotional development in a sample of MZ and DZ twins at the Institute for Behavior Genetics at the University of Colorado. Bob wanted us to join the research team for our expertise in measurement of different emotions, empathy in my case.

Wow, what an invigorating time that must have been.

It was indeed!

As a woman in the field of psychology, have you faced difficulties or discrimination that you had to overcome?

Yes indeed! I experienced discrimination throughout my career at NIH as did all of the women who worked there. I had worked there for 25 years when I was asked to mentor a male, child-psychiatrist, post-doc who began at a higher salary than my current salary. I declined and no one challenged my decision. Eventually, we had the fortune of having a woman in charge for a period of time, Susan Swedo. First, she was deputy director of NIMH and then the acting director. She strove to change the inequities by forming a committee of women to explore gender discrimination. We interviewed laboratory chiefs and did surveys. Outside reviewers compared research contributions of professional males and females. Some of the interviews of lab chiefs were fine, some were disrespectful, and some came on to the women. There was blatant disregard. Data collected from the reviewers with expertise in our areas of work were compelling. Women doing comparable work to men in terms of their scientific contributions were paid substantially less. This report got the attention of the administration. Finally, the administration acknowledged the problem with a ‘gender equity adjustment’, certainly a better alternative for them than a class action suit. Women who could show their accomplishments equaled those of men at a higher salary level were moved to that higher pay grade, so there were big salary bumps. There was also retroactive pay for the last few years.

It is interesting, in retrospect, that NIH ‘led’ the way for gender equity in salary. Discrimination is still rampant in so many other institutions. We were lucky to have a female leader for a while. Otherwise I don’t think it would have happened. I used my “gender equity adjustment” for a big down payment for a second house up in Door County. At the time we had no concrete plans for retirement. Morris had grown up in Washington, DC and was comfortable with spending the rest of our lives there. I was less enamored but didn’t have a clear vision of what to do next. That all changed after we bought the second home. Gender equity helped guide a decision eventually to move back to Wisconsin.

What a biased setting to work in. What advice would you offer to women?

Know that discrimination still exists and comes in many guises. Try to be aware of what needs to change, both in yourself and your environment. Women still undervalue their contributions more than men, not just in academia but throughout life. Women are also more likely to hesitate, to speak softly, and to assume an apologetic stance. Try to persist, to make yourself heard. And if you can’t speak easily, try to do it in writing. That’s another way to make your voice heard. I was quiet in my early years and needed to be nudged along. This happened through outside collaborations with people like JoAnn Robinson, Robert Emde and so many others who enriched my knowledge base and broadened my perspective. The corpus of work on concern for others could not have happened without them.

I’ve mentored many women – and some men as well – both formally and informally, at NIMH, the University of Wisconsin, and through collaborations with women at other sites. I still do. I love this process. I like to encourage and recognize of the value of younger people’s ideas. I have often been surprised by how little women especially think of their contributions and talents, and how important it is to explicitly acknowledge their worth.

You conducted some of the pioneering research on the development of empathy and prosocial behavior in infancy. How did you get interested in this topic of study?

Our interest was piqued by the first study with Marian on optimal learning conditions for concern for others. While we identified those conditions, we also realized the potential was already there even in the youngest children studied. It just required the right circumstances for its expression. So, we became curious about the origins of concern for others. We started another study, beginning with infants around the age of 1 and followed them over time to span 2.5 years using an expanded age-cohort design. This required the use of naturalistic observation. The situations required to observe empathy (and empathy related responding – a term used by Nancy Eisenberg), are not frequent or predictable in natural settings. So it is not feasible to send outside observers into home settings. Instead, we carefully trained mothers to make detailed observations of their children’s responses to others in distress, which they tape recorded just after a distress incident (e.g. pain, sadness, anger, fatigue). We also had mothers and examiners simulate distress in the home and report their responses. Next, we video recorded infants’ and toddlers’ reactions to simulated distresses in the lab, so we could code from the videos.

Experimental probes provided strong evidence for veridicality of mothers’ observations, in an era when mother reports were suspect. Here, observations were often richly, elaborately detailed. We obtained glimpses into aspects of family life (e.g. fights between parents, parental despair, harsh and guilt-inducing parenting practices) that we could not have seen otherwise. We could not use this approach for the larger scale longitudinal studies we wanted to do next. But once we demonstrated reliability and validity of mothers’ observations with the use of structured probes, we could use these probes in the rest of our work.

We did several longitudinal studies that began infancy, with children followed for anywhere between 2 and 20 years. We traced different developmental pathways linked both to dispositional and environmental factors. We began with normative samples and then expanded to risk populations. Pamela Cole and I did a study of preschool children at risk for developing conduct problems. We also worked with infants with a parent with bipolar disorder and then added mothers with unipolar depression. This happened because two child psychiatrists at NIMH approached us about adding our procedures for assessing social-emotional processes to their battery of measures of these children and their parents. One of them, Leon Cytryn, came to be known as the father of childhood depression – the first to identify depression as an illness that could afflict children as well as adults. We now take this for granted, but it was strongly challenged at the time.

I began to delve into literature based on psychodynamic and neo-psychoanalytic approaches to understanding family dynamics and parent-child interactions. This is how I came to the study of child and parent psychopathology, depression in particular, and parenting practices. I never sought it out. But when the opportunity emerged, I was more than ready. The final longitudinal study I did with Paul Hastings and Bonnie Klimes-Dougan was on the role of emotions in the development of psychopathology in adolescents. The very first longitudinal work coincided with the emerging domain of developmental psychopathology, initiated by people like Alan Sroufe and Dante Cicchetti. So we were on the forefront of that movement as well. Again, it was an exciting time in research. In studies of social and emotional development, in particular, it is important to be able to compare risk groups with groups of typical children and/or parents (i.e. screened for psychopathology). Most research on socio-emotional processes does not do this. It assumes normal or typical processes absent specific assessment. This is a problem.

Much like emotion, empathy is a term that is often lacking in definitional precision. How do you define empathy? Are there separate cognitive and affective components or are they integrated?

I do not like to use the word empathy alone for precisely that reason, when I talk about my research. I do use it in ordinary conversations and in settings like this interview. People outside of academia seem to have a common understanding of it as sympathy or concern for others. Concern for others was what we called it in the first study with Marian and I still use it today. It is outer-oriented and other-directed. For measurement purposes, I then divided it into three parts.

Concern for others, in my view, has three basic elements. One involves affect or emotion, which we measure via facial expressions, vocalics (e.g. cooing sounds) and sometimes postures (leaning in). One is about behavior – all the different prosocial acts on behalf of another – helping, comforting, sharing, protecting, defending, and more. And one is cognitive, reflected in awareness and exploration of another’s distress, measured through non-verbal gestures and verbal inquiries (Affect, Behavior, Cognition, or the ABC’s of empathy). We score the three components separately. We’ve also done global ratings that incorporate the three components. They are strongly interrelated, but there is also enough variability to warrant separate statistical analyses. The components behave differently in early development. Affective empathy occurs early and levels off with age, while behavioral and cognitive empathy increase over time. Emotions are not well characterized by stage theories. They may become more complex, nuanced, and regulated over time, but not as predictable stages.

So, to answer your question, the components are both separate and integrated. This reminds me of a review article I read many years ago, by Watson and Clark (1992) titled, “Affects Separable and Inseparable.” Measurement is always arbitrary and imperfect to some degree. There are infinite ways to carve nature at its joints. This is true of our conceptualization and measurement as well. But our operational definitions and measures have stood the test of time. At least they’ve provided a very good start.

I also became interested in measuring children’s maladaptive responses to others’ distress. They include (1) self-distress or personal distress – crying, whimpering; (2) overinvolvement in the other’s distress –trying to comfort distressed or angry parent – a kind of role-reversal; (3) lack of regard for the other – little or no awareness or interest in the victim; and (4) active disregard, being judgmental and hostile toward victim. Decety refers to the latter two categories, respectively, as passive empathy deficits vs. active empathy deficits. Each of the other four responses can be seen as an ‘opposite’ of empathic concern. These categories are not always mutually exclusive. Children can vacillate between concern for the other and personal distress; they can be both caring and hostile, and so forth. But many children develop different patterns that coalesce into styles; for example, a caring child, an indifferent child, a bullying child. They can become more trait-like.

Sometimes people use the word “empathic distress” to refer to a child’s inability to regulate emotions; when they see someone else in distress, they too feel distressed. In Hoffman’s theory, this contagion of emotional distress was the first stage on the way to mature empathy. But to call it empathic distress creates conceptual confusion. It is self-distress or personal distress. It is one opposite of empathic concern for the other, as it signals the need for caregiving. Two different systems are in place almost the onset of life. The infant/child who is distressed by the victims’ distress is in need of care. The one who shows concern for the other shows the potential to provide care. So, seeking vs providing caregiving, two completely different systems (Zahn-Waxler, Schoen, & Decety, 2018). They can operate in close conjunction, but are different both conceptually and functionally. I’ll talk more about that a bit later.

But again, one where you need the longitudinal data to actually refute something that other researchers might have questioned.

Almost everything of significance I’ve done requires the use of longitudinal designs. I’ll give you an example from our work on observed active disregard for others in the first years of life. In work with Soo Rhee at the University of Colorado-Boulder, we’ve found that early active disregard for the suffering of others predicts later antisocial behavior and psychopathic traits; at multiple time points across childhood, adolescence and adulthood, assessed by multiple observers. This points to the need for early interventions. The fact that active disregard occurs so early in development does not necessarily imply that it is innate. Others have shown a history of child abuse for young children who behave in this way.

So, with this term disregard, you seem to be describing instances where I see your distress but I’m not behaving in a prosocial manner. I’m curious how you’d view this in terms of someone who’s walking past a beggar on the street. Is that disregard? Or a doctor who’s causing pain to a patient. Would that be disregard?

I’d have a hard time answering those hypotheticals without more information. People step by others in need for different reasons. As for the doctor causing pain to a patient, it is a kind of disregard but not really what I mean. The doctor is so focused on his own needs that he does not think about those of the patient. I’m talking about something that is more judgmental (“you shouldn’t have done that”) or hostile (swatting at the victim), or sometimes laughter in young children This has more of an anti-social quality. It emerges later in development than concern for others and is seen in a much smaller proportion of the children. Joe Campos and I had a running disagreement after he saw videotapes of a couple of children laughing at the victim’s distress or saying, ‘you didn’t really hurt yourself’. Joe said, “That means the simulation doesn’t work. The children see through it. They know it’s fake and it’s not real.” But if it was fake, why are the children who act like this at 14 and 24 months, the same ones who later show antisocial patterns and psychopathic traits even into early adulthood. With Paul Hastings, we also replicated these findings with a sample of preschool children, followed into early grade school, with clinical levels of conduct problems. So the procedures were fine after all. The results were robust, replicable, and a good example of why longitudinal designs matter. You have to be very patient to do this kind of work. Answers emerge slowly.

How do you feel that the field of empathy has evolved since you began researching this topic?

Well, when we started to work in this area, we avoided use of the word empathy. It was seen as loose, slippery – feeling what the other is feeling (“I feel your pain”), well, how could that be? Feeling something inside of someone else’s body? Some saw it akin to paranormal processes and deemed it pseudoscience.

In the beginning, I would get unusual calls and letters from people. There was a priest who lived in Newcastle, PA who would call me late in the evening to talk about these ideas. It felt a little odd, but the conversations intrigued me. There was an Air Force Colonel who used to contact me. I can’t even remember why now. I had a cousin who believed our findings with young children were definitive proof of the existence of God. When Edwin Mitchell, the astronaut, had an out of body experience in outer space he founded the organization called IONS, the Institute of Noetic Sciences. One subdivision was called the Altruistic Spirit Program. I received a call from them one day, asking if I would like a small grant to study something related to empathy. I said yes, of course, and they provided partial funding for a study of concern for others in young children of depressed and well mothers.

The term empathy began to achieve greater credibility as a scientific construct when neuroscientists started to study it along with related constructs, such as affective resonance or emotional contagion. If you could show where it existed in the brain through neuroimaging studies, this is proof of its existence. Resonance, of course, is a whole-body experience. The philosopher Adam Smith defined sympathy as the ability to understand another’s perspective and to have a visceral/somatic or emotional reaction, which could lead to caring actions. We hear another’s cry; we see their facial, vocal and body expressions. This is part of how it ‘gets into’ our own bodies, or as some say, ‘under the skin’.

Adam Smith’s definition provided a framework for the later study of sympathy/empathy. It included cognitive, emotional, and physiological components that could be empirically assessed. Later the study of interconnections within the brain and between the brain and body would reveal more about dynamics that underly empathic processes. Jean Decety’s neuroscientific work and imaging studies of children across an age range helped to transform knowledge in this area. Around this time, some researchers began to study a related concept, namely compassion – defined as a deep awareness of the suffering of others and a desire to alleviate that suffering. Helen Weng and Richie Davidson at the Center for Healthy Minds at UW did neuroimaging studies to compare brain activity in adults before and after compassion training practices intended to heighten kindness both toward the self and the victim. I find this work to be powerful.

Concern for others is one of those ideas that draw people into the big questions about our roles in the universe – how we have evolved as humans, the nature of good and evil, our purpose on the planet, the nature of consciousness and self-other awareness, etc. Decety speaks of the moral brain. This includes integration of cognitive, emotional and motivational mechanisms, shaped through evolution, development, and culture, to facilitate how people should treat each other, with empathic concern as a guide to moral acts.

Do you think that research on empathy is moving in the right direction?

The short answer is yes and no, but mostly yes. Certainly, research has provided us with substantially more information about children’s moral lives. I consider kindness and caring for others as an essential component of morality. I see human concern for others as part of our evolutionary history as mammals whose role, according to Paul MacLean, is to nurture and nourish their young. McLean’s view brought me more in tune with ways in which we are similar to other species.

MacLean proposed that empathy emerged with the evolution of mammals (and some avians) and what he termed “a family way of life.” This brought with it processes of extended caregiving, sensitivity to suffering, and responsiveness to distress cries of the young. MacLean emphasized interconnections of the limbic system with the prefrontal cortex, linked to parental concern for the young. This, in turn, provided the basis for the emergence of a more generalized sense of responsibility for the welfare of others. This suggests a deeply embedded capacity for concern for others that is part of our evolutionary heritage and history. Now, brain imaging methods of neuroscience have mapped out brain regions, processes and pathways consistent with MacLean’s early ideas, but with important elaborations.

Note that this argument emphasizes the role of parenting, more aptly the role of mothers, as females have mainly played this role throughout history. Only female mammals suckle their young. However, most theories about the course of human evolution, how we’ve established societies, how we’ve become less violent and more caring as a species, have been written by men. Some of them are quite funny actually, in a dark sort of way. One is that men killed off the bullies in order to create more peaceful societies. Well, all you have to do is look around you, my friends! There are enough weapons on planet Earth to destroy it. And enough bullies to dominate others and create widespread oppression. While active disgard emerges later than concern for others, and is much less common, its consequences are deadly.

What research studies do you view as exemplary of the type of research that there should be more of in the study of empathy?

I’ve already mentioned the work of Jean Decety. I value the contributions of Michael Tomasello and the people he has mentored like Warneken, Vaish, Hepach, Carpenter, and others. Vaish’s concepts of sophisticated and flexible concern for others in early childhood have been very helpful in advancing ideas about our human potentials. The work of Kiley Hamlin and her mentors also was ground-breaking. They showed that infants in the first year of life show a sense right and wrong, preferring helpful to harmful behaviors. Other important studies have been done with older children and adolescents. The contributions of Nancy Eisenberg and those she has mentored have been substantial. I appreciate her leadership in the field. Dale Hay is another person, as well as Judy Dunn. And I value the work of Daniel Batson who speaks of a pluralism of prosocial motives and studied these processes in adults. Eisenberg adapted his research designs to study these processes in children. And there are so many others, too many to name here.

The idea of positive affect as an important component of empathy is also gaining traction. Sharee Light and I (Light & Zahn-Waxler, 2011) have written about empathic cheerfulness during another’s distress as another form of prosociality. It consists of positive affect, like smiles, as social communication intended to change another’s negative mood state; to coax them out of their distress. This phenomenon also has been observed in studies of peer interactions with 6-month-old’s by Hay and 9- to 10-month-old’s by Liddle. Liddle showed that these efforts have some functionality; they seem to reduce the other baby’s distress.

So, if a communicative smile is instrumental in changing another’s behavior, is the caring response an emotion? A behavior? Both? This is where carving nature at its joints becomes tricky. This reminds me of the work of Frans de Waal, whose work I very much admire. He’s a primatologist who studies empathy in bonobos and chimpanzees and other species. If empathic concern for the other is an emotion, how do you code that in chimps? De Waal uses the term ‘consolation behaviors’ seen when other chimps rush over to comfort another in distress – and he slips in the word sympathy now and then. I was able to observe these consolation behaviors directly when I visited him at Living Links, the Yerkes’s laboratory outside of Atlanta, GA. We were busy talking to each other in an observation tower. One of the younger chimps who really liked Frans was trying to get his attention, but failed to do so. She became very upset and several other chimps rushed over to comfort her. Both emotion and action appeared to play a role.

What are some mis-steps or ill-advised directions have you seen in the study of empathy?

I think one way we got stuck in the field was getting into either-or arguments about human nature – all those variants of questions of whether we are primarily self-serving or focused on others. Human behavior is too multi-faceted to pose these kinds of either-or questions. In hindsight some of it seemed foolish and unproductive. Again, there are many ways of carving nature at its joints. And the carving goes way beyond the joints. Each time we ‘dissect’, we have the potential to create both fact and myth. It’s easy to get caught up in, what I find to be, dissatisfying conceptual arguments.

Overly simplistic cognitive developmental theories of morality and concern for others hindered the establishment of more sensitive models, that would focus as well on the role emotions and motives. This has started to change. But there are still those who believe that a moral sensibility is tainted or sullied by emotion. When I started to work in this area, cognitive models were dominant. Advanced morality required advanced cognition. This began with Piaget’s stage theory in which the young child is seen as egocentric and incapable. Kohlberg’s theory of stages of moral reasoning prevailed for some time. Here, emotion, including sympathy, was lower on the totem pole. Other theories, for different reasons, viewed young children in a similar light (e.g. learning theory, psychoanalytic theory).

Martin Hoffman’s seminal theory in the mid-70’s changed all that. He argued that true concern for others begins in the second and third years of life and proposed a four-stage theory. This was unique in that it ascribed potentials for empathy in very young children. The first stages were based on a few anecdotal observations, but the theory was productive in galvanizing the field into a different mindset. A part of the theory though remained tied to the idea that a certain level of cognitive understanding, of self as separate from the other, was a prerequisite for ‘real’ empathy. This is how I used to think about it too, until data proved otherwise. (The idea may reflect a Western cultural bias about the importance of the individual.)

More cognitively-based tests were established to assess the child’s ability for self-recognition/self-other differentiation. Because children’s ability to pass these tests didn’t occur until around 18 months, children were assumed not to show empathic concern until then. Cognitive theories were not the only ones to state that concern for others was impossible in the first year of life. Emotional theories of development made a distinction between primary, basic emotions and secondary, complex, or self-conscious emotions, like guilt, shame, empathic concern, envy and pride. Self-conscious emotions were thought not to appear until the second year of life because younger infants lacked the level of interpersonal awareness needed. Mothers could have told a different story had they been asked.

We had always started our longitudinal studies with infants at the beginning of the second year of life. That’s when we assumed empathic concern started. But when I met Maayan Davidov, she said “What about the first year of life?” And that question launched our current work, conducted in Jerusalem. I’m happy that this is now such a vibrant research area now. It stands in contrast to the views of people who beat up on empathy, calling it a fragile, narrow and parochial emotion. Yes, it can be seen as primitive in one sense due to its early appearance. But it is the forerunner of those qualities that allow us to care for others, stand up to bullies and fight injustice. It can also be seen as a strong emotion.

In large part, theories in philosophy and psychology were developed by males who didn’t spend much time around young children and hence were not privy to their rich social and emotional lives (Rousseau abandoned his four children to live in an orphanage). It goes all the way back to Socrates and ideas from Stoicism: passion must be subject to reason, emotions lead one astray. Descartes’s proclamation – I think therefore I am – further entrenched this line of thinking, and now we’ve seen it extended to “I think, therefore I feel.” Even on the surface it doesn’t make sense.

Shelley Taylor’s model of tend-and befriend, rather than fight-flight in explaining social dynamics provides a valuable perspective. It recognizes the role of positive social relationships and dynamics more common to females than males, that are also part of the expression and transmission of caring for others across generations. The model also shines a light on how male dominated theories of social-moral development and caring behaviors have led to constrained, often inaccurate models of prosociality. Sarah Hrdy, an anthropologist, is an important voice here, especially in her book “Mothers and Others” where she talks about the role women play in the development of mutual understanding, empathy, cooperation and collaboration. If we had had more intellectual foremothers, the story might have been different or revealed sooner. As more women entered the field and began to observe infants and young children, we’ve gained better knowledge of their early social-emotional capabilities. But we still have far to go. I don’t mean this as an attack on men. Women also have biases and preconceptions. It’s human nature. But we need to recognize how these views affect our theories, how we design our studies, and the overly broad generalizations we often reach based on limited research designs.

There are a number of developmental researchers who take that hard stance that there’s a cognitive aspect to empathy and an affective part, and that the two are distinct and in some ways the cognitive aspect is more important.

Well, I’ve already talked about that a bit. It’s just wrong-headed to pit cognition and emotion and then assuming that cognition has primacy.

Just to push back on that. Why would you say that the 3-month old is expressing empathy?

Here’s why. We distinguish between cognitive empathy and affective empathy in our codes. Both can be seen as early as 3 months, at least in a few children. Maayan Davidov and I have just completed a longitudinal study in Jerusalem, where we follow 3-month-old infants at several time points through 18 months of age. Both early affective and cognitive empathy (but not self-distress) predict later prosocial behavior, affective empathy being the strongest predictor.

What you’re saying challenges some of the prevailing thought in the field of empathic development, namely that the notion that the infant has personal distress and then is gradually able to regulate their own distress and thus attend to the needs of others. And you’re saying that it’s not that one develops from the other, it’s that they’re distinct to begin with.

Yes, I think there are two distinct systems. It’s true that infants have to be able to regulate their own distress before they can be helpful to others. But that does not mean self-distress represents a developmental stage, i.e. that it necessarily has to precede empathic concern. There are other infants the same age who do not show self-distress. Those who show early empathy are more prosocial later (Davidov, Zahn-Waxler, Roth-Hanania, & Knafo, 2013). We are excited about the evidence for very early origins of concern for others, and how this will alter existing developmental theories.

It’s hard to fight the orthodox view that all aspects of human development occur in stages and that cognition plays such a dominant role. How do you start to get alternative views into textbooks? Now I’m more fascinated with the variations among people. Why does someone become a caring person while another is less so, or is indifferent and/or actively uncaring? And why is someone concerned for others in a mature way, where there are healthy boundaries, so they don’t get absorbed by another’s distress? And if one is drawn in, how does this affect self-development? We’ve seen this with children of parents whose own emotional needs make it difficult to function as parents, e.g. some children with some depressed mothers. The child becomes overinvolved in trying to comfort the parent, to try to make him/her feel better. We’ve written a review article about the risk for children and adolescents (more often girls) (Zahn-Waxler & Van Hulle, 2012). We’ve also written more generally about typical sex differences; and how, at the extreme, they can become seen in different forms of psychopathology seen in males and females (Zahn-Waxler, Shirtcliff, and Marceau, 2008). I never set out to study differences in boys and girls. But they just kept popping up, and I decided to dig a little deeper – that curiosity thing again!

What you’re describing really gets at the importance, but also the difficulty, of examining individual differences in development.

Earlier in my career, individual differences were a nuisance. What was left unexplained was an irritant. Now I think they are of utmost importance for understanding why people differ so in their levels of concern and disregard for others. From these differences you can begin to create groups of individuals who are like one another. Then you can compare these groups in a number of different ways using person-oriented approaches. Also, we can construct sophisticated, transactional models that examine both parent and child characteristics related to group differences and developmental outcomes.

When I started working in the field, socialization was viewed as a one-way street. Parents influenced children period. Richard Bell’s seminal work on child effects changed all that. It was a revolutionary idea at the time. In hindsight it seems perfectly obvious that parents respond to and treat different children in the family differently – and that we need to consider how these processes interact. My first study of child-rearing practices and prosocial behavior was unidirectional in design. Then JoAnn Robinson used a person-oriented approach to examine continuity and change in concern for others from 14 to 20 months of age in our twin sample. She created groups of children who initially varied in their levels of concern for others. Some infants started high and stayed high over time, while others decreased. For children who started low, some of them increased over time while others did not. Patterns of change were predicted by child temperament, child rearing practices and family climate. The field now studies transactional processes more routinely; gene-environment interactions and analytic models have become more sophisticated. The work of Bakermans-Kranenburg and van IJzendoorn is a good example.

I noticed that even though you’re officially retired, you are still publishing empirical research. Can you tell me about your recent work?

It’s been 50 years since I first went to NIMH. So yes, it still remains a passion. Longitudinal studies are gifts that keep on giving. Younger colleagues and students take over the reins at later time points, bringing their own talents, interests, and expertise. And this can happen in many different ways. Several years ago, I read about the work of a talented Israeli investigator, Ariel Knafo. I invited him to take the lead on a behavioral genetics’ analysis of our large longitudinal study of cognitive and affective empathy in twins. Later he introduced me to Maayan Davidov, which led to a wonderful collaboration on the origins of concern for others that I’ve described.

What are some articles or books that have particularly influenced your thinking?

What are some articles or books that have particularly influenced your thinking?

Murphy, Lois (1937). Social behavior and child personality (sympathy research). New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Beers, Clifford (1908). A Mind that Found Itself. New York, NY: Longmans, Green and Co.

This book influenced my decision to major in psychology as an undergrad. Beers was institutionalized with major mental illness as a young man, recovered, and went on to establish the Mental Hygiene Movement in the US. It gave me hope.

Darwin, C. (1872). The expression of the emotions in man and animals.

Incidentally, he reported observations of sympathy for a crying nursemaid in his five-or six-month-old son.

Smith, Adam (republished in 1976). The theory of moral sentiments.

Miller, A. (1981). The drama of the gifted child: The search for the true self (originally published as Prisoners of Childhood) Basic Books

This was a good introduction to more a psychodynamic approach to understanding development.

De Waal, F. (2009). The age of empathy: Nature’s lessons for a kinder society.

In this and several of his other books, De Waal does a masterful job of reaching a more general audience on our interconnections with other species.

MacLean, P.D., 1985. Brain evolution relating to family, play, and the separation call. Archives of General Psychiatry, 42(4), pp.405-17.

Is there a specific article or study, either by you or someone else, that you feel deserves more attention than it has received?

The early study by Radke-Yarrow, et al., on learning concern for others is still timely but no longer receives attention. It is exemplary in design and relevant to application/intervention. However, older studies fade as new people enter the field and look for fresh discoveries – as each generation strives anew, part of the past is lost. This is especially true of the work of Lois Murphy, the mother of research on empathy. You rarely see her cited. She observed social and emotional development of preschool children. She did her dissertation on their expressions of sympathy (Murphy, 1937).

I also would like to see the edited volume by Stephen Hinshaw receive more attention. It’s relevant for many young psychologists going into clinical or scientific work, or both, for the reasons discussed earlier.

What about research endeavors that you did but failed? I always like to hear about these because I can’t read about them because they’re usually unpublished. Can you recall a specific research question or study that flopped?

I believe our basic research questions were sound. It’s a comfort and relief to see that when I look back. At the time you just don’t know, and I often felt uncertain. We were basically on the right track in our longitudinal studies. There has been sufficient replication across studies and reasonably consistent information about development and individual differences in concern for others.

Your recent work has focused on connecting scientific findings with real-world applications. Was this something that were always been passionate about or a more recent interest?

This was not of interest to me early in my career. By temperament and training I was drawn to basic research. We were taught, and so I believed, in science for the sake of science. Someone else would come along and find a way to use research results that might be meaningful in the real world. There was a kind of loftiness about it all. This was during an era when comparative studies of learning were being conducted with rats, children and adults, done by people like Howard and Tracy Kendler. As graduate students we were enamored with this work. So children, like rats, were simply research subjects.

Social relevance and application became more important to me several years later. I became more attuned to the potential value of our work on child-rearing practices for parenting interventions. For example, we’d identified a subgroup of depressed mothers, who engaged in positive childrearing practices. While maternal depression predicted later behavior problems in children, this was not true for the subgroup of children who had experienced proactive parenting. I wondered if these positive childrearing processes might be taught to depressed mothers in hopes of better outcomes for their children. I also thought more about how we might better educate the public about young children’s potentials for caring for others. But I did not work in the applied area.

When we moved to Madison 17 years ago, I connected with like-minded people doing translational research. I also started to practice meditation and learned of the scientific work being done here by Richie Davidson at his Center for Healthy Minds (CHM). I became an Honorary Fellow at CHM. Several years ago, he invited me to present my work at a week-long meeting at the Mind and Life Institute in upstate New York. There was a mix of scientists doing basic and applied work, and it was an eye-opening experience. It was kind of funny because we were in a very peaceful setting, in a beautiful old, large building in the country; originally a church, now with Buddhist décor. West Point was across the river and we could hear artillery in the background while we practiced our meditation. War and peace, separated only by a river.

Later I learned that Lisa Flook, Laura Pinger and Richie had developed a loving-kindness meditation curriculum for preschool children. I was intrigued, but skeptical, as to how meditation practices could be adapted for use with such young children to increase their concern for others. But this simply reflected the narrowness of my vision. When I read the curriculum and saw it implemented, my skepticism turned to wonder at the generalized caring and kindness shown by children. It shifted my mindset and I said, “This. This is what I really want to see happen.” I also work with people in the Center for Child and Family Well Being, within the School of Human Ecology (SOHE). Julie Poehlman-Tynan used compassion training with at-risk preschool children and wanted to include our measures of empathy. So, I trained coders to use our observational systems. I also created a legacy of financial support for research on depressed mothers and their children. Larissa Duncan who is with CHM and SOHE conducts research on pregnant woman and their infants; it begins with meditation training during pregnancy. A goal is to help women manage their stress and depression and to have more positive interactions with their children.

Wow, how inspiring. But it sometimes seems like people can’t get involved with the translational research until they are more senior in the field. Is this something you always wanted to do but never had the opportunity?

Well, as I’ve said, I became more sensitive to the importance of translational research as I continued to work with more risk populations. But I was not in a position to pursue such interests while employed by NIMH, for all of the reasons I described earlier. It certainly was not of interest to the government then.

What’s it like being back at the University of Wisconsin? Does it feel like you’ve come full circle?

I don’t know if it is as much about coming full circle, as it is about developing a sense of completion and closure. This interview has allowed me to look back, to reflect on my life and career with greater clarity and insight. So I thank you for your questions! I still work on a number of projects with younger colleagues and that will continue for some time. Last year my husband and I moved to Capitol Lakes Retirement Center in downtown Madison. It is a great place, meeting all of our physical, social, intellectual and cultural needs. We’ve made a lot of friends here. I do miss being around younger people. The Center for Healthy Minds is one way I can keep that up. It is located just a few blocks from where we live.

In the past we always had people living in our homes. We liked big houses and always had more space than we needed. We filled them with old pieces of furniture that my husband Morris had refinished. His father was an antiques dealer and made fine furniture, so Morris had a good eye and skilled hands for the work. We went antiquing on our first date and it remained one of our shared hobbies. When we lived out east, we housed people from other countries who came to work at NIH. When we lived here in Madison, it was a series of interns, undergrad and grad students, usually in psychology. We enjoyed many of the relationships that developed and still see some of the people. I collaborated with a few of the students, so this was another opportunity for mentoring.

And what non-academic interests are you currently pursuing? Staying busy, I presume?

I decided to retire after 35+ years and we moved to Madison. And we had purchased that second home in Door County, my place of origin. We were within walking distance of Lake Michigan but situated in forest, meadows and farm country. We had 16 acres for trailblazing and sunlight areas for gardening, which was one of my passions. I laid a meditation labyrinth there and we created the vestiges of a Native American Indian Village, complete with totem poles. This was the house that gender equity bought! We went back and forth from Madison to Door County for 17 years and sold the house up north about 3 years ago. I’m by nature a homebody, a nester. This is where I feel fully at peace. When I was active professionally, I learned to enjoy the adventure of travel, meeting new people and experiencing other cultures. But I only felt fully at peace when I returned to home and family.

When we first moved to Madison, I joined different women’s groups, mostly through our church, the First Unitarian Society. It was such a joy, because it wasn’t part of my life during my professional career. One is a group of Women Writers, where I first dipped my toes into creative writing. It stirs my imagination and provides a means to see life through a different lens. We also have a publication at Capitol Lakes called the Center Post, where I can publish this kind of work. It consists of residents’ writings and is published monthly. I joined the editorial board shortly after we moved. When they were looking for a new editor I volunteered. I enjoy this role and the opportunity to get to know more people. I’m also on a committee for successful aging here. One aspect of it concerns depression in older people which is commonplace and mostly ignored. And I must say, I still have my own moments. The tendency doesn’t just magically disappear. It requires tending. But the feelings become less raw with age.

I’m in a few groups of women who like to work with fibers (knitting, weaving, spinning, quilting, etc.). It is a time-old tradition and draws us deep into history. I like to design scarves and shawls. One group is a shawl ministry, knitting comfort items for others in the church and in the community. Some items are now sent to the border for migrants and their families. There’s something peaceful about knitting in a communal setting. My mother taught me to knit and also shared her love of cats. They’ve always been an important part of my life. I’ve developed quite a collection of cat objects over the years and they were recently on display at Capitol Lakes.

I’m in a few groups of women who like to work with fibers (knitting, weaving, spinning, quilting, etc.). It is a time-old tradition and draws us deep into history. I like to design scarves and shawls. One group is a shawl ministry, knitting comfort items for others in the church and in the community. Some items are now sent to the border for migrants and their families. There’s something peaceful about knitting in a communal setting. My mother taught me to knit and also shared her love of cats. They’ve always been an important part of my life. I’ve developed quite a collection of cat objects over the years and they were recently on display at Capitol Lakes.

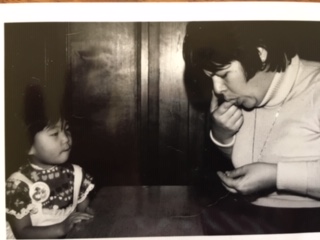

A current highlight is that we just celebrated our Golden Wedding Anniversary. We had a big party and had a chance to visit so many friends and family from different parts and pieces of our lives. My mother had never liked my boyfriends. But after she met my husband Morris she would say, “he’s a real peach.” And that he is. I feel fortunate to have married one of the most kind, compassionate human beings I know. He helped me stay steady through difficult times. I cannot imagine having the career I’ve had without his support. We have one child, Rebecca, who we adopted from Korea in the early 70’s. She was 4.5 months old at the time. We picked her up at Kennedy airport late in the evening and she came off the plane all smiles. She bounced around on our laps, blowing bubbles and making happy little sounds! She and her husband moved to Madison from out east several years ago. We felt blessed to have them here. Enthusiasm is still a big part of her personality.

This seems like a good place to stop!

The references listed below review information discussed above in more detail. Please contact me at czahnwaxler@wisc.eduif you would like any of this material.

Davidov, M., Zahn-Waxler, C., Roth-Hanania, R., & Knafo, A. (2013). Concern for others in the first year of life. Child Development Perspectives, 7(2), 126-131.

Light, S. & Zahn-Waxler, C. (2011). The nature and forms of empathy in the first years of life. In Empathy: From Bench to Bedside, J. Decety, Ed., MIT Press, 109-130.

Yarrow, M. R., Scott, P. M., & Waxler, C. Z. (1973). Learning concern for others. Developmental Psychology, 8,240-260.

Zahn-Waxler, C., Schoen, A., & Decety, J. (2018). An interdisciplinary perspective on the origins of concern for others: Contributions from psychology, neuroscience, philosophy, and sociobiology. In N. Roughley & T. Schramme, Forms of Fellow Feeling; Empathy, Sympathy, Concern and Moral Agency, Cambridge University Press.

Zahn-Waxler, C. & Van Hulle, C. (2011). Empathy, guilt and depression: When caring for others becomes costly to children. In Pathological Altruism. B. Oakley, A. Knafo, G. Mudhaven, & D. Sloan Wilson, Eds. Oxford University Press, New York, NY, 243-259.

Zahn-Waxler, C. (2008). The legacy of loss: Depression as a family affair. In S. Hinshaw (Ed.) Breaking the silence: Mental health professionals disclose their personal and family experiences of mental illness, Oxford University Press, 310-346.

Zahn-Waxler, C., Shirtcliff, E.A., & Marceau, K. (2008). Disorders of childhood and adolescence: Gender and psychopathology. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 4:11.1-11.29, 1-29.