Department of Human Development

I take the view that emotions are inherently social, and that the family is a crucial proximal context for emotional development. My research is informed by the dynamic systems (DS) perspective (Granic, 2005; Lewis, 2000). The DS perspective is metatheoretical in that it can be applied to any domain of inquiry. Indeed, it has roots in the disciplines of mathematics and physics as a set of formal equations to predict nonlinear changes (e.g., von Bertalanffy, 1969). In applying these ideas to emotional development, emotion researchers use generalizable DS principles that describe system dynamics and change over time to investigate emotions at multiple levels of analysis.

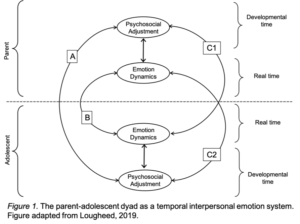

In my own work, I conceptualize the parent-child dyad as an emotion system, in which parents’ and children’s emotions are connected in time. Children internalize the ability to regulate emotions through the real-time dynamics of interactions with primary caregivers. How parents and children together manage the relative emotional upheaval during times of great developmental change (e.g., adolescence) can play a significant role in psychosocial adjustment later in development. My research on interpersonal emotion dynamics in parent-child dyads has recently led to a model of parent-adolescent dyads as temporal interpersonal emotion systems (Lougheed, 2019).

This article will describe my work using a DS perspective on emotion in the parent-adolescent relationship. First, I describe the DS approach I take to my research. Next, I discuss some of my research to date on emotion dynamics in parent-adolescent dyads. Finally, I describe my conceptual model of parent-adolescent dyads as temporal interpersonal emotion systems (TIES; Butler, 2011; Lougheed, 2019) and how it can inform future research.

A Dynamic Systems Approach to Interpersonal Emotion Dynamics

DS approaches are well-suited to the tasks of describing stability and change; nonlinear developmental processes; and complex system dynamics (Granic, 2005). The methods associated with the DS approach also offer a clear mapping between theory-based research questions and statistical analysis. The DS perspective emphasizes dynamic associations among multiple system components, with the higher-order structure of the system emerging from temporal associations among these lower-order components (Lewis, 2000). The principle of self-organization emphasizes the interconnection of multiple time scales, as higher-order structure of the system in turn constrains the dynamics of the lower-order system elements (Lewis, 2000). The result is a self-perpetuating system that evolves over time, perhaps becoming more entrenched in certain patterns and tendencies, or perhaps exhibiting structural reorganization with the introduction of novelty into the system dynamics (i.e., developmental change and major life events).

In my work, I have conceptualized parent-adolescent dyads as systems made of up two individuals whose emotion systems (i.e., within-person fluctuations in physiological arousal, experience, and behavioral expressions; Hollenstein & Lanteigne, 2014) dynamically interact with each other’s emotion systems. In line with others (Butler, 2011; Campos, Walle, Dahl, & Main, 2011), I conceptualize emotion regulation as a social process that unfolds in real time. Thus, I measure emotions in parent-adolescent interactions dynamically via multiple time-synchronized measures (e.g., physiological arousal, expressed emotions, self-reported emotional experiences). The overarching aim of my research program is to examine how emotion dynamics between parents and adolescents are associated with mental health symptoms in the family.

Emotion Dynamics in Parent-Adolescent Dyads

Emotion Dynamics in Parent-Adolescent Dyads

The focus of much of my research to date has been on interpersonal emotion dynamics between parents and children. In one branch of my research, I examined the interpersonal emotion dynamics of one of the most emotionally-intense parent-child relationships: mother-daughter dyads during adolescence. Adolescents gain autonomy within the family and age-typical changes to emotion dynamics (greater emotional intensity and negativity) play out in close relationships (Hollenstein & Lougheed, 2013; Rosenblum & Lewis, 2003). Adolescents—girls especially—also experience an increased likelihood of psychosocial adjustment difficulties (Galambos, Leadbeater, & Barker, 2004).

In two projects, my colleagues and I examined the links between mother-daughter emotion dynamics and psychosocial adjustment. First, we drew on social baseline theory (Beckes & Coan, 2011) to examine the interpersonal dynamics of sympathetic nervous system activity (an indicator of emotional arousal). According to social baseline theory, humans are a fundamentally social species and evolved to be in close proximity to other humans. Thus, the baseline of human functioning is social, rather than individual, and our physical closeness to relationship partners—in addition to our perceptions of relationship closeness—will lead to more efficient emotion regulation. We found that in the context of adolescent social stress, high relationship quality had the same buffering effect as physical contact (Lougheed, Koval, & Hollenstein, 2016). This study was the first to demonstrate that the tenets of social baseline theory play out in real-time dynamics. We also found that, in the context of positive mother-daughter interactions, daughters’ perceptions of relationship quality (and not mothers’ perceptions) was associated with the extent to which maternal emotional arousal was linked in time to daughters’ arousal (Lougheed & Hollenstein, 2018). In other words, mothers were more “in tune” with their daughters’ emotional responses if their daughters perceived a high degree of warmth and trust in the relationship.Second, we have also examined individual differences in mothers’ and daughters’ ability to adjust to changing emotional circumstances. One aspect of adaptive emotion regulation involves adjusting emotional responses to situational demands (Hollenstein, 2015). I developed a novel lab-based emotion elicitation task, the Emotional Rollercoaster task (Lougheed & Hollenstein, 2016), to examine how mothers and daughters adjusted to changing emotional circumstances. As expected, emotional rigidity (i.e., dyads did not adjust emotions according to changing contexts) was associated with lower relationship quality and higher maternal internalizing symptoms, whereas moderate levels of flexibility were associated with higher relationship quality and lower maternal internalizing symptoms.

In another branch of my research, I have focused on examining the temporal dynamics of parental responses to children’s and adolescents’ emotion expressions. Theoretical perspectives of emotion socialization emphasize that parental responses to their children’s emotions contribute to shaping youths’ tendencies to display and regulate emotions (Eisenberg, Cumberland, & Spinrad, 1998). Youth learn to regulate emotions through these repeated socialization experiences in the family, and this process predicts youths’ psychosocial adjustment (Morris, Silk, Steinberg, Myers, & Robinson, 2007). To date, one of the most common approaches to examine parental socialization of youths’ emotion has been to use parental-report questionnaires of their tendencies to respond to their children’s emotion expressions (e.g., Fabes, Leonard, Kupanoff, & Martin, 2001). Although this method has resulted in a much-needed body of work documenting parental tendencies to respond to a variety of specific emotions youth might express, it has a few limitations. One limitation is that it obscures the temporal process by which socialization occurs, which—I believe—is an important feature of the process.

I have explored the idea that the timing of parental responses to youths’ emotions is important by leveraging a statistical approach common in epidemiology: survival analysis. Survival analysis estimates the timing of event occurrences and can be used to examine how time-varying factors, such as children’s emotion expressions, influence the timing of parental supportive responses. Using this approach, I have examined how the timing of parental responses to youths’ negative emotion expressions varies by youths’ psychosocial adjustment. For example, in one study (Lougheed, Hollenstein, Lichtwarck-Aschoff, & Granic, 2015), I found that parents of children with externalizing symptoms did not differ from parents of typically-developing children in terms of the total amount (i.e., total duration and frequency) of supportive behaviors they expressed to their children during a conflictual discussion. However, the results of our survival analysis models—which examine behavioral timing—showed that parents of children with externalizing problems were much less likely than parents of typically-developing children to show supportive regulation in the moments that their children are expressing negative emotions. Thus, the effective use of parental supportiveness may depend less on its general use, and more on its contingent use in response to specific emotional expressions made by children. We have also used this approach to examine similar processes in parent-adolescent dyads (Lougheed, Craig, et al., 2016; Lougheed, Hollenstein, & Lewis, 2016), and more recently, I have expanded on this topic with a tutorial for developmental and emotion researchers to use this analytic technique with data that come from video-recorded behavioral observations (Lougheed, Benson, Ram, & Cole, 2019).

Parent-Adolescent Dyads as Temporal Interpersonal Emotion Systems

My projects to date have led me to consider the role that multiple time scales play in the interpersonal regulation of emotion in the parent-adolescent relationship. My previous research has explored the various ways that parents’ and adolescents’ emotions are connected in time. Building on these findings, I have put forward a conceptual framework of parent-adolescent dyads as temporal interpersonal emotion systems (TIES; Lougheed, 2019). This framework is inspired by Butler’s (2011) assertion that close relationship partners are TIES, and DS approaches which emphasize the interplay of multiple time scales in emotional development (Hollenstein, Lichtwarck-Aschoff, & Potworowski, 2013; Lewis, 2000). As such, I emphasize the need to consider the unique elements that individuals bring to the parent-adolescent dyadic system and highlight the complexity of dynamics within TIES.

My projects to date have led me to consider the role that multiple time scales play in the interpersonal regulation of emotion in the parent-adolescent relationship. My previous research has explored the various ways that parents’ and adolescents’ emotions are connected in time. Building on these findings, I have put forward a conceptual framework of parent-adolescent dyads as temporal interpersonal emotion systems (TIES; Lougheed, 2019). This framework is inspired by Butler’s (2011) assertion that close relationship partners are TIES, and DS approaches which emphasize the interplay of multiple time scales in emotional development (Hollenstein, Lichtwarck-Aschoff, & Potworowski, 2013; Lewis, 2000). As such, I emphasize the need to consider the unique elements that individuals bring to the parent-adolescent dyadic system and highlight the complexity of dynamics within TIES.

Multiple time scales (e.g., momentary dynamics in real time, longer-emerging patterns over developmental time) are focal in my conceptualization of parent-adolescent dyads as TIES. Figure 1 provides a conceptual representation of a parent-adolescent TIES. Dyads consist of two individuals whose own psychosocial adjustment set the foundation of the relationship (e.g., genetic heritability; see Path A in Figure 1). Each individual has their own self-regulating emotion system at the real-time scale, comprised of physiological arousal, emotional experiences, and expressions (represented as “emotion dynamics” in Figure 1). In TIES, each individual’s emotion system is interconnected to the other’s (Path B in Figure 1)—parents’ and adolescents’ emotions during interactions are dynamically interconnected (e.g., Amole, Cyranowski, Wright, & Swartz, 2017; Lougheed & Hollenstein, 2018). To Butler’s (2011) conceptualization of TIES I add the layer of multiple time scales. Specifically, real-time dynamics can coalesce into longer-term developmental patterns (e.g., psychosocial adjustment, such as internalizing symptoms and relationship quality) through repetition in during real-time interpersonal interactions (Granic, 2005). In other words, moment-to-moment interactions between parents and adolescents simultaneously forge deeper paths of psychosocial adjustment at the developmental time scale, while simultaneously both parents’ and adolescents’ psychosocial adjustment constrain how emotions are regulated moment-to-moment (Paths C1 and C2 in Figure 1).

To illustrate, consider a mother and her daughter. By the time the daughter has reached adolescence, these two individuals have a shared history of interactions that has forged recurring patterns of emotions during day-to-day interactions (B path in Figure 1). These interactions have been characterized by the mother’s dismissiveness of her daughter’s negative emotional experiences—the mother tends to respond to her daughter’s expressions of sadness by invalidating them. Consequently, the daughter has learned over time to avoid expressing sadness around her mother and to suppress those feelings when they arise, leading to difficulties regulating negative emotions. The daughter started to manifest some depressive symptoms around the onset of adolescence (bidirectional links between adolescent emotion dynamics and psychosocial adjustment in Figure 1). The daughter’s symptoms include increased irritability, which are related to greater conflict during her interactions with her mother. In this manner, the daughter’s depressive symptoms constrain the interpersonal emotion dynamics that arise during interactions with her mother—the interactions become more intensely negative, which escalates the mother’s dismissiveness of her daughter’s emotions. This becomes a cycle whereby the emotion dynamics within this relationship reinforce the daughter’s depressive symptoms, which in turn escalate the negativity of the mother-daughter interactions (C paths in Figure 1). The mother-daughter dyad in this way is a system whereby each individuals’ psychosocial adjustment and tendencies constrain the unfolding of emotion dynamics moment-to-moment, which in turn feedback into the higher-order structure of adjustment.

Future Directions

Conceptualizing parent-adolescent dyads as TIES provides a road map for research on parent-adolescent emotion dynamics. It is unlikely that any single study in the near future will comprehensively and simultaneously examine all three paths of the model presented in Figure 1. However, this theoretical framework can help researchers more carefully consider the role that timing might play in their study designs and how timescales map onto developmental processes in interpersonal contexts.

There could be numerous direct and indirect associations among the three paths that inform future research questions. For example, in TIES, do partners’ psychosocial adjustment contribute equally to emotion dynamics during interactions, or do either parents’ or adolescents’ adjustment tend to drive dynamics more than the other? To what extent are there interdyad differences in the interpersonal emotion dynamics observed in TIES, and to what extent are these interdyad differences associated with psychosocial adjustment? Are any of the paths more susceptible to reorganization in response to major life events or developmental transitions than others? The research design best-suited for examining parent-adolescent TIES are multiple burst designs (Nesselroade, 1991; Ram & Diehl, 2015), in which intensive observations of short time scale dynamics (e.g., video recorded observations of behaviors that are then microanalytically coded) are repeated longitudinally over longer time scales such as months or years. Such designs enable the analysis of how processes at long time scales emerge from processes at short time scales, and in turn, how momentary dynamics are constrained by longer-term development.

An example of such a design in the field of emotional development is a study by Lichtwarck and colleagues of parent-child dynamics in dyads who were receiving treatment for children’s externalizing problems (Lichtwarck-Aschoff, Hasselman, Cox, Pepler, & Granic, 2012). Moment-to-moment parent-child dynamics during conflict discussions were examined six times during a 12-week family intervention. The results of DS-based analyses indicated that families whose children showed improvements in externalizing symptoms had parent-child dynamics characterized by a period of destabilization and greater variability over the course of treatment. This destabilization is interpreted as the dyadic system becoming more flexible and open to external inputs (such as the objectives of the intervention) rather than remaining stuck in rigid, problematic interaction dynamics. Intervention studies such as these can show how changes in psychosocial adjustment track with changes in the moment-to-moment dynamics of the dyadic system; that as longer-standing structures such as externalizing symptoms change, so too do moment-to-moment interaction dynamics, and changes in patterns of moment-to-moment dynamics may facilitate growth and development in longer-standing structures.

Taken together, emotional development is nested within family relationships and multiple time scales. Conceptualizing parent-adolescent dyads as TIES will help us to better understand the complex processes by which emotion dynamics are implicated in the evolving parent-adolescent relationship.

References

Amole, M. C., Cyranowski, J. M., Wright, A. G. C., & Swartz, H. A. (2017). Depression impacts the physiological responsiveness of mother–daughter dyads during social interaction. Depression and Anxiety, 34(2), 118–126. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22595

Beckes, L., & Coan, J. A. (2011). Social baseline theory: The role of social proximity in emotion and economy of action. Social and Personality Psychology Compass,5(12), 976–988. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2011.00400.x

Butler, E. A. (2011). Temporal interpersonal emotion systems: The “TIES” that form relationships. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 15(4), 367–393. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868311411164

Campos, J., Walle, E., Dahl, A., & Main, A. (2011). Reconceptualizing emotion regulation. Emotion Review, 3(1), 26–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073910380975

Eisenberg, N., Cumberland, A., & Spinrad, T. L. (1998). Parental socialization of emotion.Psychological Inquiry, 9(4), 241–273. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327965pli0904_1

Fabes, R. A., Leonard, S. A., Kupanoff, K., & Martin, C. L. (2001). Parental coping with children’s negative emotions: Relations with children’s emotional and social responding. Child Development, 72(3), 907–920.

Galambos, N. L., Leadbeater, B. J., & Barker, E. T. (2004). Gender differences in and risk factors for depression in adolescence: A 4-year longitudinal study. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 28(1), 16–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/01650250344000235

Granic, I. (2005). Timing is everything: Developmental psychopathology from a dynamic systems perspective. Developmental Review, 25(3), 386–407. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2005.10.005

Hollenstein, T. (2015). This time, it’s real: Affective flexibility, time scales, feedback loops, and the regulation of emotion. Emotion Review, 7(4), 308–315. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073915590621

Hollenstein, T., & Lanteigne, D. (2014). Models and methods of emotional concordance. Biological Psychology, 98, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2013.12.012

Hollenstein, T., Lichtwarck-Aschoff, A., & Potworowski, G. (2013). A model of socioemotional flexibility at three time scales. Emotion Review, 5(4), 397–405. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073913484181

Hollenstein, T., & Lougheed, J. P. (2013). Beyond storm and stress: Typicality, transactions, timing, and temperament to account for adolescent change. American Psychologist, 68(6), 444. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033586

Lewis, M. D. (2000). Emotional self-organization at three time scales. In M. D. Lewis & I. Granic (Eds.), Emotion, development, and self-organization: Dynamic systems approaches to emotional development(pp. 37–69). Cambridge University Press.

Lichtwarck-Aschoff, A., Hasselman, F., Cox, R., Pepler, D., & Granic, I. (2012). A characteristic destabilization profile in parent-child interactions associated with treatment efficacy for aggressive children. Nonlinear Dynamics, Psychology, and Life Sciences, 16(3), 353–379.

Lougheed, J. P. (2019). Conflict dynamics and the transformation of the parent-adolescent relationship. In S. Kunnen, M. van der Gaag, N. de Ruiter-Wilcox, & B. Jeronimus (Eds.), Psychosocial Development in Adolescence: Insights from the Dynamic Systems Approach. New York: Routledge.

Lougheed, J. P., Benson, L., Ram, N., & Cole, P. M. (2019). Multilevel survival analysis: Studying the timing of children’s recurring behaviors. Developmental Psychology, 55(1), 53–65. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000619

Lougheed, J. P., Craig, W. M., Pepler, D., Connolly, J., O’Hara, A., Granic, I., & Hollenstein, T. (2016). Maternal and peer regulation of adolescent emotion: Associations with depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology,44(5), 963–974. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-015-0084-x

Lougheed, J. P., & Hollenstein, T. (2016). Socioemotional flexibility in mother-daughter dyads: Riding the emotional rollercoaster across positive and negative contexts. Emotion, 16(5), 620–633. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000155

Lougheed, J. P., & Hollenstein, T. (2018). Arousal transmission and attenuation in mother–daughter dyads during adolescence. Social Development, 27(1), 19–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/sode.12250

Lougheed, J. P., Hollenstein, T., & Lewis, M. D. (2016). Maternal regulation of daughters’ emotion during conflicts from early to mid-adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 26(3), 610–616. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12211

Lougheed, J. P., Hollenstein, T., Lichtwarck-Aschoff, A., & Granic, I. (2015). Maternal regulation of child affect in externalizing and typically-developing children. Journal of Family Psychology, 29(1), 10–19. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038429

Lougheed, J. P., Koval, P., & Hollenstein, T. (2016). Sharing the burden: The interpersonal regulation of emotional arousal in mother−daughter dyads. Emotion,16(1), 83–93. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000105

Morris, A. S., Silk, J. S., Steinberg, L., Myers, S. S., & Robinson, L. R. (2007). The role of the family context in the development of emotion regulation. Social Development, 16(2), 361–388. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00389.x

Nesselroade, J. R. (1991). The warp and the woof of the developmental fabric. In R. M. Downs, L. S. Liben, & D. S. Palermo (Eds.), Visions of aesthetics, the environment, and development: The legacy of Joachim F. Wohlwill(pp. 213–240). Hillsdale, N.J: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Ram, N., & Diehl, M. (2015). Multiple time-scale design and analysis: Pushing towards real-time modeling of complex developmental processes. In M. Diehl, K. Hooker, & M. J. Sliwinski (Eds.), Handbook of intraindividual variability across the lifespan(pp. 308–323). New York: Routledge.

Rosenblum, G. D., & Lewis, M. (2003). Emotional development in adolescence. In G. R. Adams & M. D. Berzonsky (Eds.), Blackwell Handbook of Adolescence(pp. 269–289). Malden: Blackwell Publishing.

von Bertalanffy, L. (1969). General system theory; foundations, development, applications. New York: G. Brazill