Political Science Department, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Introduction

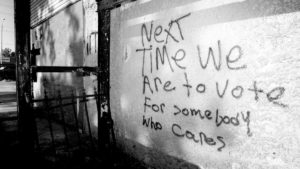

I have been asked to write about anger and politics. It would seem a good time to do so. In the United States today, in the time of President Trump, the word “anger” is tossed around a lot. People are angry, Trump is an angry man, we are living in angry times. A New York Timesheadline reads: “In a Divided Era, One Thing Seems to Unite: Political Anger.” (Peters, 2018) On the one hand, for political scientists who study emotions, these references to anger might be seen as grist for the mill. On the other hand, the various, diffuse, and ambiguous uses of “anger” make the word nearly meaningless. This problem is to be expected. Almost all emotion researchers agree that anger is one of a handful of basic emotions found across cultures. In many negative and intense situations, it’s natural that the word anger is commonplace.

The question here is how the word “anger” should be used for students of politics. Can “anger” be defined and conceptualized in such a way to make it useful for understanding variation in political actions and outcomes? How should we separate anger from other intense and negative emotions?

This brief piece on a big subject will proceed along the following lines. I will first outline a framework to break down and define emotions in a way accessible to most political scientists. I will then provide some examples of how political actors use emotions as a resource. With reference to the framework and examples, I will address why anger is central to political conflict and then identify important research avenues. I will conclude with a comment about anger in current US politics.

Defining Emotions for Political Scientists

Until very recently, political scientists have neglected the role of emotions. Most would be unfamiliar with the psychological terminology associated with emotions. Political scientists generally discuss individual political actions in terms of the interaction of preferences, information collection, and belief formation. In terms of decision theory, most political scientists are more familiar with rational choice theory than psychological approaches. Given the nature of this audience, I have borrowed a framework from the political philosopher Jon Elster and used that framework to illustrate the key elements of emotion in juxtaposition with a rational choice cycle.[1]

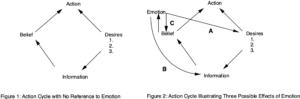

Figure 1 illustrates a rational action model. Starting on the right side of Figure 1, individuals are seen as holding a short list of stable and ordered preferences or desires. Given these preferences, individuals then collect information about how best to attain their goals. They form beliefs about the most effective means and strategies to gain what they want. An action then results as a combination of desires and beliefs.

Figure 2 incorporates Figure 1 but in this cycle belief also leads to emotion. Following many socially oriented theorists, emotion can be conceptualized as “thought that becomes embodied because of the intensity with which it is laced with personal self-relevancy.” (Franks and Gecas 1992: 8). As Ortony et al. write: “Our claims about the structure of individual emotions are always along the lines that if an individual conceptualizes a situation in a certain kind of way, then the potential for a particular type of emotion exists.” (Ortony et al.: 2) As emotion researchers will note, this treatment follows the line of appraisal theory of emotion.[2] Stated another way, beliefs are the cognitive antecedents of emotion. For example, when an individual comes to believe that the present situation is dangerous, the emotion of fear will arise. With anger, an individual believes that an individual or group has committed a blameworthy action against one’s self or group.

Anger will be most certain and most intense when the cognitive antecedents that generate the emotion are very clear. In the case of anger, the event creates a belief of a specific, easily recognized perpetrator committing intentional negative actions against a distinct target. There should be no ambiguity about the identity or purpose of the perpetrator. There must be an identified causal agent who can become a clear target for the urge to punish.

In Figure 2, three general effects of emotion may follow, marked as A, B, and C effects. First, and most fundamentally, emotions are mechanisms that heighten the saliency of a particular concern (A effect). This effect is closely related to emotion theorists’ idea of action tendency. The emotion acts as a “switch” among a set of basic desires. Individuals may value safety, money, vengeance and other goals, but emotion compels the individual to act on one of these desires above all others. Second, once in place emotions can produce a feedback effect on information collection (B effect). Emotions lead to seeking of emotion-congruent information. Third, emotions can directly influence belief formation (C effect) (Frijda et al. 2000). Emotions can be seen as “internal evidence” and beliefs will be changed to conform to this evidence. Even with accurate and undistorted information, emotion can affect belief formation. The same individual with the same information may develop one belief under the sway of one emotion and a different belief under the influence of a different emotion.

While emotions are a complex phenomenon that go beyond this simple framework, I developed it in hope of its ability to readily plug into some of the major questions in political science including preference formation, framing and processing of information, and the durability of attitudes and beliefs.

While this framework can address emotions in general terms, it also can be used to identify and specify the components of the specific emotion of anger. As mentioned above, anger forms from the belief that an individual or group has committed an offensive action against one’s self or group. Its A effects heighten desire for punishment and vengeance against a specific actor. Under the influence of anger, individuals become “intuitive prosecutors” specifying perpetrators and seeking vengeance (Goldberg et al. 1999). Anger’s B effects distort information in predictable ways. The angry person lowers the threshold for attributing harmful intent; the angry individual blames humans, not the situation (Keltner et al. 1993). Anger tends to produce stereotyping (Bodenhausen et al. 1994). Anger’s C effects shape the way individuals form beliefs. Under the influence of anger, individuals lower risk estimates and are more willing to engage in risky behavior.[3] In sum, regarding the key sub-phenomena of anger in relation to political violence, anger heightens desire for punishment against a specific actor, creates a downgrading of risk, increases prejudice and blame, as well as selective memory.[4]

Politics and Anger

At a fundamental level, politics is about means and ends. Political actors consider what means they have to gain and maintain power. Following this line, how would an emotion like anger fit into this means-ends view of politics? Here are three examples involving strategies of provocation.

1. Anger as a means to provoke an opponent into retaliation. How can a provocateur create anger in an opponent? The political actor tries to shape the beliefs of the opponent to fit an anger-inducing narrative. To be most effective, the opponent should perceive a clear perpetrator, perceive themselves as clear victims, and see the act as unjustifiable. If the intensity of anger is high enough, the opponent will be unable to restrain group members from anger’s action tendency (A effect) to seek vengeance. In this case, inducing anger in a target is a form of coercion. Under the sway of anger, an opponent can be compelled toward self-destructive forms of retaliation.[5] As mentioned above, under the sway of anger, individuals lower risk estimates (C effect). Because an angry opponent will downgrade the costs and risks of retaliation, they can be easily baited into over-reaction.

Anger-based provocations are a common strategy. Political actors seem to have intuitions about how to employ such strategies even if they have not thought through them in a systematic way. A slogan written on a giant draping mural in Tehran provides a vivid example. The caption reads, “America be angry and let that anger destroy you.” (Christia 2007) If the strategy aims for an immediate response, the provocation will have to match the anger narrative more closely. Along these lines, many commentators see Ariel Sharon’s visit to The Temple Mount in 2000, despite his claims to the contrary, as a famous example of an effective provocation. As reported in The Guardian:

Surrounded by hundreds of Israeli riot police, Mr. Sharon and a handful of Likud politicians marched up to the Haram al-Sharif, the site of the gold Dome of the Rock that is the third holiest shrine in Islam. He came down 45 minutes later, leaving a trail of fury. Young Palestinians heaved chairs, stones, rubbish bins, and whatever missiles came to hand at the Israeli forces. Riot police retaliated with tear gas and rubber bullets, shooting one protester in the face. The symbolism of the visit to the Haram by Mr. Sharon – reviled for his role in the 1982 massacre of Palestinians in a refugee camp in Lebanon – and its timing was unmistakable. “This is a dangerous process conducted by Sharon against Islamic sacred places,” Yasser Arafat told Palestinian television. Mr. Sharon’s second motive was less obvious: to steal the limelight from the former prime minister, Binyamin Netanyahu, who returned from the US yesterday and could become a challenger for the Likud party leadership after Israel’s attorney general decided not to prosecute him for corruption. But that ambition was overshadowed by the potential for serious violence at Haram al-Sharif, the point where history, religion and national aspiration converge. Palestinian protesters followed Mr. Sharon down the mountain, chanting “murderer” and “we will redeem the Haram with blood and fire.” (The Guardian, 2000)

Surrounded by hundreds of Israeli riot police, Mr. Sharon and a handful of Likud politicians marched up to the Haram al-Sharif, the site of the gold Dome of the Rock that is the third holiest shrine in Islam. He came down 45 minutes later, leaving a trail of fury. Young Palestinians heaved chairs, stones, rubbish bins, and whatever missiles came to hand at the Israeli forces. Riot police retaliated with tear gas and rubber bullets, shooting one protester in the face. The symbolism of the visit to the Haram by Mr. Sharon – reviled for his role in the 1982 massacre of Palestinians in a refugee camp in Lebanon – and its timing was unmistakable. “This is a dangerous process conducted by Sharon against Islamic sacred places,” Yasser Arafat told Palestinian television. Mr. Sharon’s second motive was less obvious: to steal the limelight from the former prime minister, Binyamin Netanyahu, who returned from the US yesterday and could become a challenger for the Likud party leadership after Israel’s attorney general decided not to prosecute him for corruption. But that ambition was overshadowed by the potential for serious violence at Haram al-Sharif, the point where history, religion and national aspiration converge. Palestinian protesters followed Mr. Sharon down the mountain, chanting “murderer” and “we will redeem the Haram with blood and fire.” (The Guardian, 2000)

Ariel Sharon’s provocation was successful because of the predictability of Palestinian perceptions. For many Palestinians the arch enemy of the Palestinian people was going purposely to a sacred Islamic site with a clear intention to insult. In the general terms of the anger narrative, an identifiable agent was intentionally committing a negative act against a specific target. As Sharon undoubtedly knew, anger would result. Under the influence of this emotion, violence could be expected.

2. Anger as a means of creating a spiral of violence. Anger is also a tool for creating spiraling cycles of violence that can transform an entire conflict. In this case, the actor tries to imbue the opponent with a revenge-inducing anger. When that opponent strikes out, perhaps with indiscriminate violence, one’s own side responds with anger and retaliation. The cycle turns. Zarqawi’s bombing of the golden dome in Samarra in February 2006 provides a prime example. Wishing to ignite a sectarian war, Zarqawi chose a symbol central to Shia identity. No one died in the bombing, but killing in this case was not central to the creation of anger. The action produced anger by the clarity of the cognitive antecedents underlying anger: A Sunni perpetrator group destroyed a sacred Shia site in an act of total disrespect and desecration. The quotations given to reporters after the bombing are textbook responses to an anger–based strategy:

“The war could really be on now,” says Abu Hassan, a Shiite street peddler who declined to give his full name. “This is something greater and more symbolic than attacks on people. This is a strike at who we are.” (Murphy 2006)

“If I could find the people who did this, I would cut him to pieces,” said Abdel Jaleel al-Sudani, a 50-year-old employee of the Health Ministry, who said he had marched in a demonstration earlier. “I would rather hear of the death of a friend, than to hear this news.” (Wong 2006)

Within hours of the attack, thousands of Shiites took to the streets in protest, many of them brandishing arms. Over twenty Sunni mosques were burned in retaliation.[6]

3. Anger as a means of drawing in a third party. This tactic has been employed in a wide variety of situations. Some leaders of the US civil rights movement believed that provoking violence from opponents might create anger in third parties who would then be motivated to act. As Doug MacAdam and Ron Aminzade have written:

(t)here is the baiting of authorities into acts of official violence which tends, unless the repression is extreme, to reinforce group solidarity and the shared resolve to “fight again another day.” These exercises in strategic provocation may have an additional emotional payoff for the movement. Violence by authorities that is widely perceived to be illegitimate may, as in the case of the U.S. Civil Rights Movement, anger an otherwise disinterested news media and general public, who, in turn, respond with the kind of pressure that proves decisive in producing important movement gains. (Aminzade and McAdam 2001: 44)

Political entrepreneurs use anger to ignite a disproportionate retaliation that serves to clarify, both to one’s own group and to outsiders, who is the perpetrator and who is the victim. Disproportionate reactions reveal the “true face” of the opponent.

Why Anger is an Effective Political Resource

Why Anger is an Effective Political Resource

Why is the creation and enflaming of anger a commonly used and effective political resource? There is a need for more study on this question, but several answers come to mind. First, the cognitive antecedents of the emotion are not that complex— “a perpetrator committed a bad action against us.” The cognitive antecedents of other emotions are more complicated. For instance, the emotion of resentment requires perception of status hierarchy and reversals within that status hierarchy; the basis of fear can be multiple and diffuse; anxiety is more like a mood than an emotion, with murky origins.

Moreover, for millennia, humans have been creating systems of justice with the identification of perpetrators, victims, and specific crimes, and corresponding punishments. Anger transforms individuals into “intuitive prosecutors.” In many societies individuals might not need a big push to take on that role because history and culture have prepared them for it. Today’s popular culture has only reinforced the schema. The perpetrator-victim-anger-justifiable revenge plot is perhaps the most common storyline of Hollywood movies.

Additionally, the B and C effects listed above seem especially powerful in the case of anger. When in the grip of revenge-seeking, individuals do not easily process new information, especially evidence favorable to the identified perpetrator or material that provides complicating context.

Relatedly, the counterstrategies to anger-producing strategies are not often effective. To build from an example above, Iraqi leaders recognized the anger-based strategies of Zarqawi. They appealed to their followers to not give in to their anger. A prominent disciple of Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani told worshippers that “Submitting to one’s passion and confusion will bring us to domestic sedition and eventually lead us to failure. We must go forward, be patient, and carry on building the new Iraq.” (Daragahi 2005) Likewise, political leaders such as Prime Minister Ibrahim al-Jaafari called for a “rational, political” struggle. (Associated Press 2005) Leaders also constantly tried to frame the conflict in terms of “criminal terrorists” versus “Iraqis” in their own effort to create or solidify identities and thus prevent polarization and civil war. These appeals had limited effectiveness. To tell others “don’t be angry” is not usually helpful.

Future Directions in the Study of Anger and Politics

1. The ability of political actors to create clear cognitive antecedents. The existence and level of anger depends on the clarity of the appraisal of the situation and how well it identifies a perpetrator, motive, and victim. On this issue, I would mention some ongoing research on anger by Aidan Milliff, a dissertation student in the Political Science Department at MIT. Milliff conducted in-depth interviews of 32 family members of homicide victims in Chicago. Were they angry? Did they seek vengeance? Milliff summarizes his findings: “Evidence suggests that cognitive clarity about the identity of the perpetrator, the perpetrator’s motive and the nature of the violence as unjust are necessary for an individual to become angry at the perpetrator.” All three elements were necessary for anger to take hold. Even when the perpetrator was known, the victim’s family member was less likely to become angry if they could not piece together a story that included an understanding of motive. (Milliff, unpublished manuscript)

On a wider scale, this finding suggests that political actors who wish to inculcate anger as part of a strategy of provocation need to provide a convincing narrative that includes all of the cognitive antecedents of the emotion. Which political actors can create and instill such narratives? Under which conditions can they do so? In two of the cases above, unsurprisingly, political actors involved sacred places as part of the provocation. Symbol-rich environments would seem to lend themselves to strategies of provocation and anger. When whole populations are emotionally invested in group sites and symbols it is not difficult to enhance and enflame anger through specific attacks. How can such strategies be blunted? If potential provocateurs do not have such symbols as resources will they be unable to use anger as a resource?

2. Separating anger from other emotions. Some studies have found that anger compels individuals to participate in positive types of political behaviors rather than seeking punishment. It is probably true that many intense negative emotions compel people to act in some way, but we need to establish which emotions are really at work. I would argue that we do possess the knowledge and ability to both operationalize specific emotions as variables and to study the sub-mechanisms (the A, B, and C effects) relating to information collection and belief formation that define those emotions. We need to build on the insights coming out of the appraisal tendency approaches to emotion rather than lumping together distinct emotions only similar in valence and intensity.

3. Anger is about actions, not the character of the actors. In this concluding issue, I will pick up on both the last point and the introduction’s remarks on the current state of US politics.

Mentioned just above, political scientists studying emotion should try to distinguish specific emotions at work as much as possible. One key distinction is whether the emotion is generated by appraisals and beliefs about actions, events, or situations, or by appraisals of inherent qualities. This distinction helps separate anger from contempt. Anger, to repeat, is defined by cognition that an individual or group has committed a bad action against one’s self or group; the action tendency is toward punishing that individual or group. Contempt, on the other hand, is not about actions or a specific situation. Contempt follows from cognition that a group or object is inherently inferior or defective; the action tendency (A effect) is toward avoidance.

The B and C effects of contempt have clear political ramifications. Attention funneling prevents the consideration of any positive actions of the targeted group. The fundamental attribution error is prominent. Groups that are the object of contempt become a vehicle for scapegoating. Critically, once one sees an actor as inherently worthless, a change in the situation is unlikely to alter that belief. Contempt does not systematically decay.

For those of us in the United States, we must ask ourselves whether we are living in a time of anger or contempt. Contempt is arguably worse. Contempt can fuel processes of isolation. The action tendency of contempt is avoidance. As noted, in the age of Trump, friends and even family members avoid each other, or at least avoid discussion of politics, so as not to even feel the unpleasant emotion of contempt when views become so polarized. Liberals will not wish to move to the south, conservatives to the northeast. The politics of contempt can create personal and even geographic bubbles. Contempt is usually mutual. Paul Krugman wrote an op-ed before the election about Republican leaders who supported Trump. The title of the piece was “Worthy of Our Contempt.” (Krugman 2016) Undoubtedly many more Democrats, and others, see Republicans as more worthy of contempt now than before the election.

One key issue to study is the relationship between anger and contempt. Clearly, if an actor’s serial actions are repeatedly seen as negative then anger will transform into contempt. Judgments about action will become judgments about character. Americans are often able to separate actions and character. On the recent passing of John McCain, it was common to hear Democrats say that he was a good man although they disagreed with many of his policies. A world in which citizens can separate their emotions about actions from emotions about character might be a more productive political world, one where compromise is more possible. Unfortunately, it would seem that the current trend in emotion-based politics is to try to transform anger into contempt. This effort underlies the politics of polarization. It is a worthy object of further study.

References

Aminzade, R., & McAdam, D. (2001). Emotions and Contentious Politics. In R. R. Aminzade, J. A. Goldstone, E. J. Perry, W. H. Sewell Jr., S. Tarrow, & C. Tilly (Eds.), Silence and Voice in the Study of Contentious Politics(pp. 14-50). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Associated Press (2005, September 14). Iraq Prime Minister Condemns Bombings.

Bodenhausen, G., Sheperd L., & Kramer, G. (1994). Negative affect and social judgment: The differential impact of anger and sadness. European Journal of Social Psychology, 24, 45-62.

Christia, F. (2007). Walls of martyrdom: Tehran’s propaganda murals. Centerpiece(Winter), Center for Government and International Studies, Harvard University.

Daragahi, B. (2005, September 17). Sunni, Shiite clerics press for calm. The Boston Globe.

Franks, D. D., & Gecas, V. (1992). Current issues in emotion studies. In D. D. Franks & V. Gecas (Eds.), Social Perspectives on Emotion: A Research Annual. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Gallagher, D., & Clore, G.L. (1985). Effects of fear and anger on judgments of risk and evaluations of blame. Paper presented at the Midwestern Psychological Association.

Goldberg, J. H., Lerner, J. S., & Tetlock, P. E. (1999). Rage and reason: The psychology of the intuitive prosecutor. European Journal of Social Psychology, 29, 781-795.

Goldenberg, S.(2000, September 28). Rioting as Sharon visits Islam holy site. The Guardian.

Keltner, D., Ellsworth, P., Edwards, K. (1993). Beyond simple pessimism: Effects of sadness and anger on social perception. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,64, 740-752.

Krugman, P. (2016, August 1). Worthy of our contempt. The New York Times.

Lerner J. S., Gonzalez, R. M. Small, D. A., & Fischoff, B. (2003). Effects of fear and anger on perceived risks of terrorism: A national field experiment. Psychological Science, 14, 144-150.

Lerner, J. S. and Keltner, D. (2001). Fear, anger, and risk. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81,146-159.

Lerner, J. S., Li, Y., Valdesolo, P., & Kassam, K. S. (2015). Emotion and decision making. Annual Review of Psychology, 66, 799-823.

Mano, H. (1994). Risk-taking, framing effects, and affect. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes,57, 38-58.

Milliff, A. (2019). Facts before feelings: Theorizing emotional responses to violent trauma.Unpublished manuscript, Political Science Department, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Murphy D. (2006, February 23). Attack deepens Iraq’s divide. Christian Science Monitor.

Newhagen, J. (1998). Anger, fear and disgust: Effects on approach-avoidance and memory,” Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media, 42, 265-276.

Ortony, A., Clore G.L., & Collins, A. (1988). The Cognitive Structure of Emotions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Peters, J. (2018, August 17). In a divided era, one thing seems certain to unite: Political anger. The New York Times.

Petersen, R. (2001). Understanding Ethnic Violence: Fear, Hatred and Resentment in Twentieth Century Eastern Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Petersen, R., & Zukerman, S. (2009). Anger, violence, and political science. In M. Potegal, G. Stemmler, & C. Spielberger (Eds.), A Handbook of Anger: Constituent and Concomitant Biological, Psychological, and Social Processes(pp. 561-581). New York, NY: Springer.

Petersen, R. (2011). Western Intervention in the Balkans: The Strategic Use of Emotion in Conflict. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wong, E. (2006, February 22). Blast destroys Golden Dome of sacred Shiite shrine in Iraq. The New York Times.

[1]See in particular Petersen 2001; Petersen, with Zukerman 2009; Much of this section is taken from Chapter 2 of Petersen 2011.

[2]For a review of appraisal theory see Lerner et al. 2015.

[3]See Lerner and Keltner 2001; Gallagher and Clore 1985; Mano, 1994; Lerner et al. 2003.

[4]See Newhagen 1998. Newhagen found that images producing anger were remembered better than those inducing fear, which in turn were remembered better than those creating disgust.

[5]One of the world’s most famous incidents of “baiting” an opponent into self-destructive retaliation must be Zidane’s head-butting response to taunting during a World Cup final watched by one billion people.

[6]Murphy put the number at 29 while Wong provided a number of 25 mosques “burned, taken over or attacked with a variety of weapons.”