An Interview With Andrea Scarantino (January 2016)

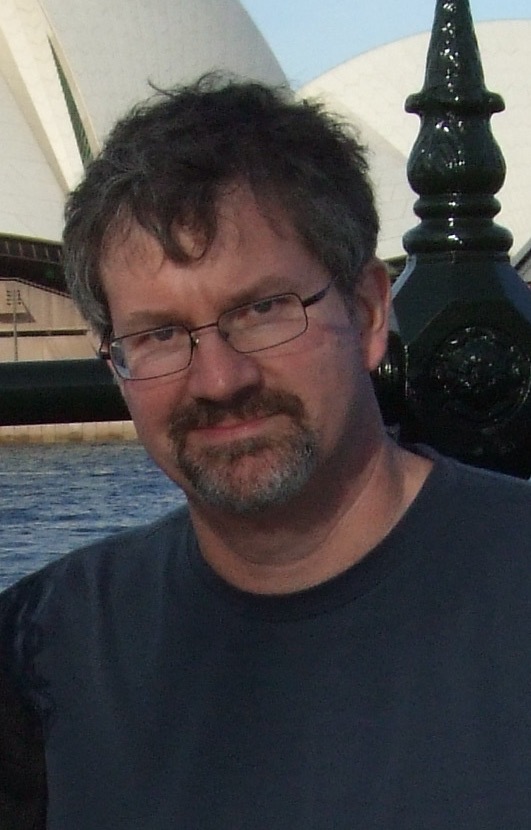

Justin D’Arms is Professor and Chair of the Department of Philosophy at Ohio State University, Columbus Ohio. He has been a recipient of grants from the National Endowment for the Humanities and the John Templeton Foundation, and of fellowships from the Charlotte Newcombe Foundation, the National Endowment for the Humanities, and the Princeton University Center for Ethics and Human Values. His research on moral philosophy, moral psychology and the philosophy of emotions has been published in leading philosophy journals including Ethics, The Journal of Philosophy, Oxford Studies in Metaethics, Philosophical Studies, Philosophy, Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, Philosophy of Science and The Southern Journal of Philosophy, as well as in many collected volumes. He has been a member of ISRE for twenty years, and has also published in interdisciplinary journals and volumes including Emotion Researcher and The Journal of Consciousness Studies.

Where did you grow up? Did your parents encourage your intellectual pursuits? What were your main interests growing up?

I grew up in Ann Arbor, Michigan and Rome, Italy. I loved to read, and my mother was a big influence there. She always had a stack of books to suggest to me whenever I announced I was bored. She is English, and gave me a lot of Victorian books for children or teens that she had read herself as a child. Some of these were pretty weird, in retrospect. I half recommend Hilaire Belloc’s Cautionary Tales for Children in this vein, though your readers might want to vet it first. As I got older she had me reading a lot of Graham Greene and Evelyn Waugh before I could really understand them, but there was plenty of P.G. Wodehouse too. My father got me interested in history from an early age. He took me all around southern Italy to the archaeological sites he was visiting for his work. We had lots of good picnics at old aqueducts and amphitheaters.

You lived in Italy for five years over the course of your childhood. Do you still speak the language? What are your memories of life in Italy? Have you been influenced by this Italian experience in some important ways?

I do still speak Italian pretty comfortably after a day or two in Italy, though it takes a while for some of the vocabulary to come back. The period I remember best was 1977-79, when I was in my early teens, excited to be independent. It was an incredible place to go through that transition—I was really conscious of the beauty and the history of my surroundings. I wandered all around Rome on my own or with friends, going to museums, parks and cafes, discovering ruins and churches, and trying to flirt with Italian girls. I felt very grown up doing these things on my own as a kid in a foreign language and a big city.

That was a great time for me, but it was a difficult time for Italy. No one could form a stable coalition in parliament, and it seemed as though the government fell every few months. There was political graffiti all over Trastevere, much of it fascist, and sometimes violent demonstrations throughout Rome. This was also the era of terrorist attacks by the Italian Red Brigades. They killed Aldo Moro, the former prime minister, and left his body in the trunk of a car in the middle of Rome. I remember one day when I was thirteen or fourteen the police were fighting with demonstrators blocking the tram I took home from school. I had to get out and find a way home around tear gas and people running from rubber bullets. This was very scary, but exciting too. When I think about how we parent in the US today, the difference is striking: it’s amazing to me what I was allowed to experience growing up in Rome in the 70s.

What led you to become a philosopher? Are you happy you did? Would you recommend life in academia, and specifically life as an academic philosopher, to your own children?

I was turned on to philosophy during high school, when I visited a friend who had just started at Harvard, and attended his Introduction to Philosophy class taught by Robert Nozick. One hour in that class and I went to University with at least an inkling that I wanted to study philosophy.

From high school on I tended to be more interested in ideas and arguments than in facts about how things work. I was not terribly interested in science until I started to see it as relevant to the questions I cared about, during graduate school. I managed to avoid learning any chemistry in school, because who cared about how things stick together? In retrospect I very much regret not learning more at the stage in my life when things stayed in memory more easily.

Being a professional philosopher has been a wonderful job for me. I love the things I get to think about, write about and teach. And I love being in a discipline in which, for the most part, I can listen with interest to talks across different areas of specialization and appreciate and engage with them. I also love it that I can talk about my work with colleagues who do not read anything in the areas I work on, and get valuable feedback. These are among the things that make philosophy a great discipline.

I wish I could recommend this path to a next generation, but I think the working conditions for most philosophers are not very good, and even at traditionally strong public research universities like mine, they are hiring fewer tenure track faculty who do research in the humanities. Graduate programs are shrinking and there is pressure to hire adjunct faculty. I would like to think that this is a passing moment, but I don’t.

You got your PhD in philosophy at the University of Michigan in 1995. What did you write your dissertation on, and what were the most significant influences on your philosophical upbringing at the University of Michigan?

My dissertation was entitled “Evolution and the Moral Sentiments.” It defended a sentimentalist approach to evaluative thinking, which I will discuss in more detail in what follows, and an evolutionary understanding of the emotions. My advisor was Allan Gibbard, and I was heavily influenced by his work. But there were a lot of other wonderful philosophers at Michigan at that time, including Stephen Darwall and Peter Railton who were important members of my dissertation committee. I also learned a lot from David Velleman, Elizabeth Anderson, David Hills, and Jim Joyce. Allan and Peter were very naturalistic in their (very different) approaches to metaethics, and encouraged me to make contact with people in other disciplines at Michigan.

At that time, University of Michigan had a very active interdisciplinary research group called Evolution and Human Behavior. I went to all their talks, and most of the influential evolutionary psychologists came through. I also took several classes from Richard Alexander in the biology department, who was great. Randy Nesse from psychiatry was a reader on my dissertation, and a very helpful person to talk with about emotions and evolution. I also benefitted from the terrific people in Psychology at UMich: Phoebe Ellsworth, Dick Nisbett, and the late Bob Zajonc who set me on a useful path in my work on empathy. The late 80’s and early 90’s were a great time to be in graduate school at Michigan.

Your main research interests are in ethics. What sorts of questions do contemporary moral philosophers worry about? What sorts of moral questions are you most interested in?

In the broadest sense, ethics is about the question of how to live. I mean that very broadly, so as to include questions about what to do, what to think, what to want, and what to feel. Ethical judgments are thus practical in two senses. They concern practice—what to do with your actions and attitudes. And these ethical judgments make a practical difference— at least to the extent that our actions, thoughts, desires and emotions are responsive to our conclusions about reasons in favor of or against them. It is partly a psychological question to what extent these actions and attitudes are responsive to ethical judgments. But it is partly philosophical too, inasmuch as it is not just an empirical matter to determine which judgments and attitudes to count as “moral.”

Much contemporary discussion in moral philosophy is concerned with debates over what are the fundamental normative concepts. Some think the concept of a reason is basic. Some think ought is basic. Some think rationality is basic. And there are various views about the relations among these. Another big topic is how to understand various apparent norms of rationality, such as a putative rational requirement to do what you believe is necessary in order to achieve your ends or goals. And moral philosophy tends to have a special interest in moral judgment in particular, which is a narrower subject than ethics. Moral judgment concerns the notions of moral obligation and moral right and wrong.

I have been working more on value and ethics in general than on the narrower questions about moral obligation, and right and wrong. Among other things, I am interested in questions about the relationship between psychological facts and ethical judgments. Here are a few: What kinds of psychological states correspond to a person’s reaching an ethical conclusion about what to do or an evaluative conclusion about what is good or bad in various ways? How do psychological facts about what people want and feel bear on questions about what they should do? How responsive are various different kinds of attitudes and other psychological states, including emotions, to different kinds of ethical and evaluative judgment? (It is sometimes suggested that ethical judgments are largely idle—that they are just post hoc rationalizations of “alarm-like” emotional responses. I think that is false, though it springs from overstating a grain of truth.)

You have had a long lasting and very fruitful collaboration with philosopher Dan Jacobson from the University of Michigan. Why did you decide to start working together, and have continued doing so over the past 20 years? Do you find it easier to write with Dan than alone at this point? Is there a secret to a successful and long-term intellectual collaboration?

Dan and I were friends before graduate school and we talked about philosophy a lot from the time I arrived in graduate school. Our first joint paper came out of a reading group that we were in together while working on our dissertations. What had initially seemed like a small point got more complicated as we talked it through, and eventually led to a co-authored article:“Expressivism, Morality, and the Emotions” Ethics 104 (July 1994): 739-763.

Working with Dan is great. What I like most about philosophy is thinking and talking it through with someone in a collaborative spirit. And I love talking philosophy with Dan in particular. I think the fact that we started while we were in graduate school made this easier, because we were both at formative stages in our philosophical thinking, and were being influenced by a lot of the same people and ideas. So we started with a common stock of background knowledge and some shared assumptions—some of which we subsequently came to question in mutual discussion.

I would not say that it is easier to write together, though. Writing goes slower when you have to form a group mind about it. And of course over the years we’ve had other different influences and come to see some things very differently. But collaborative work remains especially gratifying and enjoyable. I feel very lucky to have such a great collaborator and such a good working relationship.

In a number of influential publications, Sarah Brosnan and Frans de Waal have argued that non-human primates are inequity averse, at least in the sense that they expect equal pay for equal work. In a ‘token exchange’ experiment, capuchin monkeys were shown to reject a lower quality reward (a cucumber) if their cage neighbor was given a higher quality reward (a grape) for the same work they did. Do you think that the human sense of justice is an evolutionary adaptation from this sort of primitive inequity aversion?

No, I don’t, although I have not followed the discussion of these studies closely. My impression is that some follow-up studies have called into question whether inequity aversion per se is the best explanation of what is going on. But in any case, from what I know of it there seems to me to be a problematic conflation going on here. I am sure that various relevant tendencies in our primate relatives are homologous to some tendencies in our own psychology.

But I don’t think that this is a good way of thinking about the evolution of justice. Anger or frustration at not getting what one saw someone else get is entirely compatible with having no interest in equality at all, much less in justice. A question that would go closer toward seeking an explanation of justice is why we are interested in patterns of distribution in ways that go beyond a concern for our narrow self-interest. (Why are we concerned about other people getting equal pay for equal work, for instance?)

Let me offer an analogy. There is a good adaptive explanation for why various animals, including us, care about the well-being of their offspring. Human concern for our offspring is surely caused in part by an evolved psychology some of which we share with other primates and some of which we share with other mammals too. It’s also true that we humans moralize parental obligations. We think we and other people ought to care for our offspring. But is the human sense of parental obligation an evolutionary adaptation from the primitive impulse to care for one’s young? I think that would be an unhelpful way of thinking about it, because it misses what is interesting about adding a moral dimension to a pattern of behavior.

Explaining why we moralize child-rearing seems to require something very different from explaining why we are moved to care for our children. Among other things, it requires explaining why other unrelated people are prepared to invest any interest or resources in sanctioning me if I fail to properly care for my children. What needs explaining is why, over and above generic tendencies to invest in offspring, we have superimposed moral requirements. (I am not saying that this is terribly mysterious—my point is just that this moralization is a separate thing that should get a separate explanation.)

It is quite common for people thinking about the evolution of morality to conflate evolutionary explanations of behavior that we also have moral convictions about with evolutionary explanations of our having those moral convictions. I made some of these points a while ago in some papers about certain evolutionary game theoretic explanations of justice that I think had similar problems. Consider a simple bargaining game, described by John Nash. Two players must divide a cake. Each submits a demand for how much to claim. If their claims sum to more than 100% of the cake, neither gets anything. If they sum to 100% or less, each gets what she claimed.

Brian Skyrms showed with some elegant modeling that if you start with a mixed population of different strategies, and you allow strategies to reproduce according to their payoffs, then many (but not all) populations will evolve toward the tendency to demand half the cake. Skyrms called this equilibrium “share and share alike” and suggested that it might be the beginning of an explanation of justice. But if demanding half evolves in a population because it pays best, then it does not need the backing of any social sanctions. It does not need to be moralized. [for more, see “Sex, Fairness and the Theory of Games” Journal of Philosophy 93 (December, 1996): 615-627. And “When Evolutionary Game Theory Explains Morality, What Does it Explain?” The Journal of Conciousness Studies 7:1,2 (2000) 296-300].

I think that the evolution of justice is best thought about not just in terms of the evolution of tendencies toward certain patterns of behavior. We need to be looking at the psychology underlying the behavior—specifically at the psychology that explains our tendencies to accept and abide by certain kinds of social norms. But even that is not enough, because some social norms are not moralized—for instance because they are treated as merely conventional So an evolutionary explanation of justice, I think, should be investigating our tendencies to back those norms with sanctions of particular sorts. An important difference between moral norms and other social conventions has to do with how we treat violations. Violations of justice are subject to punitive psychological responses, whereas violations of other social norms that are superficially similar will be subject to quite different responses—such as social withdrawal. I believe that there probably are relatively discrete psychological structures that are there because they assist in reciprocal norm enforcement. And I think that this must be because these structures were advantageous to the individual—not just to groups that had norms of reciprocity.

I think the token exchange experiment and the literature surrounding it are very interesting. But more would need to be shown before we treat wanting to get some salient reward that others got as a proto-moral concern. We should not be too impressed by the simple fact that the reward rejected is unequal (if indeed that turns out to be the causally relevant feature). Unless we can see the primate’s frustration or disappointment as connected to norms to which the rewarder is somehow being held accountable, I don’t think we are dealing with anything like justice.

You have been articulating for several years now, in collaboration with Dan Jacobson, an influential research program in the philosophy of emotions labeled Rational Sentimentalism, which is also the title of your forthcoming book with Oxford University Press. Could you briefly explain what Rational Sentimentalism tries to explain, what are its fundamental tenets and what are its main alternatives?

Some very familiar evaluative concepts clearly depend in some way on emotional responses. Call them “sentimental values.” These concepts include funny, disgusting, shameful, and fearsome. These are evaluative concepts because thinking that something is funny or shameful is thinking it is good or bad in some way. They are sentimental because the particular ways in which they evaluate things as good or bad have to be understood by way of amusement, shame and so on. Rational sentimentalism aims to explain these sentimental values through understanding their dependence on the relevant underlying emotions.

According to rational sentimentalism, sentimental values are response dependent, and the emotional responses on which they depend are conceptually and explanatorily prior to the values. So we claim that the concepts of being funny and shameful depend on amusement and shame, not vice versa. Likewise for danger and fear—the category of dangerous things is constructed because of the human propensity to fear. Danger is not an explanatory category independent of our emotional responses (for reasons I explain later).

These concepts arose because we humans are prone to those emotions and find ourselves thinking and talking about what things are and what things aren’t proper objects of amusement, fear and shame. But these are not just judgments of psychological or sociological fact, about what the speaker or the community tends to be ashamed of, or afraid of. The temptation to interpret evaluative judgments as judgments about the dispositions of a speaker or a community is understandable, but misguided. It is understandable because it offers a clear meaning for these evaluative judgments. If judgments about shamefulness were about what people tend to be ashamed of, there would be ways of measuring when they were correct—and that would be nice, especially to social scientists. But if they were about those questions, then they would not be disputed in all the ways that they actually are.

For instance, when people disagree about whether something like backing down from a fight is shameful, their dispute is not normally an empirical matter, but a disagreement over how to feel about things. They are not arguing about whether they themselves, or some social group or culture, tend to be ashamed of such behavior. They are arguing about whether it is something to be ashamed of. As I would put it, the dispute is best understood to concern whether shame is a fitting response to backing down.

And that is not a question that the disputants would take to be settled by facts about peoples attitudes, not even their own. (If that sounds odd, consider a teenager who has become convinced that being gay is no worse than any other sexual orientation, but who still feels deeply ashamed of his homosexuality because he lives in a family and society that condemn it. He thinks it is not shameful, but this is not an empirical claim about how he or his culture feels. It’s a view about whether this is something to be ashamed of—whether shame is fitting.)

So, according to Rational sentimentalism, judgments of what is and isn’t funny or shameful are best understood as devices of emotional regulation. They are about, roughly, what to be amused by or ashamed of. Notice that is a perfectly reasonable topic, and something that it is very much worth discussing and trying to agree upon, even if it is not a matter that can be settled by a survey.

Sentimental values are special because they are tied to emotions that are part of the common human repertoire. These emotions need not be “basic” in various senses—they may be quite complex, open programs in terms of their elicitors, and they need not issue in stereotypical behaviors. Jacobson and I believe that there are some pretty complex pancultural emotional types, including all the examples I have been using so far, and others such as disgust, envy, anger, pride and regret. The fact that these emotions are pancultural ensures that all human beings are invested in their paired values—they are not culturally specific or parochial values. Of course, different cultures and different individuals have different standards of what is shameful, funny and so on.

But the panculturality of shame ensures that these different standards are competing answers to a common question: what conditions or circumstances give one reason to feel and be moved by this specific syndrome of urgent withdrawal, felt social inferiority, motivation to eliminate or conceal the offending trait, and so on. So sentimental values are universal human values, in an important sense.

Of course it is possible to adopt various kinds of philosophical skepticism about sentimental values, but that is true about all values. At least in the seminar room, one can doubt whether anything is truly shameful, or funny, or outrageous, just as one can doubt whether anything is really rationally or morally obligatory. But these sorts of theoretical doubts can be hard to internalize in your life and choices. And in some respects it is even harder to adopt that skepticism as a practical matter about the sentimental values than about morality, for instance. Because of their link to emotions that will be with us whatever philosophical positions we adopt, sentimental values have a special kind of import to us all. So I doubt that any philosophical skeptic can stop using these sentimental value concepts, because of the role they play in regulating and making sense of one’s emotional life. In other words, sentimental values can’t be fully shrugged off in the way that many philosophers have thought various other values can be.

You have described the moralistic fallacy in your work with Dan Jacobson. Can you explain what that is and why it is important?

The moralistic fallacy is the mistake of supposing that reasons why it would be morally good or bad to feel some emotional response toward an object bear on whether that emotional response is fitting (i.e. on whether the object has the particular evaluative feature that it seems to you to have when you are feeling some particular emotional response toward it). For example, suppose you think it would be bad to be amused by a cutting joke made by some wit at the expense of your friend. You think that a good friend should be angry, not amused, at this quip. If you concluded on that basis that the joke was not really funny, that would be an instance of the moralistic fallacy. Maybe it’s funny, maybe it isn’t, but your moral reasons not be amused by it are irrelevant to that question. Or suppose you have to clean a disfiguring wound on a young soldier. It would be better not to be disgusted by it, for his sake. But that does not diminish how disgusting it is in the least.

The moralistic fallacy is important in two different ways. One is that people actually make mistakes of this sort surprisingly often in thinking about various values. Such mistakes show up in the work of philosophers, and in casual conversations about grounds for amusement, anger, envy and jealousy. People think that it is bad to be envious, and conclude that envy is unfitting—that there is some error in the idea that other people having something can be bad for you, as it seems to be when you are bothered by in the way characteristic of envy. But even if it is bad to be envious, it does not follow that you are not made worse off when your rival gets some award. And this is what would need to be shown in order to show that envy was not merely ugly but mistaken, or unfitting.

Similarly, even if it is better to turn the other cheek than to be angry, it does not follow that you have not been transgressed against in a way that makes anger fitting. Accusations of irrationality or unjustifiedness of emotions are often based on these sorts of moral views about the emotion. Sorting out the difference between moral complaints about emotions and complaints that are more internal what the emotion itself is concerned with is important to appreciating different kinds of evaluative issues that run through all our lives.

Similarly, even if it is better to turn the other cheek than to be angry, it does not follow that you have not been transgressed against in a way that makes anger fitting. Accusations of irrationality or unjustifiedness of emotions are often based on these sorts of moral views about the emotion. Sorting out the difference between moral complaints about emotions and complaints that are more internal what the emotion itself is concerned with is important to appreciating different kinds of evaluative issues that run through all our lives.

Another reason the moralistic fallacy matters is a little more in-house. It has to do with a popular class of philosophical theories of value. So called Fitting Attitude theories try to understand being valuable in terms of the idea that to be valuable is to be the fitting object of some kind of evaluative attitude. (That is what Rational Sentimentalism says, too. RS is a kind of fitting attitude theory that focuses specifically on emotions rather than other types of evaluative attitude.) The moralistic fallacy creates a problem for all fitting attitude theories, which is a special case of what has come to be called the Wrong Kind of Reason Problem. A standard example concerns admiration, which might be an attitude rather than an emotion. For a person to be admirable is for admiration of him to be fitting, for instance.

People used to think that this idea of fittingness could be cashed out in terms of some simple normative notion. So for instance A.C. Ewing did it in terms of “ought”—he analyzed ‘good’ in terms of what you ‘ought’ to have some sort of pro-attitude toward. More recently people have been trying to do it with the idea of there being ‘reasons’ for the relevant attitude. The moralistic fallacy shows that these proposals won’t work without some extra materials, because there can be moral reasons against being amused at the joke that do bear on whether you ought to feel it, but do not bear on whether the joke is funny. (Similarly, there could be moral reasons for admiring your child’s musical performance—he needs your sincere admiration—that do not bear on how admirable it is.)

This means that Fitting Attitude theories need a way of saying what kinds of reasons bear on the fittingness of attitudes. And they need a way of doing this without appealing to the values they are trying to explain, on pain of making the theory circular. If you want to explain being shameful by appealing to the fittingness of shame, you had better not explain reasons of fit for shame by saying that they are the ones that bear on whether the thing you are ashamed of is shameful. So Fitting Attitude theorists need to say more about what kinds of considerations are reasons of fit for shame, admiration and so on without appealing to the values we aim to explain. Dan and I have some suggestions about this in the book we are working on. Our initial discussion of the moralistic fallacy is in “The Moralistic Fallacy: On the “Appropriateness” of Emotions” Philosophy and Phenomenological Research LXI No. 1 (July 2000): 65-90.

Do you see any areas of overlap between your work on Rational Sentimentalism and standard debates in affective science? More generally, in what ways can the work of philosophers of emotions be of relevance to affective scientists?

Of course philosophers have been learning a lot from work in the affective sciences over the last thirty years or so. I also think there are many ways in which the work of philosophers is relevant to affective sciences, both with respect to theory construction and assessment, and in raising further possibilities for empirical study. I will say a little about an area in which I think that my own work is relevant.

I discussed this a bit in my lecture at ISRE 2015 last summer in Geneva. It concerns relationships between emotions, appraisals and what Richard Lazarus called “core relational themes.” Sentimentalists like me argue that various evaluative concepts are response-dependent—they must be explained by appeal to emotions. But certain strands of thinking in psychology sometimes seem to want to adopt the opposite direction of explanation. They want to suggest that we should explain the occurrence of various emotions by appeal to appraisals that are (typically said to be) temporally prior to the emotion—or at least to those elements of an unfolding emotional episode that the appraisal supposedly explains.

I discussed this a bit in my lecture at ISRE 2015 last summer in Geneva. It concerns relationships between emotions, appraisals and what Richard Lazarus called “core relational themes.” Sentimentalists like me argue that various evaluative concepts are response-dependent—they must be explained by appeal to emotions. But certain strands of thinking in psychology sometimes seem to want to adopt the opposite direction of explanation. They want to suggest that we should explain the occurrence of various emotions by appeal to appraisals that are (typically said to be) temporally prior to the emotion—or at least to those elements of an unfolding emotional episode that the appraisal supposedly explains.

As I understand it, appraisal is supposed to be an emotion-independent psychological event that provides substantive theoretical understanding of what that emotion is in light of what causes it. I have no objection to this general idea. But it can get problematic depending on how you understand what an appraisal is, and in particular on whether you pack evaluative content into it. It’s when appraisals are understood evaluatively that I think appraisal theory gets into trouble. Let me elaborate.

Readers of Emotion Researcher know that appraisal theories are various, and often appeal to many different kinds of appraisals. There are some very basic kinds of appraisals, like whether some motion in the environment has an agential (which sometimes just means ‘animate’) cause. Then there are appraisals that relate what is going on to the subject’s background beliefs and aims—such as ‘novelty’ and ‘goal congruence.’ I have no problem with any of these sorts of ideas—of course some interpretation of stimuli, and some sense of their relation to the organism, has to be part of the explanation of the onset of various emotions.

Notice that in each of these cases, the thing that is putatively being appraised—the cause of the emotion eliciting event, or how that event relates to her goals, or whether she has seen it before—is a factual matter the occurrence of which can be fully understood and explained in emotion-independent terms. And that is part of what makes these claims informative, empirical and falsifiable. But talk of ‘appraisal’ is ambiguous, and psychologists sometimes suggest that the value assigned to the stimulus, the particular way in which it is taken to be good or bad by someone who is proud or ashamed, angry and so on, is itself a prior cause of emotions. This entails that these evaluations can be understood independently of the character of the emotions themselves. I think that in many of the central cases of emotion, this is a big mistake. It imports a lot of commitments that I don’t think are well thought through, or ultimately defensible. The distinction between evaluative and prosaically factual appraisals is an area where I think the philosophical literature is much better developed than the psychological literature.

So, for instance, lots of psychologists cite Lazarus approvingly for analyzing emotions as involving core relational themes that are a kind of evaluative interpretation of environmental stimuli. Lazarus seems to have thought that in order to get into a given emotional state, one must first “gestalt” the object in terms of one of his core relational themes. To be afraid of something one must first appraise it as an “immediate, concrete and overwhelming physical danger;” to feel guilt for something one did one must take oneself to have “transgressed a moral imperative,” and so on.

Notice that in order for these to be the informative and substantive proposals that they appear to be, you have to think that appraising something as a transgression of a moral imperative, or an immediate physical danger, is a state that can be fully explained without appeal to the emotion it elicits (and, perhaps, that it is a necessary precursor in order for the emotion to be elicited). But when you start trying to explain the content of those evaluations, this turns out to be highly questionable. It is not at all clear what thoughts of moral transgression are about—this is a debated question. One venerable view on the matter is that their content depends essentially on moral sentiments, including guilt. If that is true then Lazarus’s proposal would be highly problematic. Maybe it is not true, but the point is that this is a place where the psychology of emotion is making a bet on the content of moral concepts that its practitioners seldom seem to appreciate.

To see this, suppose that the best theory of morality were a sentimentalist theory according to which the concept of moral transgression is explained as “action befitting guilt.” If that were true, then an appraisal theory of guilt in terms of moral transgression would be no more informative than an appraisal theory of disgust that said that disgust requires an appraisal of something as disgusting, or a theory of surprise that says surprise involves a surprisingness appraisal. Notice that while there are a great many appraisal theories, no psychologist to my knowledge has ever offered such a proposal.

Why not, you might ask? Presumably because no one thinks that would be a substantive and interesting theory that told us something important about the nature of surprise or disgust—it would be too circular. I am suggesting that Lazarus’s theory of guilt might be equally unsubstantive, and that whether it is or not hangs on a philosophical question about the concept of moral transgression. So appraisal theorists who want to be making interesting, substantive proposals (not circular ones) need to pay attention to the concepts they invoke in describing their appraisals.

Can you say a bit more about how the problem extends to fear, which does not seem to have a content that depends essentially on moral sentiments?

I do think Lazarus’s proposal about fear runs into a problem along similar lines. Either “immediate concrete and overwhelming physical danger” turns out to be tacitly response-dependent (and thus not the substantive restriction it aspired to be), or it’s demonstrably false that you need to appraise something that way in order to be afraid of it. Demonstrating that takes a long argument, so I will just gesture at part of it. [Interested readers can find a longer version of it online here: http://peasoup.typepad.com/peasoup/2014/02/featured-philosophers-darms-and-jacobson.html.]

The basic thoughts are these: first, Lazarus’s talk of ‘physical’ danger is either empty or mistaken. People can be very afraid that their infidelity will be discovered or that a cybercriminal has accessed their bank account but if those count as physical dangers then we need to remember that physical dangers are not restricted to anything like bodily damage. And, people can be terribly afraid that they will go to Hell for something they have done. So probably we should just agree that fear does not require an appraisal of a physical danger at all.

What about “immediate, concrete, and overwhelming”? That sounds like it is supposed to impose some substantive restriction, but I am not sure what the restriction is, really. People seem to be capable of fearing a lot of different sorts of harms, including some that are pretty unlikely or pretty far off. Moreover, and perhaps more surprisingly, I don’t even think the basic idea that fear requires an appraisal of danger is the substantive claim it appears to be.

Once we recognize the great range of things that people do actually fear, we need to wonder what the concern for ‘dangers’ is really about. You can choke on a cherry. So is eating cherries dangerous? A madman can assault you on the street. Is it dangerous to go outside? If you say yes to these sorts of questions then the concept of danger is trivialized, because everything now counts as dangerous; so the right answer would seem to be no. In order to be dangerous a prospect has to be not just harmful, but sufficiently likely and sufficiently bad. But how bad does a harm have to be, and how likely does it have to be, in order to count as a danger? And how immediate does the prospect of its occurrence have to be? It’s not just that these questions don’t have sharp answers. It’s that it’s not even clear what they are about until you remember that we are creatures who fear things and who are capable of thinking about what it makes sense to fear. Without a sense of fear, we would have no interest in categorizing things as dangerous or not, I suggest.

A rational but emotionless alien might be pretty puzzled by our concept of danger. He would see the point in talking about harms, and the probabilities of their occurrence, but he’d wonder why we want to privilege some specific threshold of expected harm as especially salient. He thinks it’s rational simply to adjust one’s actions smoothly to their expected values, ordering them in a way that maximizes the satisfaction of one’s preferences over time. From that point of view, the concept of danger looks to be an arbitrary and irrational one—drawing a bright line somewhere on a continuum of risks that ought instead to be treated as the continuum that it is.

A rational but emotionless alien might be pretty puzzled by our concept of danger. He would see the point in talking about harms, and the probabilities of their occurrence, but he’d wonder why we want to privilege some specific threshold of expected harm as especially salient. He thinks it’s rational simply to adjust one’s actions smoothly to their expected values, ordering them in a way that maximizes the satisfaction of one’s preferences over time. From that point of view, the concept of danger looks to be an arbitrary and irrational one—drawing a bright line somewhere on a continuum of risks that ought instead to be treated as the continuum that it is.

So I doubt that there is a sensible, emotion-independent notion of danger that can be used to explain fear. And if that is right, then the claim that fear involves a danger appraisal is not the substantive, falsifiable claim it appeared to be. It is more like the suggestion that disgust involves appraising something as disgusting—which might be true but is not the sort of claim the appraisal theorist seems to want.

I would argue, instead, that the concept of danger is really about where to set the thresholds for fear—thinking something dangerous is best understood as thinking that it merits fear—that it is fitting to fear it. That is not to dismiss talk of danger at all. There is a real question to be discussed when deciding whether the probabilities of concussion associated with heading the ball in soccer make it dangerous for children. Even once people agree about the probabilities and the damages, they can disagree about whether the numbers are large enough to count as dangerous. But what those disagreements amount to is fundamentally a question about fear, not some fear-independent appraisal. They are disagreements over what merits the syndrome of attention, control precedence, action tendencies and prioritized goals that are characteristic of fear.

Competing views about what’s dangerous in such cases are best understood as competing attempts to regulate fear with standards that apply to both parties. So we should not think that we understand fear better when we say that fear requires an appraisal of something as dangerous. Instead we should understand appraisals of danger to be assessments of something as meriting fear. Of course it is possible that I am wrong about all that. But the more general point is that psychological theorizing about fear that takes the idea of a danger appraisal for granted is risky, and likewise for a range of other evaluative appraisals. Such claims are at risk of being trivial in ways that are not immediately obvious. Determining whether they are trivial or are instead the substantive, falsifiable proposals they aspire to be requires getting clearer about the terms in which the appraisals are described. I think that more engagement between philosophers who think about evaluative concepts and psychologists who think about the role of evaluative thinking in affect would be salutary.

That’s helpful, thank you. Do you see other points of contact between your philosophical work and the concerns of contemporary affective scientists?

I do. The topic of emotion regulation has been gaining lots of traction in affective sciences lately, and this is something I have interests in as well. Much of the extant literature is about regulating emotions for utility—whether to feel better, to feel emotions that motivate adaptive behavior, or to get along better with others. James Gross’s paper “Emotion regulation: Affective, Cognitive and Social Consequences” (Psychophysiology, 39 2002, 281–291. Cambridge University Press) is a good entry point into this literature, which looks at many different ways in which people can regulate, most of which assume some sort of utility-based goal for the different forms of regulation.

I am interested in some other kinds of regulation that are not regulation for utility. In particular I am interested in emotional regulation by values. Let me explain what I mean by that. [I discuss these issues further in a recent paper: “Value and the Regulation of the Sentiments” Philosophical Studies Vol. 163 (2013)]

You might be better off if you were not ashamed of anything. Or you might be better off if you were ashamed of some things that you are not ashamed of—perhaps because other people are contemptuous of those things and a bit of shame would make you more likely to conceal them and thus to avoid certain social costs. Of course those considerations of utility matter to what steps it makes sense to take in order to regulate your shame. But most of us also have an independent interest in being ashamed only of those things that we think are actually shameful.

Moreover, it matters to us to be ashamed of those things—not to be shameless under all circumstances. At least I think it does—it certainly matters to me. So I, at least, have an interest in regulating my shame not just on the basis of what is best for me, but on the basis of what is shameful by my own lights. This is one version of what I am calling regulation by values.

It also matters to me to be right about which things are shameful—I want to be ashamed of the things that are actually shameful, not ones that I mistakenly think shameful due to social norms that would not stand up to scrutiny. So I am interested in having an emotional sensibility that is sensitive to good reasons for feeling some ways rather than others. In other words, I am interested in trying to see to it that my emotional sensibilities, or perspectives, are not mistaken—that the things I am prone to be ashamed of are shameful. This is a second kind of regulation by value. (Compare two regulative issues for a cooling system: 1) Does the system succeed at maintaining the target environment at the system’s set point? 2) Is the set point that the system is trying to maintain correct—i.e. is it set to the right temperature?)

These points raise several questions that are ripe for more study. To what extent are people in general concerned with regulating their emotional responses for value in either or both of these ways? I would love to see more empirical work on that question. And, how effective is such regulation? In particular, how effective is ethical reflection on the norms that one has internalized in changing a person’s propensities to shame? I know of some work on this topic, by Jonathan Haidt and his collaborators, that takes a pretty pessimistic view of the prospects for thinking to unseat affective tendencies. (Haidt, J., & Bjorklund, F. (2007). Social intuitionists answer six questions about morality. In W. Sinnott-Armstrong (Ed.), Moral psychology, Vol. 2: The cognitive science of morality (pp. 181-217). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.) But their evidence for this claim is very limited, and the main part of it (Haidt’s “dumbfounding” studies) has been widely criticized on a variety of methodological grounds.

Shame is just one example of regulating by values, and we can think of all of the questions I have been raising above in more general ways. We can ask about the regulation of fear—to what extent can we shape it so as to make it more responsive to what we think about dangers? We can also ask how widespread, and how effective, the phenomenon of regulation by value is across the range of affective states. And I think some cross-cultural comparative work on this topic would be very interesting for building a general theory of different kinds of emotion regulation.

In my own case, regulation by values plays a central role across a broad range of emotions. For instance, I am even interested in being amused and disgusted by the right things—things that are funny or disgusting, respectively. In this respect I may be more unusual—this may be a kind of gourmet sensibility. But that too is an empirical question—to what extent people care about having fitting feelings with respect to amusement, disgust, and other feelings that are (typically) more aesthetic than moral. Note that regulating one’s amusement for funniness is quite different from regulating it for utility. Of course one can do both, but they sometimes compete.

Reflecting on how amused you were by the boss’s joke at the party, you might realize in retrospect it was not that funny. Your amusement was adaptive. It need not have been insincere; it’s just that in retrospect you realize that the joke was pretty weak. In one way you might be disappointed in yourself—feeling that you ought to be more discriminating. In another respect, though, you could be glad that you reacted as you did, insofar as your sincere amusement pleased your boss.

You have written on empathy, envy, and regret. Why did you get interested in these emotions in particular? How do you define them? Do you think empathy is always good and envy and regret always bad?

The way that I think about empathy is not as an emotion but as a way of acquiring various different emotions. I define mechanisms of empathy as ones that function to influence the emotions of one person—the observer—so as to produce some kind of congruence between these emotions and those of another person—the model. To say that someone is empathizing with another person, then, is to say that she is being influenced by such a mechanism. Some empathy involves perspective taking, including simulating the model’s position and thereby coming to feel from, as it were, her perspective—this is the kind of empathy most philosophers have been interested in. But other empathic mechanisms involve contagion—catching the emotions of others, for instance through unconscious mimicry and feedback.

My interest in empathy came from the idea that, as a general matter, emotional responses to the world are better informed to the extent that the subject has actual or imaginative acquaintance with a variety of different humanly possible ways of feeling about things. If you are acquainted with what it is like to offend someone accidentally, and also acquainted with what it is like to be offended by someone who did not intend to offend, your responses are to that extent better informed than they would be if you have only inhabited one of these perspectives.

I argued (“Empathy and Evaluative Inquiry” Chicago-Kent Law Review: Symposium on Law, Psychology and the Emotions 74 No. 4 (2000): 1467-1500) for the somewhat surprising thesis that emotional contagion creates pathways to evaluative knowledge that simulation can’t, by playing a positive role in developing better informed emotional sensibilities. Bringing your own sensibility to bear on someone else’s circumstances through simulation limits the range of possible responses you could have to the ones that your sensibility would generate in those conditions. If you would not be offended, in her circumstances, then you will not know what it is like to be her in her circumstances simply by simulating.

Whereas contagion gives you vicarious access to the sensibilities of another, and that opens up some novel possibilities. You can feel what it is like to be offended by something that you yourself would have shrugged off, for instance. Appreciating that can put you in a better position to think about whether the treatment merits offense—whether it is really offensive. That’s not to say that either simulated or vicarious empathy is always good, of course. It can generate ugly or unjustified responses too.

Now to envy. I understand envy as an aversive emotion that focuses the envier on something that a rival has, and motivates the envier to outdo or undo the rival’s advantage. I suspect that this is a natural emotional kind that will prove to be a pancultural emotional syndrome involving some of the classic Frijdan features of control precedence and goal prioritization. One result of thinking about envy in this way is that some of what gets called envy is left out.

Some people say that they envy someone’s house when all they mean is that they wish they had such a nice house. If it doesn’t pain you that he has it, it is not envy in my sense. And if you would not feel better were he to lose it, even though you gained nothing, then it is not envy. That’s not to say that everyone who envies would actually take steps to destroy the rival’s advantage, or even that they must experience a desire to do so. But that’s because well-socialized people don’t act on all their motivations, and sublimate some of them.

So understood, envy is essentially rivalrous, and it only seems to make sense insofar as positional goods like status matter. Put in terms of fittingness, envy is fitting only if the difference in position or possession between the envier and the rival is bad for the envier. Some philosophers think that positional goods don’t matter, and thus that envy is never fitting. But I find that hard to believe. If it were really true that positional goods don’t matter, then it would not matter to be the best, or among the best, at anything. I think that we should accept that positional goods are of value for humans, and that envy can sometimes be fitting.

I grant that, on the view I am offering, envy is somewhat morally unattractive. It involves being bothered by what other people have, not for moral reasons but for competitive ones. And it involves a desire that others lose something even if you get nothing else as a result. That’s ugly. But just because envy is morally ugly does not mean that it is unfitting: it does not mean that the envier is making a mistake in feeling that the rival’s position is bad for him. To infer the unfittingness of envy from its ugliness would be another example of the moralistic fallacy! I actually made a couple of these points in an old issue of Emotion Researcher, dedicated to “Nasty Emotions.” A somewhat less opinionated discussion of the topic is my entry on Envy in the online Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

The work I have published on regret, with Dan Jacobson, relates to its connections with rational choice. We are focused on the emotion that is directed at one’s own past action and involves tendencies to chastise oneself for a mistake and form intentions to act differently in like occasions in the future. Is regret bad, so understood? I don’t think so. Rudiger Bittner has argued, following Spinoza, that regret in this sense is always “irrational” because there is no point in adding the further misery of regret to the costs of one’s error. But even if that were true, there is an important respect in which regret would make sense when in fact one has made a mistake—it would be a fitting reaction, even if an unfortunate one. Moreover Bittner’s claim is surely not true. In fact. he offers no evidence for his assumption that we could learn from our mistakes just as well without the reinforcement of regret. I suspect this Stoic idea of a regret-free existence would be a recipe for disaster for human beings.

Dan and I were interested in the question of whether and how the (correct) anticipation of potentially irrational regrets affects the rationality of choices. Suppose you face a choice situation where the expected value of options A and B are (as nearly as you can tell) tied on the merits. But option A is also such that if you don’t choose it, you know you will regret that (reasonably or not), whereas option B is not like that. This could be because A is a once in a lifetime opportunity, but it’s quite unclear whether you will actually enjoy it. (For me, the prospect of a trip to work with a marine biologist friend collecting specimens for a month on a South Pacific atoll had these features, but obviously these things are personal.) Whereas B offers lots of predictable but familiar goods. The question is, if the options seem to be otherwise tied, all things considered, does it make sense to let the anticipated regrets swing the balance in your decision?

Suppose that you think it can make sense, as we do. Then the funny thing is that the regrets become self-justifying. For consider: I stipulated that the options are roughly tied, on the merits. This means that neither would be a mistake. So it seems that it does not make sense to feel regret, whichever choice you make. But I also stipulated that as a matter of fact you know you will feel regret unless you take option A—it is just that kind of case. So far, then, we are just anticipating a predictable but unjustified feeling. Predictable but unjustified feelings are common, like the tendency to blame the messenger or to be embarrassed even by positive social attention.

But now consider that, if the options were tied on the merits, and we then add in the regret you will predictably feel if you forego option A, then it seems that it actually becomes better to take option A than option B after all. So it would be a mistake to take B after all, and you would be right to regret choosing it, if you did! This means that the predictable regret justifies itself, in a sense. Were it not for the fact that you know you would feel it for choosing B, you would have no reason to prefer A. But since you do know you will feel it, it really is a mistake to choose B, and thus the regrets you will feel are fitting after all.

We use this argument as a springboard into further discussions of how regret can make actions choiceworthy or mistaken in our paper “Regret and Irrational Action” in David Sobel and Stephen Wall, eds., Reasons for Action, , eds. (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2009) pp. 179-199.

Has the experience of being a father and a husband affected how you think of emotions and morality, and if so how?

I am in the thick of it, with two teenage daughters. What I think about it today is this: My children are not entitled to equal Kantian moral respect—they are not autonomous self-governing agents even to the extent that most adults are (whatever extent that is). But they are already fully equipped to make me feel guilty for saying that, thinking it, or acting upon it. They can debate about what they ought to be allowed to do with the best of us.

Another thing about parenthood: I lost the ability to appreciate certain kinds of dark fiction and sick humor involving bad things happening to innocent children. Some would say this is an improvement in my sensibilities due to greater maturity, but I disagree. I think my new patterns of response are good to have under the circumstances, but involve a kind of blindness to certain sorts of aesthetic and comic value. (My wife wandered by as I wrote that, and says I am a lunatic.)

What is your view on the increasing competitiveness faced by philosophers when they try to be admitted to a PhD program, get a tenure-track job, and get tenure? Do you think more competitiveness has led to better philosophy being produced on average? Do you think some changes are required in the way academic philosophy is organized at various career levels?

Good questions. I don’t know. I am hugely impressed by the high quality of so many of the young PhDs in philosophy these days. They are really great. They seem to emerge from graduate school with a much better sense of how to write a paper that constitutes a contribution to a debate, and how to construct an engaging talk, than most of us did when I got my degree.

I do worry a little that pressure to publish more at earlier stages leads to too much philosophy being published and to ever more specialized debates. But I am not one of the pessimists who think that we are no longer a profession that can recognize or welcome new voices or insights. Philosophy seems to me vibrant and increasingly open to different kinds of projects. It is in some trouble in the United States due to various cultural and economic forces at work here, so I am not at all convinced it affords good professional opportunities to many people going forward. But that is a different issue.

You were one of the three keynote speakers at the recent ISRE 2015 conference in Geneva, jointly with Tania Singer and Jennifer Lerner. What sense did you get of where emotion theory is heading from attending talks at the conference?

One main impression is of the breadth of work being done and the diversity of topics. Neuroscience of affect is clearly expanding, as it should be. There continues to be a great deal of work on emotion expression. And there were lots of talks on emotion and language, on regulation, and on appraisals. I really enjoyed Jennifer Lerner’s talk, but did not get to see much else on emotion and decision research. That’s a really lively area, and I have long been a big fan of her work.

There also seemed to be a lot of people working on emotion in relation to identities in various different senses, from very different directions and disciplines. There is talk of emotions in relation to a sense of self, a sense of personal responsibility, as well as various “social identities” and forms of “identification” with others. My sense at the moment is that while there is a lot of interesting work being done there, much of it is in distinct intellectual silos. If someone works out how to map the conceptual interconnections of those research projects, I think emotion and identity might prove to be an interesting interdisciplinary subfield. But perhaps that has already been done well and I am just behind the curve here.

Once I looked at the whole program it was clear that my aspiration of trying to drop in all over the place to get a sense of the field as a field was not really realistic. I tried to stretch myself a little, and go to some talks outside the areas I know best. But the poster sessions were an easier way to get a sense of the variety of things going on in a quick way. I thought a lot of those posters were terrific, and it looks like the future is bright. Most of the talks I attended were by philosophers, and there was a lot of very interesting material on emotion and perception, emotion and knowledge, and emotion and value.

What are your hobbies?

I like cooking and finding good food made by others, and I like trying to match wine to food. I cook a lot of different sorts of things, but Italian food is my home base and the area where I feel most comfortable throwing things together without a recipe. I also like to play squash, which I thought was better for my health than those other hobbies. I started playing in tournaments in my forties and have enjoyed that a lot, but injuries have slowed me down recently. Reading fiction is still a hobby, when there is time.

I also enjoy traveling very much, especially with my family. I’ve tried to include them in some of my professional travel. Family highlights include trips to Italy, Australia, Korea and Cambodia. My oldest daughter has been studying Chinese for a few years now, and we are going to take a trip to China in 2016.

You have lived in Columbus, Ohio since 1995, and you now hold the position of Professor of Philosophy and Department Chair at Ohio State University. What do you like and what do you dislike about living in Columbus? What are a handful of your favorite restaurants in town? Do you enjoy cooking, and if so do you have a favorite recipe to share?

Columbus has lots of important but unglamorous virtues. It’s easy to get around, people are friendly, and it is big enough that there are interesting new social groups to discover and new restaurants opening up all the time. It is one of those cities that allowed its center to be gutted and freeways to occupy its riverfront, but it has undergone a huge redevelopment and it is a lot more attractive now than when I moved here in 1995. Living in the middle of the city I can bike to work easily and walk to lots of restaurants, bars and coffee shops. The local and artisanal food scene has been growing like mad, and new craft breweries open all the time. I do wish we had more direct flights to the west, though. And while we have a lot of good Asian, African and South American places, we need more good Italian food.

For a visitor to town, I recommend the Northstar as a high quality casual place, or its sister Third and Hollywood for something a little nicer. Locals should check out La Tavola, the closest thing I know here to authentic Italian cooking.

My recipe is for a meat sauce for pasta—sorry, Andrea, I know this means you won’t be trying it. This sauce makes for a delicious meat lasagna, in combination with béchamel sauce and Parmigiano Reggiano. That’s my family’s favorite dish that I make. And it is also nice just served with pasta and the cheese. I make it in large batches so as to do both, and because it is a bit of a pain to make. It freezes well for three to six months if you don’t use it all, or the quantities below can be reduced. Here is the recipe:

Ingredients:

1 pound each of ground pork, beef and veal

1 cup each of finely diced onion, carrot and celery

2/3 lb of chicken livers (the secret ingredient)

a large handful of dried porcini mushrooms, reconstituted with boiling water

½ bottle white wine

2 cups chicken stock

1-2 cups whole milk

a 6 oz can tomato paste

salt & pepper

nutmeg

Procedure:

Brown the meat in separate batches in the heavy bottom pot, removing when browned to separate bowl. Soften the onions in butter or olive oil (both is best) on medium low heat. When they are beginning to soften add the carrots and celery, cook another five minutes until all are starting to soften. Add all the browned meat and turn up the heat. Brown this all together, stirring occasionally. When it starts sticking to the bottom of the pan, add half the wine and deglaze. Repeat that process with the other half the wine and then with the stock, half the stock at a time. This usually takes about half an hour.

Meanwhile, sauté the chicken livers in a separate pan. When the chicken livers are firm, remove from the pan and dice them up. Dice up the reconstituted porcini.

Once all the stock has been added and the pan deglazed several times, turn down the heat, add the milk, the chicken livers, the porcini, and cook at medium low for five minutes. Stir in the tomato paste. Add salt, pepper, and a little nutmeg. Turn down to low, partially cover, and allow to simmer for about an hour, stirring occasionally.

One mustn’t make this very often, but we like it when we do.

What are you working on these days?

I’m trying to finish up that Rational Sentimentalism book with Jacobson, while wrangling with my University to get more support for our department’s research and graduate programs. We are working on a chapter on emotions right now, which will defend a theory of certain natural emotions as a special kind of motivational state. This is very close in spirit to your motivational account, Andrea, though we disagree on some of the details. Our thinking was influenced by our conversations with you, and by the wonderful work of Nico Frijda that you first introduced us to many years ago now.

Please list five articles or books that have had a deep influence on your thinking

The Emotions, Nico Frijda

Wise Choices, Apt Feelings, Allan Gibbard

Reasons and Persons, Derek Parfit

“Freedom and Resentment” P.F. Strawson

Various essays by Bernard Williams, including “Moral Luck”

What do you think are the most pressing questions that future philosophy of emotions should be focusing on?

I’d like to see more work on the motivational role of emotions. I agree with your diagnosis that the main rivals in philosophy have been some kind of cognitivism and a feeling theory, and that neither explains some of the central emotional phenomena, which are motivational.

I also think philosophy of emotions needs to be better integrated with more areas of philosophy. Connections tend to run more toward moral philosophy, and we need to be learning more from other areas, especially philosophy of mind and perception, and epistemology. That is starting to happen, but in some ways I think that philosophy of emotion has been a bit insulated from the most sophisticated developments in those other areas. It will make more progress as we bring over more tools from other parts of the field. At the same time, we need to continue to look outside philosophy to the affective sciences. It is hard to keep abreast of all of this at once, but I think those who come closest to doing so will be writing the work that I most want to be reading in philosophy of emotion over the next decade.

References

D’Arms, J. (1995). “Evolution and the Moral Sentiments.” Ph.D. Thesis, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI.

D’Arms, J. (1996). “Sex, Fairness, and the Theory of Games.” The Journal of Philosophy 93(12): 615- 627

D’Arms, J. (2000). “When Evolutionary Game Theory Explains Morality, What Does it Explain?” The Journal of Consciousness Studies 7(1-2): 296-300.

D’Arms, J. (2000). “Empathy and Evaluative Enquiry.” Chicago-Kent Law Review: Symposium on Law, Psychology and the Emotions 74(4): 1467-1500.

D’Arms, J. (2009). “Envy.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Edward N. Zalta (ed.).

D’Arms, J. (2013). “Value and the Regulation of the Sentiments.” Philosophical Studies 163(1): 3-13.

D’Arms, J. & Jacobson, D. (1994). “Expressivism, Morality, and the Emotions.” Ethics 104: 739- 763.

D’Arms, J. & Jacobson, D. (2000). “The Moralistic Fallacy: On the ‘Appropriateness’ of Emotions.” Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 61(1): 65-90.

D’Arms, J. & Jacobson, D. (2009). “Regret and Irrational Action.” In D. Sobel and S. Wall (eds.), Reasons for Action, pp. 179-199. New York: Cambridge University Press.

D’Arms, J, & Jacobson, D. (2014) “Featured Philosophers: D’Arms and Jacobson.” Pea Soup: A blog dedicated to philosophy, ethics, and academia.

D’Arms, J. & Jacobson, D. (forthcoming). Rational Sentimentalism. New York: Oxford University Press.

Frijda, N.H. (1986). The Emotions. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Gibbard, A. (1990). Wise Choices, Apt Feelings. New York: Oxford University Press.

Gross, J. (2002). “Emotion regulation: Affective, Cognitive, and Social Consequences.” Psychophysiology 39: 281-291. Cambridge University Press.

Haidt, J. & Bjorklund, F. (2007). “Social intuitionists answer six questions about morality.” In W. Sinnott-Armstrong (ed.), Moral Psychology, Vol. 2: The Cognitive Science of Morality, pp. 181-217. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Parfit, D. (1984). Reasons and Persons. New York: Oxford University Press.

Skyrms, B. (2014). Evolution of the Social Contract. Irvine: Cambridge University Press.

Strawson, P.F. (1962). “Freedom and resentment.” Proceedings of the British Academy 48: 1-25.

Williams, B. (1981). Moral Luck. New York: Cambridge University Press.