An interview with Cain Todd

Michael Brady is Professor of Philosophy and Head of School at the University of Glasgow, which he joined in 2005. He was Director of the British Philosophical Association from 2011 until 2014, and Secretary of the Scots Philosophical Association from 2009 until 2012. He is on the Board of The Philosophical Quarterly, and subject editor responsible for Moral Philosophy, Political Philosophy, Aesthetics, and Philosophy of Religion for Oxford Bibliographies Online. His work on the philosophy of emotion is at the forefront of current discussions and his book Emotional Insight (2013) offered an influential critique of perceptual theories of emotion, while also providing a positive account of the valuable epistemic role that emotions can play in our lives. More recently, he co-led a major three-year interdisciplinary project on The Value of Suffering, one result of which was the monograph Suffering & Virtue, published in 2018, in which he argues that suffering is vital for the development of virtue, and hence for us to live happy or flourishing lives.

Where did you grow up?

I grew up in Stockport, which is a large industrial town a few miles south of Manchester city centre. Friedrich Engels wrote in 1844 that it was ‘renowned as one of the duskiest, smokiest holes’ in the whole of the industrial area. It’s a bit better these days, but pales a bit in comparison with Manchester itself. It has a very nice viaduct.

Did those early years have any noticeable influence on your choice to be an academic philosopher? When and why did you decide to pursue philosophy?

I can mention three things that had an influence on my choice to becoming an academic philosopher. One was my secondary school, Xaverian College, which is in Rusholme, Manchester. As you might imagine at a Catholic grammar school run by the Xaverian brothers, religious education was prominent. But it was a remarkably liberal school, for 1970s Manchester, and much of our religious education focused on moral, ethical, and political issues, and discussion of these. So I had a broad introduction to philosophy of religion and ethics – and the importance of discussing and arguing about these – throughout my years at Xaverian.

The second was my father’s decision to take an Open University degree. My father left school at 14 and worked as a textile artist at the Calico Printers’ Association, and then as an art teacher, but decided to do a Humanities degree in his 40s. I remember looking through his philosophy course texts as a teenager – The Republic, The Meditations – and really enjoying them, which doubtless sowed another seed.

The third factor was that I was a particularly recalcitrant first year student of Geology and Geography at Liverpool University, and decided that I didn’t want to spend my university years sketching trilobites in a lab or camping in a freezing field. So I had an interview with Professor Stephen Clark, who was Head of Philosophy at the time, and he agreed to let me join, conditional on a correct answer to a logic puzzle and a promise to work hard. I’ve tried to keep that promise ever since.

You did your PhD at the University of California at Santa Barbara, after having studied for a Master’s in Philosophy at King’s College, University of London, and a BA with Honors in Philosophy at the University of Liverpool. What was it like studying in the US after having been in Britain?

Moving to Santa Barbara was somewhat of a random decision. I definitely wanted to live and study in the US, having lived in London for three years, and worked in publishing as a desk editor, production manager, and layout artist after my Master’s at Kings. I wanted to move, in part, because I had a deep fascination of and love for American culture – initially films, but from the early 80s American music became something of an obsession. But I was also desperate to leave the UK after 13 years of a Conservative government, 11 of these with Margaret Thatcher as Prime Minister. I was pretty depressed after the 1992 General Election, when John Major triumphed despite polling suggesting a Labour victory, and that really forced my hand.

Why did you choose Santa Barbara? What was your PhD thesis on?

Why UCSB? (i) they had accepted me, (ii) there was generous financial assistance on offer, and (iii) it was in California and had a very good reputation. I had a fantastic six years there. It was a supportive faculty with some outstanding philosophers, a really great group of grad students, and the city is beautiful. It struck me as considerably less pressured than the UK – although highly competitive nonetheless. I think that this is because US academics can spend more time on teaching and research, and less time on administration, and have more freedom in what and how they teach than their UK counterparts. They seem considerably happier as a result. My thesis was on internalism and externalism in meta-ethics and epistemology. As this suggests, it wasn’t the most focused work. But I learned a lot doing it, it was a fine place indeed to do one’s graduate studies.

You started working in the Department at Glasgow in 2005, having previously taught at the University of Stirling. How did you find the start of your academic career? What were you working on at the time?

It was something of a shift to move from sunny California to the rain-swept central belt of Scotland, and from a place where an English accent generates friendly curiosity and a warm reception to a location where it can have a somewhat different effect. But I was very lucky to start my academic career at the University of Stirling, where the Philosophy Department was a model for what an academically excellent and collegial department should be. At Stirling my interests shifted to normative ethics, and in particular to thinking about the virtues, and rather away from meta-ethics. The move to Glasgow was a difficult one to make, given how much I loved working in Stirling. But I was already living in Glasgow with my partner, and the opportunity to join the department there – where Francis Hutcheson, Thomas Reid, and Adam Smith all worked – was too good to resist. I’ve not regretted the move at all. Glasgow is a remarkable city and a wonderful place to live and work. So I’m extremely luck to have ended up here.

Was there anyone in Stirling you saw as an inspiration or mentor?

Professor Antony Duff was a particularly supportive mentor, and showed it was possible to combine dedication to philosophical research with concern for colleagues and administrative skill. I’ve not really met anyone else who manages to carry this off; Antony remains an inspiration to me, and to many others I’m sure.

When did you first turn your attention to emotion? What was it that drew you to it? What was the focus of your early work on emotion and how was your work received?

I guess my work in virtue directed the move to focus on emotion. I was impressed and very much influenced by Linda Zagzebski’s seminal work Virtues of the Mind, a book which myself and my good friend Duncan Pritchard worked through over many sessions in Stirling pubs in 2002-3. Zagzebski makes emotion prominent in her account of what a virtue is, and taking my cue from her, I thought I should do some work trying to figure out what emotion is. So I guess 18 years later, I’m still working on this, though I think I’ve made some progress. The focus of my early work was on the relation between emotion and reason – inspired this time by work on the nature of emotion by the late and great Peter Goldie. I had a year’s research leave, spent in Australia in 2005, working on this topic. As with most of the things I write, the reception was mixed, with a strong leaning towards the negative. But as with most things I publish, numerous revisions and amendments knocked the papers into shape, and a more coherent research project, centred on the epistemic value of emotional experience, started to emerge.

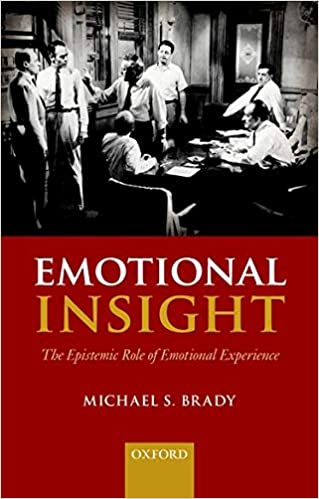

Your book Emotional Insight (2013) offered perhaps the most comprehensive critique of perceptual theories of emotion and some significant challenges to the commonplace idea that emotions can give us information about the world. But you also present a positive conception of the epistemic value of emotions. What do you think were the most important or influential ideas in the book? Is there anything you’d change?

I’m pleased and quite proud of Emotional Insight. I developed pretty late as a philosopher, and it was probably the first thing I’d ever written that I felt genuinely happy about. It reflected my thinking about emotion at the time, and for this reason alone I wouldn’t change anything about it. But there are things I got wrong, both in terms of content and tone, and I think that a number of claims I made were too strong – as quite a few critical articles have pointed out in the intervening years. The most important idea remains the central theme of the book – which is that the perceptual model both overstates, and underplays, the epistemic value of emotion. It overstates it by saying that the epistemic yield of emotion is really like that of perception. It underestimates emotions’ importance by neglecting the extent to which emotions themselves move us to search for reasons, assess and reassess the evaluative situation. In this way they play a very important role – one that has been neglected, by too much focus on the perceptual model – in allowing us to understand the evaluative world.

What’s your sense of the current standing of perceptual theories amongst philosophers, and of the philosophy of emotion in general? Have there been any new developments or models that you find particularly interesting or important?

I think that the perceptual model still enjoys a high standing amongst philosophers – in part because it is still a relatively new option to explore, and in part because it has very smart and sophisticated thinkers defending the view and developing enhanced versions. Christine Tappolet’s 2016 book Emotions, Values, and Agency is perhaps the best known recent defence and expansion of the model, and impressive work it is. Michael Milona and Robert Cowan have also made important defences of the model, and pushed it in interesting new directions, and considered more broadly the nature of normative and evaluative perception.

What do you think of the current relationship between philosophical accounts of emotion and empirical research into emotion?

I don’t think I’m reading enough at present to have a grasp on this! I would hope that any further work I do on the perceptual model, and indeed in other areas of philosophy, is informed by empirical thinking on the issues. There are obviously limits – mainly in terms of time, but also in expertise – as to how much empirical research one can survey. This is where forging collaborative links with people in the relevant empirical disciplines can help a great deal: it’s relatively easy to ask, although risks trying the patience if you ask too often, ‘what are the 10 things I have to read in the recent empirical literature on topic X?’ At least then you can be sure not to have overlooked too many of the important empirical contributions to the debate.

The other important theme in your recent research concerns the nature of pain and suffering. You recently co-led a major three-year interdisciplinary project on the topic the Value of Suffering, funded by the Templeton Foundation. What was it like leading this project?

The project was a fantastic experience, not least because I got to work closely with my colleagues David Bain (co-PI) and Jennifer Corns (postdoc, now permanent lecturer at Glasgow) for three years and put on 14 workshops, 3 major international conferences, and publish a whole bunch of articles, co-edited books, and two monographs. We also managed to organise conferences in Paris and Sydney and Toronto with collaborators there, which was obviously a big plus. Despite all of the effort putting the application together, and significant amount of work over the three-year period, a large project like this is worth every bit of effort.

What was your experience of the value and effectiveness of its interdisciplinary aspects? Has your own work on emotion, or suffering, been influenced by empirical work?

We managed to collaborate with incredible people – those who we invited to Glasgow, those who invited us to other places – and learn a great deal. The interdisciplinary element was, as you might imagine, mixed – although that depended to a great extent on who was speaking at the events. Some psychologists, clinicians, and neuroscientists were incredibly engaging, and brought their expertise directly to bear on things that interested the philosophers. Some of the philosophers were pretty terrible at engaging, and convincing others of the need for and importance of their own philosophical work, to those in other disciplines. This is hardly surprising, since within disciplines we of course find a massive variation in how well people communicate, engage, enthuse, and educate. I learnt a lot from the psychologists, and in particular the work of Brock Bastian and Siri Leknes. Brock and Siri do fascinating experimental work on the nature and value of pain, in a way that centres and highlights the philosophical themes and ideas that we were all interested in. I also learnt a lot from engaging with a very many philosophers with considerable empirical knowledge and expertise; Jen Corns was prominent amongst these. And Fiona Macpherson is a model of someone who does outstanding philosophical work that is fully integrated with and informed by empirical research. So, if readers are wondering how this can be done well, they should look to Fiona’s work and learn from it.

Your recent book, Suffering and Virtue (2018), argues that suffering is vital for the development of virtue, and hence for us to live happy or flourishing lives. Can you say a little here about the distinctive account of suffering you develop in the book? How does it make sense of emotional suffering?

One of the difficult lessons I learnt when starting research on the nature of pain was that pain is such a complex, complicated thing. It is a state or process that provides the person with information; has an obvious affective quality; and has considerable motivational force. I think that these features can be best captured on a desire-view, albeit one that is itself quite complicated.

On my account, pain is a particular kind of sensation that we desire cease. Painfulness involves a higher-order desire: that the experience of pain (the sensation that we desire cease) is something that we desire cease. Unpleasantness is a broader category, including many different kinds of sensation than pain sensations. Finally, suffering involves a further higher-order desire: an occurrent desire that an unpleasant experience cease. This is complex indeed. But such a structure is needed, I think, to capture the fact that there can be dissociation between pains and motivation; that we can suffer even though experiencing relatively low intensity pain; and that suffering can involve and be responsive to our attitudes and thoughts, since these can generate the occurrent desire that some unpleasantness cease.

I also think that a desire account is broad enough to capture the obvious fact that creatures unable to entertain high-level thoughts about badness – such as young children and non-human animals – can suffer. Many accounts of suffering strike me as over-intellectualised. An advantage of my account is that it appeals only to states of sensation and desire that children and non-human animals can also have. The account can also be expanded to make sense of emotional suffering, since certain emotional states – such as grief, loneliness, disappointment – are unpleasant, and when they are unpleasant enough we typically form an occurrent desire that they cease.

So physical and emotional suffering have the same structure: in each, an occurrent desire is directed towards an unpleasant affective state, although the kinds of state might be different. (Painful experiences are different from states of grief or disappointment.) Given the dearth of philosophical accounts of suffering, mine seems distinctive insofar as it is the first to work out a desire account in any level of detail.

A common theme throughout your works is an interest in virtue and the epistemology of virtue. What is it that attracts you to this topic? Do you think that philosophy can illuminate what it is to be a good person, or what our well-being consists in?

As before, my interest in virtue goes back a long way, as does my interest in the epistemology of virtue – to when I was at Stirling, and a colleague of Duncan’s. I guess initially it was a topic that combined our interests, and we could talk about in the pub. Around that time I because increasingly interested in the epistemic value of emotion – and here Chris Hookway’s work struck me as rich and fascinating. Chris contributed a paper to a conference me and Duncan organised, on moral and epistemic virtue, which later became an edited book. The topic of the epistemic importance of emotion, and the connection of emotion with epistemic virtue, seemed ripe for detailed examination. It’s one of those topics that strikes me as immediately philosophically interesting, tying as it does a common-sense idea – that emotions tell us things – and a lack of understanding about how emotions tell us things. I don’t think I’ve got a complete answer to the latter, of course, but I think that my work is a tentative first step in that direction. Since I think that philosophy can make (slow) progress telling us what it is to be a good thinker, inquirer, and knower, I think it can make progress in telling us what it is to be a good person. In one sense, this is a conceptual question: I am very taken with Martha Nussbaum’s idea of the virtues being those traits of character that enable us to cope well with important aspects of our lives. It is difficult to see how being a good person couldn’t be closely connected with coping well.

In another sense, philosophy can illustrate important truths about elements of well-being: for instance, that pain isn’t simply a sensation; that it can be responsive to higher-order states involving desires and thoughts; that emotions have an important bodily component, and that changing one’s bodily states and can have important effects on how one feels; and so on. This isn’t even touching philosophical accounts of what it is to be a morally good person. So I’m an optimist when it comes to philosophical contributions to the good life. Admittedly, the take-up of philosophical ideas is less-than-perfect, in part because philosophical writing and thinking is difficult, complex, and messy – and people want answers to questions about being happy that are easy to digest and to follow. It’s not surprising there’s a mismatch here. (This is a general point, and it’s why analytic philosophers rarely appear on tv or on the radio, where quick and pithy solutions to moral and political problems are requested, and philosophers are unable to provide them, at least in under 30 minutes.)

Do you see all of your research interests – on emotion, suffering, virtue – as forming a kind of unity? Do you have an overarching philosophical view you are striving towards?

I don’t have an overarching philosophical view. I’m a bit suspicious of them – at least, of the ones that people adopt really early and then spend the rest of their philosophical careers defending. This is probably because I’m rather late to the party in developing philosophical ideas. But it also reflects what I said earlier: that philosophical problems and questions are very difficult, involving very many moving parts and theoretical options, and that progress (at least, my progress) is painfully slow. I guess my research interests have been coming together for a while, but that’s only because I thought that I need to understand what emotions are if I am to understand virtue; and then I realised the importance of virtue for emotional regulation; and then I realised the importance of negative emotion in the cultivation of virtue; and so on. But it certainly wasn’t a plan for all of these ideas to come together. I guess if you work on a topic and related questions long enough, patterns and unifying themes start to emerge. This is often the way, as it happens, that good PhD theses emerge: after two or three years of struggling with issues, grad students suddenly see a pathway and an organising idea. Of course, other grad students start off with a complete picture of what they want to do, and then spend a few years filling that in. But as I said, I was never smart enough, or confident enough, to have that kind of clear vision.

What is your next big project or research goal?

Currently I’m Head of the School of Humanities at Glasgow, a role which I love, but which involves very significant amounts of administrative and managerial work. So this will hamper any big projects in the next few years. But I try to eke out a bit of time each day – sometimes only 15 minutes – to think about and work on research. This is something that I strongly recommend. (Alex Miller gave me the very sound advice to do some research each day, even if it’s reading one page of an article, and it has proved one of the two best pieces of academic advice I’ve ever had. The other is: there is always too much to do, so don’t worry about not doing everything.)

One concrete thing I’m working on is a collaboration with a team of brilliant psychologists in the US, on a Templeton-funded project led by Eranda Jayawickreme at Wake Forest. The project focuses on the value of exemplars for promoting post-traumatic growth and well-being after adversity. I’m currently writing something on exemplars for this, and acting as philosophical consultant for their major psychological study, working with the Wake Forest team and Seattle-based clinical psychologist Ann Marie Roepke. As a result of working on this, I plan to write a longer piece on philosophical accounts of trauma. I get a year’s research leave after my stint as Head of School is over, and so that longer piece might turn into a book, if it goes well.

What are five articles or books that have influenced you?

- Republic (Plato)

- Meditations (Rene Descartes)

- A Treatise of Human Nature (David Hume)

- Virtues of the Mind (Linda Zagzebski)

- The Emotions (Peter Goldie)

Outside of academic philosophy, you are Philosopher-in-Residence at the Manchester-based theatre and performance company Quarantine, and have worked with them on a number of productions. Can you say more about that, how you became involved and what your role is? Does an interest in drama connect with your central research interests?

Quarantine’s Artistic Director, Richard Gregory, is one of my oldest friends. For a long time – before Quarantine existed – we would walk about philosophical issues in theatre and performance, partly because I was really interested in the work that Richard does, partly because he has the kind of curious and inquiring mind that lends itself well to philosophical discussions. So working with Quarantine arose naturally from my friendship with Richard.

I’ve been closely involved with three main productions – Make-Believe from 2009, Entitled from 2011, and Summer.Autumn.Winter.Spring from 2014-16. Quarantine’s productions are not really ‘about’ things in the way a theatrical piece traditionally is; but they are interested in and involve explorations of concepts, ideas, and relations. Make-Believe investigated issues of truth, authenticity, identity; Entitled looked at hope, privilege, and disappointment; the quartet was a massive piece about living, dying, and our relationship with time.

I find working with Quarantine fascinating and stimulating – because my role is to talk to the producers, performers, technicians about these concepts and ideas, about how they are understood in philosophy, and to discuss what these things mean to all involved. It’s not that these discussions end up scripted, or form an obvious part of the shows. It’s more that they are attempts to come to some kind of understanding of the concepts, and then see how this understanding might inform what goes on in the production and performance. So it is a philosophical element in the intense period of research and development that goes into each show. I think – as do others – that Quarantine produce amazing work. You can read about them here: https://qtine.com/home/. An illustrated volume about the quartet, with essays about its various themes, was published by Manchester University Press in 2019. (Details here.) I was one of the editors. I’m very proud of this one as well.

You are a football fan, and you have written on suffering in sport. Do you see your research as having any bearing on your own personal attitudes to, for example, your own well-being and emotional life? Or are your philosophical views perhaps shaped by these?

I know that people are sceptical about the extent to which philosophical views affect the lives of those who hold them: witness Eric Schwitzgebel’s fascinating work on the moral behaviour of ethicists. At the same time, it would be strange if ideas and topics that occupy much of one’s working life don’t have some effect on one’s personal attitudes, well-being, and emotional life. I guess my work on the value of suffering makes me somewhat more inclined to be positive in the face of adversity, and to consider the possibility that something good might come out of bad times. This isn’t to engage in ‘brightsiding’ – or at least I hope that it isn’t – because taking an optimistic attitude is perfectly possible with hating the fact that times are bad, and wishing that one’s pain and suffering would cease and things get better. Being more optimistic doesn’t mean being dishonest, therefore. When it comes to sport, this is clearly a good attitude to have, or at least a good attitude if one is to develop the virtues of loyalty and solidarity with one’s team and your fellow supporters. It’s also good to bear in mind that the good times will be so much better as a result of suffering through the bad times! Given that misery is the lot of most sports fans, most of the time, philosophical thinking about the value of suffering might well be a panacea. It certainly is for me.