Gerben A. Van Kleef, Department of Psychology, University of Amsterdam

Gerben A. Van Kleef, Department of Psychology, University of Amsterdam

My colleagues and I are interested in the social consequences of emotions. In our research, we adopt a social-functional approach to emotion, assuming that emotions play a vital role in regulating social interaction (Fischer & Manstead, 2008; Frijda & Mesquita, 1994; Keltner & Haidt, 1999; Parkinson, 1996). Moving beyond the traditional questions of how our emotions arise and how they influence our own thinking and behavior, we explore how one person’s emotional expressions influence the feelings, thoughts, and actions of others.

Such interpersonal effects of emotions, whether deliberate or inadvertent, are omnipresent in close relationships, in the workplace, in politics, in advertisement, and in most other forms of human interaction. A homeless person may express sadness in the hopes of extracting change from shoppers. A colleague may smile when asking for a favor. A manager may express anger to force workers to be punctual. A father may express pride to reinforce the desired behavior of his daughter. By examining the social consequences of such emotional expressions in a diverse array of settings, we strive to uncover the basic principles that govern the social effects of emotions. Ultimately, we hope to shed new light on the fundamental question of why we have emotions in the first place.

Emotions As Social Information (EASI) Theory

My colleagues and I have developed what we call the Emotions As Social Information (EASI) theory (Van Kleef, 2009, 2010; Van Kleef, De Dreu, & Manstead, 2010; Van Kleef, Homan, & Cheshin, 2012; Van Kleef, Van Doorn, Heerdink, & Koning, 2011) to explain and predict the social effects of emotions and to guide research in this area (these and other relevant papers mentioned in this article can be retrieved from the publications page of my website at http://home.staff.uva.nl/g.a.vankleef). A fundamental assumption of the theory is that social life is ambiguous, and that people therefore turn to others’ emotions to inform their understanding of the situation and the people involved in it, and to determine their course of action (also see Manstead & Fischer, 2001).

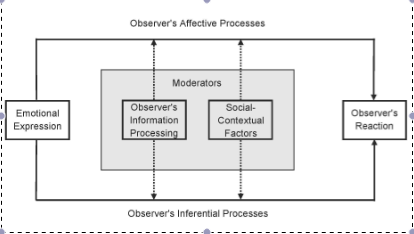

EASI proposes that emotional expressions shape behavior and regulate social life by eliciting affective reactions in observers (i.e., reciprocal and complementary emotions and sentiments about the expresser) and by triggering inferential processes in observers (i.e., inferences about the source, meaning, and implications of the expresser’s emotion). These affective reactions and/or inferential processes in turn inform observers’ behavior. Imagine you are meeting a colleague in a bar, and you show up 30 minutes late. Your colleague expresses anger regarding your tardiness. On the one hand, your colleague’s anger may lead you to several inferences: you realize that you are late, that your lateness is inappropriate, and that s/he is upset with you about your being late. This sequence of inferences may motivate you to be punctual next time (behavior). On the other hand, the anger directed at you may upset you and make you dislike your colleague (affective reactions), and possibly cause you to decide not to meet anymore at all (behavior).

In some cases the two processes fuel similar behavioral responses, as when the distress of a loved one simultaneously leads us to feel mutual distress and compassion (affective reactions) and to realize that something is wrong (inference), both of which motivate supportive behavior. In other cases, affective reactions and inferential processes drive opposite behaviors (as in the example of the colleague). In such instances behavioral responses to others’ emotional expressions depend on the relative strength of the two processes (Van Kleef, 2009).

The relative strength of inferential and affective processes depends on two main classes of variables. First, a basic commitment of EASI is that, since emotional expressions are a source of information, their social effects are modulated by the observer’s information processing motivation and ability. Information processing ability depends on individual characteristics such as intelligence and on situational influences such as distraction or cognitive load. Processing motivation depends on dispositional factors such as the need for cognitive closure (i.e., the desire to reach quick decisions without considering all available information) and on situational factors such as time pressure (De Dreu & Carnevale, 2003). The more thorough the information processing, the stronger the predictive power of inferences; the shallower the information processing, the stronger the predictive power of affective reactions (Van Kleef, 2009).

Schematic representation of Emotion as Social Information (EASI) theory. EASI posits that the social effects of emotions (i.e., the effects of one person’s emotional expressions on another person’s behavior) are mediated by affective and inferential processes. Inferential processes become relatively more predictive of an observer’s behavioral reaction to the degree that the observer engages in more thorough information processing and perceives the emotional expression as appropriate, while affective processes become more predictive when information processing is low and the emotional expression is deemed inappropriate.

Second, the relative strength of affective versus inferential processes depends on social-contextual factors that shape the perceived appropriateness of the emotional display (Shields, 2005). Perceived appropriateness depends on characteristics of the emotional expression (e.g., intensity, authenticity), the situation (e.g., emotional display rules), the expresser (e.g., gender, group membership), and the perceiver (e.g., desire for social harmony). Generally speaking, affective reactions become more predictive of behavior than inferential processes to the degree that emotional displays are deemed inappropriate (Van Kleef, 2009).

Returning to the earlier example, when confronted with your colleague’s anger you would be more likely to better your behavior to the degree that you are motivated and able to engage in thorough information processing and you feel that your colleague’s anger is appropriate. Figure 1 provides a (simplified) schematic summary of EASI theory.

Some Data on Emotions as Agents of Social Influence

To enhance understanding of the social nature of emotion, my colleagues and I have studied the interpersonal effects of discrete emotions such as anger, sadness, disappointment, guilt, regret, disgust, happiness, and pride in a variety of social and organizational settings. In particular, we have focused on social interactions involving persuasion, compliance, conformity, conflict, negotiation, leadership, team performance, personal relationships, and sports. Most of our research is experimental, employing a wide array of methods (e.g., behavioral observation, physiological data, eye-tracking, self-report and peer-report data, and objective performance outcomes). We complement this experimental work with field studies, using questionnaires, critical incidents methods, and longitudinal designs to gain rich data about the role of emotion in everyday social and organizational life. Below I provide some illustrative examples of research from our lab.

According to EASI, people may express emotions to change others’ behavior. But which emotions are successful at instigating desired behavioral changes, and

Team performance as a function of leader’s emotional display and followers’ level of agreeableness (source: Van Kleef et al., 2010, Psychological Science). Teams consisting of relatively low-agreeable followers performed better after their leader expressed anger rather than happiness regarding their performance. In contrast, teams consisting of relatively high-agreeable followers performed better after their leader expressed happiness rather than anger.

under which conditions? We demonstrated that expressing anger can help negotiators get a better deal, provided that the counterpart is sufficiently motivated to process the implications of the anger (Van Kleef, De Dreu, & Manstead, 2004) and perceives the anger as relatively appropriate (Van Kleef & Côté, 2007).

We also found that expressing disappointment can help to extract concessions, whereas expressing guilt invites exploitation (Van Kleef, De Dreu, & Manstead, 2006). In another line of research, we showed that leaders’ expressions of anger increase followers’ motivation and performance compared to expressions of happiness, but only when followers engage in thorough information processing (Van Kleef et al., 2009) and when they have a low concern for social harmony (e.g., because they score low on agreeableness; Van Kleef, Homan, Beersma, & Van Knippenberg, 2010; see Figure 2).

In another study, an instructor’s anger improved students’ learning performance compared to happiness, as reflected in better recognition and recall of word pairs (Van Doorn, Van Kleef, & Van der Pligt, in press). Finally, a series of studies on group decision-making revealed that expressions of anger of a majority can enforce conformity in a deviant minority, provided that the deviant is motivated to be accepted by the group and sees conformity as a means to achieve acceptance (Heerdink, Van Kleef, Homan, & Fischer, 2013).

In our research on the social effects of emotions we often consider the role of power, which is commonly defined in terms of asymmetrical control over valued resources (Keltner, Gruenfeld, & Anderson, 2003). Power tends to lower the motivation to attend carefully to the needs and desires of other people (Fiske & Dépret, 1996; Keltner, Van Kleef, Chen, & Kraus, 2008). As such, power may undermine the social functionality of emotional expressions by making observers less attentive to those expressions.

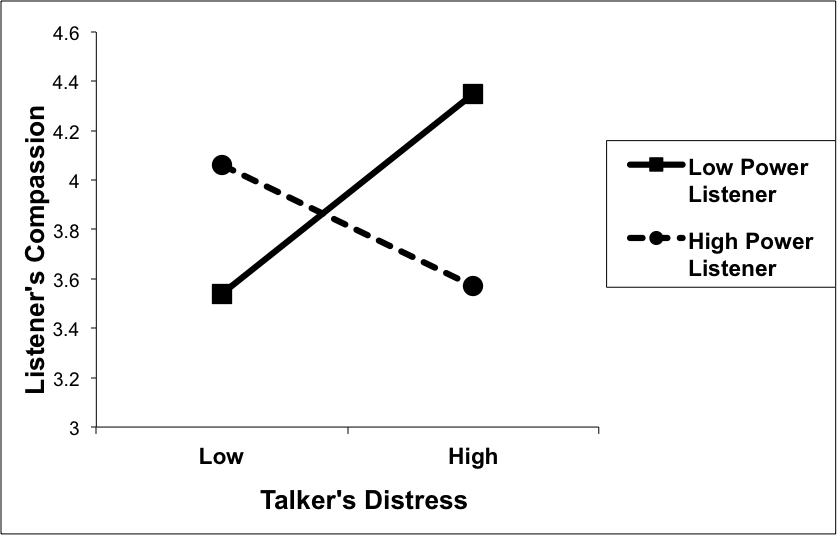

Listener’s compassion as a function of talker’s distress and listener’s power (source: Van Kleef et al., 2008, Psychological Science). Listeners with a low sense of power were highly responsive to the emotions of their conversation partner; the more distressed the partner was while talking, the more compassion they felt while listening. In contrast, listeners with a high sense of power were impervious to their conversation partner’s suffering.

Accordingly, in one of our studies conversation partners who experienced a greater sense of power exhibited dampened feelings of distress and compassion (see Figure 3), both physiologically and experientially, when listening to a talker’s stories of suffering, which in turn led the talker to feel poorly understood (Van Kleef et al., 2008).

We have also found that high power reduces behavioral responsiveness to anger expressions in negotiations (Van Kleef et al., 2004; Van Kleef, De Dreu, Pietroni, & Manstead, 2006). These studies show that power modulates the social effects of emotions.

The accumulating evidence from these and other studies supports the basic tenets of EASI theory. At the same time, new empirical insights prompt continuous updating of the theory. This process is far from over—in fact, we have only just begun. I am very much looking forward to further exploring the many intricacies of the social effects of emotions together with my fabulous team of collaborators and to unravel emotion’s social raîson d’être.

For more information, see: (a) http://home.staff.uva.nl/g.a.vankleef; (b) www.EASI-lab.nl

References

De Dreu, C. K. W., & Carnevale, P. J. D. (2003). Motivational bases of information processing and strategy in conflict and negotiation. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 35, 235-291.

Fischer, A. H., & Manstead, A. S. R. (2008). Social functions of emotion. In M. Lewis, J. Haviland, & L. Feldman Barrett (Eds.), Handbook of emotion (3rd edn.). New York: Guilford.

Fiske, S. T., & Dépret, E. (1996). Control, interdependence, and power: Understanding social cognition in its social context. European Review of Social Psychology, 7, 31-61.

Frijda, N. H., & Mesquita, B. (1994). The social roles and functions of emotions. In S. Kitayama, & H. S. Markus (Eds.), Emotion and culture: Empirical studies of mutual influence (pp. 51-87). Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association.

Heerdink, M. W., Van Kleef, G. A., Homan, A. C., & Fischer, A. H. (2013). On the social influence of emotions in groups: Interpersonal effects of anger and happiness on conformity versus deviance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 105, 262-284.

Keltner, D., Gruenfeld, D. H., & Anderson, C. (2003). Power, approach, and inhibition. Psychological Review, 110, 265-284.

Keltner, D., & Haidt, J. (1999). Social functions of emotions at four levels of analysis. Cognition and Emotion, 13, 505-521.

Keltner, D., Van Kleef, G. A., Chen, S., & Kraus, M. (2008). A reciprocal influence model of social power: Emerging principles and lines of inquiry. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 40, 151-192.

Manstead, A. S. R., & Fischer, A. H. (2001). Social appraisal: The social world as object of and influence on appraisal processes. In K. R. Scherer, A. Schorr, & T. Johnstone (Eds.), Appraisal processes in emotion: Theory, research, application (pp. 221-232). New York: Oxford University Press.

Parkinson, B. (1996). Emotions are social. British Journal of Psychology, 87, 663-683.

Shields, S. A. (2005). The politics of emotion in everyday life: “Appropriate” emotion and claims on identity. Review of General Psychology, 9, 3-15.

Van Doorn, E. A., Van Kleef, G. A., & Van der Pligt, J. (in press). How instructors’ emotional expressions shape students’ learning performance: The role of anger, happiness, and regulatory focus. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General.

Van Kleef, G. A. (2009). How emotions regulate social life: The emotions as social information (EASI) model. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 18, 184-188.

Van Kleef, G. A. (2010). The emerging view of emotion as social information. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 4/5, 331-343.

Van Kleef, G. A., & Côté, S. (2007). Expressing anger in conflict: When it helps and when it hurts. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 1557-1569.

Van Kleef, G. A., De Dreu, C. K. W., & Manstead, A. S. R. (2004). The interpersonal effects of emotions in negotiations: A motivated information processing approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87, 510-528.

Van Kleef, G. A., De Dreu, C. K. W., & Manstead, A. S. R. (2006). Supplication and appeasement in conflict and negotiation: The interpersonal effects of disappointment, worry, guilt, and regret. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91, 124-142.

Van Kleef, G. A., De Dreu, C. K. W., & Manstead, A. S. R. (2010). An interpersonal approach to emotion in social decision making: The emotions as social information model. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 42, 45-96.

Van Kleef, G. A., De Dreu, C. K. W., Pietroni, D., & Manstead, A. S. R. (2006). Power and emotion in negotiation: Power moderates the interpersonal effects of anger and happiness on concession making. European Journal of Social Psychology, 36, 557-581.

Van Kleef, G. A., Homan, A. C., Beersma, B., & van Knippenberg, D. (2010). On angry leaders and agreeable followers: How leader emotion and follower personality shape motivation and team performance. Psychological Science, 21, 1827-1834.

Van Kleef, G. A., Homan, A. C., Beersma, B., van Knippenberg, D., van Knippenberg, B., & Damen, F. (2009). Searing sentiment or cold calculation? The effects of leader emotional displays on team performance depend on follower epistemic motivation. Academy of Management Journal, 52, 562-580.

Van Kleef, G. A., Homan, A. C., & Cheshin, A. (2012). Emotional influence at work: Take it EASI. Organizational Psychology Review, 2, 311-339.

Van Kleef, G. A., Oveis, C., Van der Löwe, I., LuoKogan, A., Goetz, J., & Keltner, D. (2008). Power, distress, and compassion: Turning a blind eye to the suffering of others. Psychological Science, 19, 1315-1322.

Van Kleef, G. A., Van Doorn, E. A., Heerdink, M. W., & Koning, L. F. (2011). Emotion is for influence. European Review of Social Psychology, 22, 114-163.