Elaine Hatfield, Department of Psychology, University of Hawaii and Richard L. Rapson,

Elaine Hatfield, Department of Psychology, University of Hawaii and Richard L. Rapson,  Department of History, University of Hawaii

Department of History, University of Hawaii

January 2016 – It is hard to believe, but there was a time, perhaps 50 years ago, when many scholars would insist with a straight face that it was ridiculous to study cognition or emotion since neither was an observable phenomenon. Edward Thorndike, John B. Watson, and B. F. Skinner reigned. Behavioral science meant the study of behavior.

At the University of Minnesota, one Friday night, a colleague—and in his defense, he’d had a lot to drink—mocked Ellen Berscheid and me for our interest in emotion (villain’s name available on demand). We found ourselves in the absurd position of trying to convince him that humans really do possess thoughts and feelings. “Not so,” slurred our adversary. Finally, beaten down by Ellen’s compelling logic, he acknowledged that rats may possess cognition and emotion; but, still, humans did not. Today, only devotees of the Flat Earth Society could possibly take his side in such a wondrous argument. Cognition and Emotion are now considered so critically important to an understanding of humankind that they comprise fields of their own.

Even more, if the study of emotions were “taboo,” the study of passionate love simply lay beyond the pale. It wasn’t a respectable topic of study; it wasn’t amenable to scientific investigation, there was no hope of finding out anything about it in our lifetime. And it wasn’t “hot”—the hot topics in the 1960s were mathematical modeling, learning theory, and rats in runways. As women in a man’s scholarly world, however, Ellen Berscheid and I didn’t have to worry about acceptance—we couldn’t ruin our non-existent reputations. So we decided to study passionate love.

We defined passionate love this way:

A state of intense longing for union with another. Passionate love is a complex functional whole including appraisals or appreciations, subjective feelings, expressions, patterned physiological processes, action tendencies, and instrumental behaviors. Reciprocated love (union with the other) is associated with fulfillment and ecstasy; unrequited love (separation) with emptiness, anxiety, or despair (Hatfield & Sprecher, 1986, p. 383).

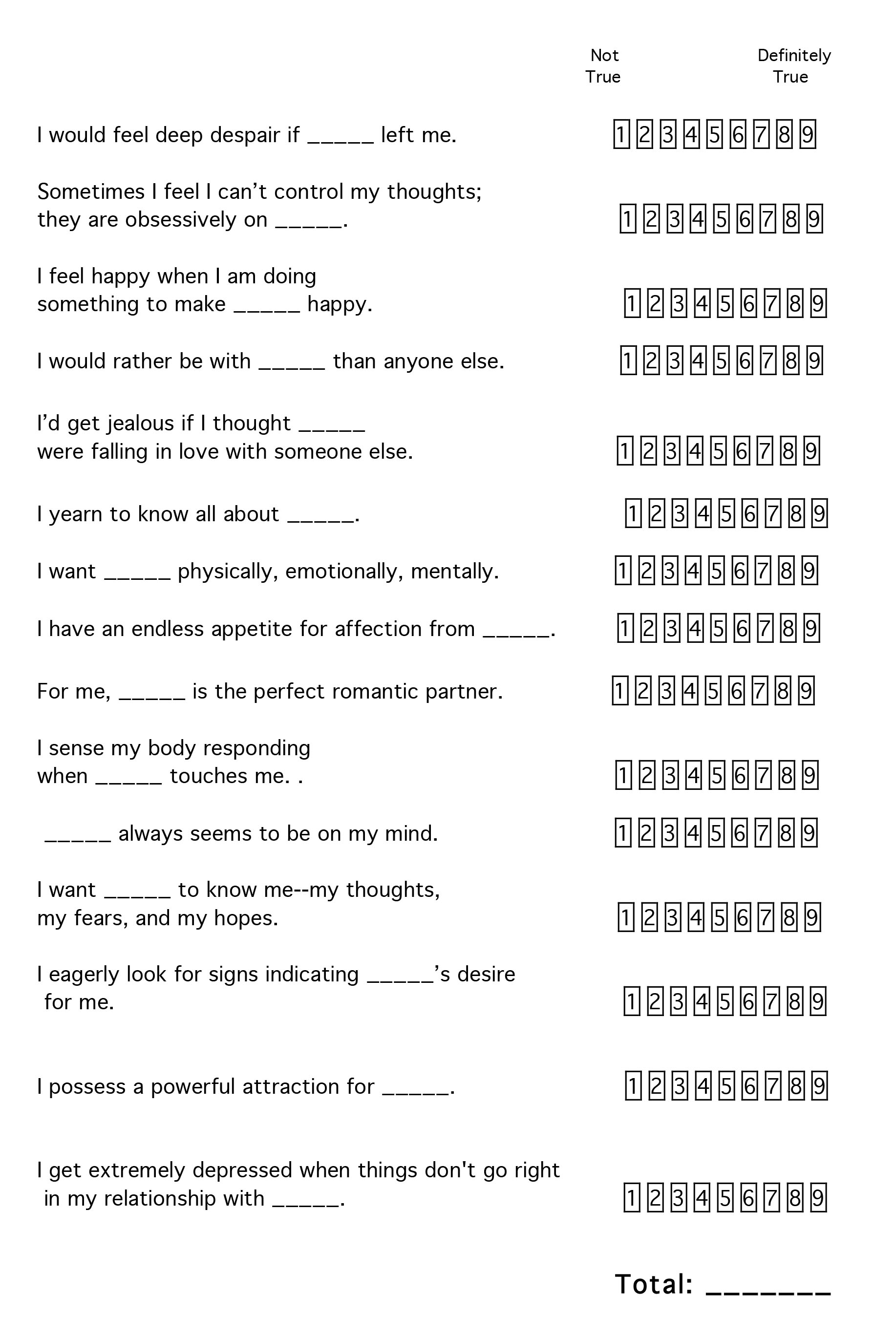

The Passionate Love Scale was designed to assess the cognitive, physiological, and behavioral indicants of such love. Below is a copy of the scale we have developed.

Instructions: We would like to know how you feel (or once felt) about the person you love, or have loved, most passionately. Some common terms for passionate love are romantic love, infatuation, love sickness, or obsessive love. Please think of the person whom you love most passionately right now. Try to describe the way you felt when your feelings were most intense. Answers range from (1) Not at all true to (9) Definitely true.

Results:

• 106-135 points = Wildly, even recklessly, in love.

• 86-105 points = Passionate, but less intense.

• 66-85 points = Occasional bursts of passion.

• 45-65 points = Tepid, infrequent passion.

• 15-44 points = The thrill is gone.

The PLS has been translated by scholars all over the world: in Brazil, France, Germany, Holland, India, Indonesia, Iran, China, Italy, Japan, Korea, Pakistan, Peru, Poland, Portugal, Russia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and Turkey. And as to the nature of love? We had plenty of questions:

1. What is passionate love? A cognition? An emotion? A behavior? All three?

2. Why are people in the throes of love so crazed, so unable to think of anything else? Why are their feelings so tumultuous—traveling from elation to blackest despair in a matter of seconds? Why are they willing to take such stunning risks for love?

3. Is passionate love a cultural universal?

4. Are there some people who never fall in love?

5. Are passionate love and sexual desire the same thing—kissing cousins, so to speak—or are they different constructs?

6. Do men and women love with equal passion?

7. Are people with high self esteem more (or less likely) to fall in love?

8. In dating and marriage is there sort of a “mating marketplace”—i.e., with people pairing up with potential partners who possess attractiveness and mate appeal similar to their own? (Is it foolhardy to yearn for someone “out of your league,” or to settle, when you can obviously “do better”?)

9. How long do passionate and companionate love last?

We had no answers. Now we do. For answers, see ((In a nutshell, here are the answers: 1. All three. 2. That’s what makes us human. 3. Yes. 4. Yes, sad to say. 5. They are closely connected: kissing cousins. 6. Yes. 7. The data are mixed. 8. Yes. 9. Both decline slightly and equally over time. If you scored from 7-9: Bravo. 4-6: Typical! 1-3: You are in deep trouble.)).

What a change has occurred in 50+ years! Today, scholars from a variety of theoretical disciplines—social psychologists, neuroscientists, cultural psychologists, anthropologists, evolutionary psychologists, historians, and more—are addressing the same issues with which we struggled. They are employing an impressive array of new techniques as well, ranging from studying primates in the wild and in captivity to pouring over fMRIs on lovers, in the throes of passion or enduring devastating loss.

Love has also acquired a historical dimension, as historians study the love lives, not only of kings and queens, but those of regular folks as well. They are utilizing demographic data (marriage records, birth and death records, records of divorce), architecture, medical manuals, church edicts, legal records, song lyrics, and the occasional journal that floats to the surface like a long-lost treasure. We can now answer in some detail most of the questions we raised in the 1960s. Here, let us now consider the evidence in support of a few of our answers in more detail:

What is passionate love? A cognition? An emotion? A behavior? All three?

The earliest researchers, struggling to define love, tended to categorize it in ways that were familiar to them. Attitude scholars (like us) defined love as an attitude, chemists defined it as a chemical reaction, and the like. Emotions researchers, however, were already well aware that in the course of evolution, our ancestors had evolved “emotion packages” that included a constellation of components. The angry person possessed dark thoughts, felt furious, had strong physiological reactions, and yearned to lash out. So with love: it involves a variety of components, all working in synchrony.

Is passionate love a cultural universal?

Scholars like William Goode (1959) were scathing in their denunciation of Westerners’ idea that love was the sine qua non of marriage. Today, however, anthropologists, evolutionary psychologists, and social psychologists agree that passionate love is a cultural universal. William Jankowiak and Edward Fischer (1992), for example, searched for evidence of romantic love in a sampling of the tribal societies included in the Standard Cross-Cultural Sample. (The Sample contains ethnographic information on 186 cultural and pre-industrial areas of the world.)

The authors classified societies as to whether or not romantic love was present (or absent) on the basis of five indicators: (1) accounts depicting personal anguish and longing; (2) the existence of love songs or folklore that highlight the motivations behind romantic involvement; (3) elopement due to mutual affection; (4) native accounts affirming the existence of passionate love; and (5) the ethnographer’s affirmation that romantic love was present.

They found clear evidence of passionate love in almost all of the tribal cultures they studied. People in all cultures recognize the power of passionate love. In South Indian Tamil families, for example, a person who falls head-over-heels in love is said to be suffering from mayakkam—dizziness, confusion, intoxication, and delusion. The wild hopes and despairs of love are thought to “mix you up” (Trawick, 1990).

Culture can, of course, have a profound impact on people’s views of love, how susceptible they are to falling in love, with whom they tend to fall in love, their willingness to insist on marriage for love, and how their passionate affairs work out. Yet, a wide variety of studies document that the significant differences that once existed between Westernized, urban, modern, industrial societies and more traditional rural societies are disappearing, sometimes amazingly quickly.

These days, those interested in cross-cultural differences may only find them if they investigate the most underdeveloped, developing, and collectivist of societies—such as communities in Africa or Latin America, or the Arab countries (Egypt, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Saudia-Arabia, Iraq, or the U. A. E.). However, even in those countries, the winds of Westernization and change are blowing. For more information on the universality of love, see Hatfield, Rapson, & Martel (2007).

Neuro-biological perspectives

In 2000, two London neuroscientists, Andreas Bartels and Semir Zeki, set out to identify the brain regions associated with passionate love and sexual desire. The scientists put up posters around London, advertising for men and women who were “truly, deeply, and madly in love.” Seventy young men and women from 11 countries responded. Participants were asked to complete the Passionate Love Scale (PLS). Participants were placed in an fMRI (functional magnetic imagery) scanner.

This high-tech scanner constructs an image of the brain in which changes in blood flow (induced by brain activity) are represented as color-coded pixels. In the machine, Bartels and Zeki gave each participant a color photograph of their beloved to gaze at, alternating the beloved’s picture with pictures of a trio of casual friends. They then digitally compared the scans taken while the participants viewed their beloved’s picture with those taken while they viewed a friend’s picture, creating images that represented the brain regions that became more (or less) active in both conditions.

Not surprisingly, the Bartels and Zeki research sparked a cascade of fMRI research. Several findings from this flood of research are of interest:

(1) Neuroscientists have found that scores on the PLS are highly correlated with the intensity of lovers’ reactions to pictures of the beloved.

(2) Passion sparked increased activity in the brain areas associated with euphoria and reward. Most of the regions that were activated during the experience of romantic love were those that are active when people are under the influence of euphoria-inducing drugs such as opiates or cocaine. Apparently, both passionate love and those drugs activate a “blissed-out” circuit in the brain.

(3) The authors also found decreased activity in the areas associated with sadness, anxiety, and fear. Among the regions where activity decreased during the experience of love were zones previously implicated in the areas of the brain controlling critical thought. Apparently, once we fall in love with someone, we feel less need to assess critically their character and personality. (In that sense, love may indeed be “blind.”) For more information on this topic, see Hatfield & Rapson (2009).

In dating and marriage is there sort of a “mate marketplace”—i.e., with people pairing up with potential partners who possess attractiveness and mate appeal similar to their own?

In fairy tales, Prince Charming often falls in love with the scullery maid. In real life, however, dating couples almost always ends up with a “suitable” partner—which means the most appealing partner they can attract in a competitive dating market. As Goffman (1952) dryly observed:

“A proposal of marriage in our society tends to be a way in which a man sums up his social attributes and suggests that hers are not so much better as to preclude a merger” (p. 456).

Since the 1960s, scientists have conducted a flood of research documenting that people tend to pair up with romantic and sexual partners similar to themselves in physical attractiveness (see Hatfield, Forbes, & Rapson, 2012, for a review of this research.) Of course, in the dating and mating “marketplace,” physical appearance is not the only thing young people have to offer.

Equity theorists Hatfield, Walster, and Berscheid, (1978) assembled voluminous evidence documenting the critical importance of the dating “marketplace” in mate selection. Specifically, scholars find: Market considerations affect both gay and straight people’s romantic and sexual choices. Couples are likely to end up with someone fairly close to themselves in social desirability. Couples tend to be matched on the basis of self-esteem, looks, intelligence, education, mental and physical health (or disability). People rarely get matched up with someone who is either “out of their league” or “beneath them.”

It is in the early stages of dating or sexual relationships, of course, that considerations of the marketplace loom large. As couples become more committed to one another, love and compatibility become more important than “mate value”, and the “marketplace” diminishes in importance.

How long do passionate and companionate love last?

Passionate love is a fleeting emotion. It is a high, and one cannot stay high forever. Hatfield and her colleagues (2008) interviewed couples (dating couples, newlyweds, and long-married couples). They found that, as expected, passionate love decreased markedly over time. When asked to rate their feelings on a scale that included the responses “none at all,” “very little,” “some,” “a great deal,” and “a tremendous amount,” steady daters and newlyweds expressed “a great deal” of passionate love for their mates. However, starting shortly after marriage, passionate love was shown to steadily decline, with long-married couples admitting that they felt only “some” passionate love for each other.

Fortunately, there may be a bright side to this seemingly grim picture. Where passionate love once existed, companionate love sometimes takes its place. Companionate love is thought to be a gentle emotion, comprised of feelings of deep attachment, intimacy, and commitment. It is this kind of love that often keeps couples together.

In conclusion: Given the current popularity of research on passionate love among emotions researchers, it is obvious that in the next few years our understanding of love will increase. Given the societal changes, the context of love research is also bound to change. What is the impact of dating Web sites and speed dating on passion? What will be the impact on romantic commitment from sites like Zoosk, Badoo, and Tinder? They allow one, when chatting up a real, physically present date at a club, to search for someone better, for fun or sex, from across the room or down the block. What will be the impact on passion of made-to-order sex robots?

Asked in the form of serious play, these are just a few of the questions that can be generated by an awareness of the rapidly changing landscape of love. Love research has made remarkable progress in the past half-century, but research on that elusive and powerful emotion is obviously only just getting started.

References

Bartels, A. & Zeki, S. (November 27, 2000). The neural basis of romantic love. Neuroreport, 11, 3829-3834.

Goffman, E. (1972). The presentation of self in everyday life. University of Edinburgh, Social Sciences Research Centre: Edinburg.

Goode, W. J. (1959). The theoretical importance of love. American Sociological Review, 24, 38-47.

Hatfield, E., Forbes, M., & Rapson, R. L. (November/December 2012). Commentary: Marketing love and sex. Social Science and Modern SOCIETY: Symposium: Mating Game, 49, 506-511. doi: 10.1007/s12115-012-9593-1

Hatfield, E, Rapson, R. L., & Martel, L. D. (2007.) Passionate love and sexual desire. In S. Kitayama & D. Cohen (Eds.) Handbook of cultural psychology. New York: Guilford Press, pp. 760-779.

Hatfield, E. & Rapson, R. L. (2009). The neuropsychology of passionate love and sexual desire. In E. Cuyler and M. Ackhart (Eds.). Psychology of social relationships. Hauppauge, NY: Nova Science.

Hatfield, E. & Sprecher, S. (1986). Measuring passionate love in intimate relations. Journal of Adolescence, 9, 383-410.

Hatfield, E., Pillemer, J. T., O’Brien, M. U., & Le, Y. L. (June, 2008). The endurance of love: passionate and companionate love in newlywed and long-term marriages. Interpersona: An International Journal of Personal Relationships, 2, 35-64. http://www.interpersona.org/issues.php?section=viewfulltext&issue=3&area=14&id=int485ee26d5859b&fulltextid=14&idiom=1

Hatfield, E., Walster, G. W., & Berscheid, E. (1978). Equity: Theory and research. Boston: Allyn and Bacon. [ISBN: 0-205-05929-5].

Jankowiak, W. R. & Fischer, E. F. (1992). A cross-cultural perspective on romantic love. Ethology, 31, 149-155.

Trawick, M. (1990). Notes on love in a Tamil family. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.