Center for Social and Cultural Psychology

jozefien.deleersnyder@kuleuven.be

The same situation is often experienced differently by people from different socio-cultural backgrounds, and these emotional mismatches often bear negative consequences. For instance, when my Turkish Belgian friend Ayşe told me that her boss had broken his promise to grant her and her teammates a tenured contract, I thought she should be angry, stand up for herself and go argue with her boss – a pattern of emotion that was very much shared by her Belgian teammates and that reflected our concern with autonomy, fairness and individual rights. However, Ayşe herself did not feel that way: She also felt angry, for sure, but in addition she also felt ashamed (maybe she had fallen short?) and still experienced a lot of respect and closeness towards her boss – a pattern of emotion that prevented her from arguing with him and reflected her concern for their (hierarchic) relationship. Upon finding out how she felt, Ayşe’s Belgian teammates found her ‘weak’ and did not ask her to join for lunch the next couple of days, which, in turn, triggered Ayşe to doubt herself. As illustrated here, emotional mismatches in everyday situations may not only hamper people’s social interactions, but may also – when occurring repeatedly – impact their well-being and thriving in a society.

Over the past ten years, I have addressed several research questions that relate to the example of Ayşe and that, together, aim to understand the interplay between culture, emotion and well-being. Firstly, and building on the comprehensive evidence that there are systematic cultural differences in emotional experience (e.g., Mesquita, 2003; Mesquita, De Leersnyder, & Boiger, 2016; Tsai & Clobert, 2019), I investigated if the emotional patterns of immigrant minorities can change upon repeated exposure to and engagement in the majority context and thus, if Ayşe’s emotions would acculturate. Secondly, and extrapolating from the literature on emotional similarity in relationships and teams (e.g., Anderson, Keltner, & John, 2003; Gonzaga, Campos & Bradbury, 2007; Totterdell, 2000), I explored if people would benefit from being emotionally similar to others in their cultural context and thus, if Ayşe’s (repeated) experiences of emotional (mis)fit would be associated with her relational and psychological well-being. Most recently, I started tapping into the question how emotional fit may come about in intercultural interactions,thereby addressing i) if the increased salience of typically Belgian cultural concerns (e.g., the concern for autonomy) shapes Ayşe’s emotional patterns, and ii) how she might learn new emotional patterns through observing, mimicking and negotiating them with her Belgian teammates. Together, these research lines provide evidence for the socio-cultural shaping of emotional experience, and put forward a contextual and dynamic socio-cultural fit perspective on emotion.

Below, I describe each of these three research lines in more detail, after which I will highlight how they provide more general insights for emotion researchers. Yet first, I will spend a few words on how I understand emotional experience from a cultural psychological perspective (see also De Leersnyder, Boiger, & Mesquita, 2020).

Emotions as Acts of Making Meaning

Among emotion scholars, there is quite some consensus that emotions i) occur when something is relevant to our concerns – i.e., the values, goals and needs that are salient at a particular moment in time (Frankfurt, 1980; Frijda, 1986), and ii) reflect how people evaluate a particular situation (appraisal) and how they aim to act upon it (action tendency). For instance, ‘anger’ is usually considered to reflect that someone else is to be blamed for a negative outcome (i.e., appraisal) to something you care about (i.e., concern), as well as characterized by an urge to (re-)gain control, influence and correct the other’s behavior (i.e., action tendency; Frijda, Kuipers, & Schure, 1989; Stein, Trabasso, & Liwag, 1993). Likewise, ‘shame’ is usually characterized by an appraisal of the situation as if you fell short with respect to social norms you aim to adhere to, as well as by an action tendency to restore social relationships (e.g., Keltner, & Buswell, 1997). As such, emotional experiences can be considered as acts of making meaning: They not only signal what people find important, but also reflect which stances they take in (these usually social) situations and relationships (Mesquita, 2010; Solomon, 2004). [1]

Nevertheless, there is a fairly heated debate among emotion scholars about the extent to which emotions are culturally shaped. Yet, from the above sketched definition of emotions as acts of making meaning, it may be clear why we would expect to find evidence for the latter option. If there is substantial cultural variation in the things people find important (i.e., their values, moral concerns; e.g., Schwartz, 1992), as well as in the stances they usually take in situations and relationships (i.e., their models of self and relating; e.g., Markus & Kitayama, 1991), then the ‘core ingredients’ of emotional experience are ‘cultured’. Consequentially, we may expect systematic cultural variation in emotional experience that can be understood from both the importance of specific cultural concerns and the typical ways of being and relating.

Over the past two decades, evidence for this cultural alignment of emotions has accumulated (for reviews, see De Leersnyder, Boiger & Mesquita, 2020; Mesquita, 2003; Tsai & Clobert, 2019). Specifically, so-called autonomy-promoting (or disengaging) emotions like ‘anger’ that highlight a person’s independence and separateness from others, seem to be more intense when people perceive a situation to touch upon self-focused concerns, such as those for success and showing your ambition (De Leersnyder, Kuppens, Koval & Mesquita, 2017). In contrast, so-called relatedness-promoting (or engaging) emotions like ‘shame’ that highlight a person’s interdependence and connectedness with others, seem to be more intense when people perceive a situation to touch upon other-focused concerns, such as those for helping others and being loyal (De Leersnyder et al., 2017). Thus, as there is cultural variation in the importance of these concerns, the frequencies and intensities with which people experience certain types of emotion may differ accordingly. Indeed, it has been found that autonomy-promoting emotions like ‘anger’ are more prevalent in Western European and North American middle class contexts that emphasize autonomy and success and that define a good person as being independent, autonomous and standing up for oneself (e.g., Boiger, Mesquita, Uchida, & Feldman Barrett, 2013; Kitayama, Mesquita, & Karasawa, 2006). In contrast, relatedness-promoting emotions like ‘shame’ are more prevalent in many East Asian, Mediterranean and working-class contexts that emphasize community and connectedness and that define a good person as being interdependent, related and respecting / maintaining hierarchy and harmony (e.g., Boiger et al., 2013; Kitayama et al., 2006). Hence, the frequencies and intensities with which people experience emotions can be understood from differences in both their cultural concerns and typical ways of being and relating.

Taken together, a definition of emotions as (collaborative) acts of making meaning in and upon the world, helps us understand why there is cultural variation in emotional experience. This, in turn, sets the scene for my research on emotional acculturation and emotional fit with context, which I’ll describe below.

Can Emotional Patterns Change Upon Engaging in Another Cultural Context?

In a first research line, I address if and how people’s patterns of emotion – i.e., the patterns of intensities with which they experience a set of emotions in response to a particular situation – change upon engaging in another cultural context. In other words, I study if there is emotional acculturation.[2]

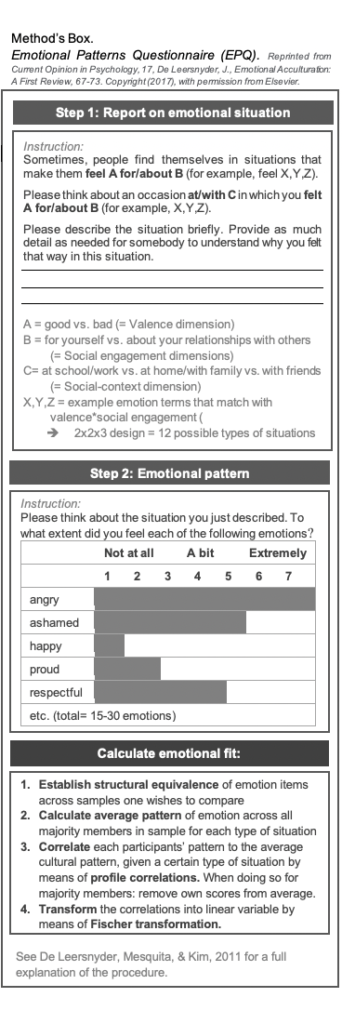

There are two prerequisites to study emotional acculturation, though. First, there needs to be cultural variation in emotional experience to begin with and hence different cultural contexts need to be characterized by different emotional patterns. Second, people engaging in the same cultural context need to be more likely to experience similar patterns of emotion than people engaging in different socio-cultural contexts. As outlined above, the literature provides extensive support for the first prerequisite; one of our own studies yielded support for the second one. Specifically, in that study (reported in De Leersnyder, 2014) we administered the Emotional Patterns Questionnaire (EPQ; De Leersnyder, Mesquita, & Kim, 2011) among majority members of European American, Korean, Belgian and Turkish cultural groups. Based on these data, we then calculated average emotional patterns for each cultural group*type of situation. By means of profile correlations we finally established each individual participant’s level of emotional fit with both their own and another cultural group’s average emotional pattern for the corresponding situation (see Methods Box for the full procedure). Across all four samples, we found that participants’ fit with their own culture’s average patterns of emotion was higher than their fit with another culture’s average patterns (De Leersnyder, 2014). People engaging in the same cultural context are thus more likely to experience similar patterns of emotion, which fulfills the second prerequisite to study emotional acculturation.

Turning to the actual study of emotional acculturation, we have conducted several studies that made use of the EPQ and method outlined above to establish participants’ emotional fit with the respective majority group. The first two studies included Korean American and Turkish Belgian minority adults as well as their majority counterparts (De Leersnyder et al., 2011, Study 1, 2 and 2a); the third one included a large, representative sample of minority and majority youth in Belgium (Jasini, De Leersnyder, Phalet, & Mesquita, 2019). All three studies provided evidence for emotional acculturation. Specifically, we found that minorities’ levels of emotional fit with the majority were significantly higher if they i) belonged to a later generation (i.e., second, third) than to the first generation; ii) had spent more years in the majority culture; iii) had migrated at a younger age and iv) reported more daily social contacts with majority members. Together, these studies suggest that although different upon arrival in a novel cultural context, immigrant minorities’ patterns of emotional experience may become similar to those of the majority upon engaging with them.

Some recent extensions of the nationally representative study on minority youth in Belgium (led by Dr. Jasini) further illuminate this association between social contact and emotional fit. A first extension moves beyond minorities’ self-reported contact with majority members by operationalizing it as bidirectional intercultural friendship ties in social networks embedded in classrooms. These data revealed that minority youths’ levels of emotional fit were higher if their social networks counted more bidirectional friendship ties with majority members and if more majority members nominated them as their friend (Jasini, et al., submitted).

A second extension moves beyond the above-reported cross-sectional inferences by collecting two more waves of data, each with one year apart. Cross-lagged as well as growth-curve analyses yielded that i) minority youth who reported more social interactions with majority peers had higher levels of emotional fit the subsequent year and ii) minorities’ levels of emotional fit in one year positively predicted their number of majority friends the next year (Jasini, De Leersnyder, Phalet & Mesquita, in preparation). Thus, although social contact may be driving emotional change, there is a positive feedback loop between emotional fit and social contact over time.

Similar evidence for the impact of social contact on emotional fit was found in two studies that explored to what extent minorities maintain their typical heritage emotional patterns. Specifically, we calculated to what extent our Korean American and Turkish Belgian participants fit with the average patterns of their respective heritage cultural context as comprised by responses of monocultural Koreans and Turks (De Leersnyder, Kim & Mesquita, 2020). We found that immigrant minorities’ emotional fit with their heritage culture was lower than that of heritage members themselves, but at a roughly equal level as their majority culture fit (which is in sharp contrast to monoculturals who mostly fit their own culture average patterns; cfr. supra). Moreover, it was higher if they reported to spend more time with heritage culture friends and if they interacted in heritage culture settings such as their home. Combined, these findings suggest that minorities’ heritage emotional patterns can be maintained through heritage cultural friendships and are not overwritten by the newly acquired emotional patterns; minorities may simply experience different patterns of emotion depending on their context of interaction (with home vs. school contexts reflecting heritage vs. majority cultures, respectively).

In sum, this line of research thus established first evidence for the idea that Ayşe’s emotional patterns may acculturate. Upon being exposed to the Belgian cultural context and having more social interactions with Belgian majority members – and especially with majorities who consider her as a friend – Ayşe’s patterns of emotion may, over time, come to be more similar to those of her Belgian teammates. Yet, as she interacts with Turkish friends, Ayşe may also maintain emotional fit to her Turkish heritage cultural patterns – patterns that are activated most when she’s engaging in heritage culture settings, such as at home. Emotional acculturation may thus be a bi-dimensional process that not only is driven by cultural engagement and social contact, but that is also context dependent.

Is Cultural Fit in Emotions Rewarding?

There is clear evidence of emotional acculturation. Yet, is it also beneficial to undergo changes in one’s emotional patterns such that one comes to fit in emotionally? For roommates, romantic couples and teammates this seems to be the case. For instance, higher emotional similarity among roommates is associated with higher closeness, trust, and likelihood to remain friends (Anderson, et al., 2003); among romantic couples, is it is associated with higher relationship satisfaction and a better quality of the relationship itself (e.g. Anderson et al., 2003; Gonzaga, et al., 2007). And, emotionally fitting teams and groups not only tend to be closer, happier and more identified than more divergent groups (e.g., Delvaux, Meeussen & Mesquita, 2015), but are also characterized by improved cooperation and decreased conflict (Barsade, 2002). Therefore, we may expect that emotional fit with one’s culture bears positive consequences as well: interaction partners may respond more positively to one another when there is emotional similarity (Szczurek, Monin, & Gross, 2013), which may lower their stress during the interaction (Townsend, Kim, & Mesquita, 2014) and increase mutual understanding and cooperation (Fisher & Manstead, 2016). In the long-run, these repeated positive interpersonal interactions that also instigate experiences of ‘feeling right’, may translate into both higher relational (i.e., satisfaction with relationships) and psychological well-being (i.e., lower depression).

To test this hypothesis, we conducted a series of studies that linked majority members’ fit with their own culture’s normative patterns of emotion to their levels of well-being (De Leersnyder, Kim, & Mesquita, 2015; De Leersnyder, Mesquita, Kim, Eom, & Choi, 2014). We focused on European American, Korean and Belgian cultural contexts as they differ profoundly in their cultural models of self and relating, allowing us to test whether associations would be similar or different across cultural contexts. To capture emotional fit, we again administered the EPQ and followed the procedure outlined above to calculate participants’ fit with the typical patterns of their own culture; to capture well-being, we administered the World Health Organization’s Quality of Life Scale that taps into both relational and psychological well-being and has been validated across many cultural contexts (Skevington, Lotfy, & O’connell, 2004).

When predicting relational well-being, we found similar results across the three samples: well-being was higher to the extent that participants fitted better with their own culture’s normative patterns of emotion in relationship-focused (i.e., socially engaging) situations (De Leersnyder et al., 2014). When predicting psychological well-being, we found a consistent, yet culturally varying pattern of results: well-being was higher to the extent that participants fit better with their own culture’s normative patterns of emotion in those situations that afford the realization of the cultural model of self and relating (De Leersnyder et al., 2015). Specifically, European Americans’ psychological well-being was higher upon fitting in with autonomy-promoting (i.e. disengaging) situations at work – situations that primarily afford (both positive and negative) autonomy-promoting emotions such as pride and anger, and that, thereby, afford the realization of the European American cultural mandate to be autonomous, independent, successful and unique, especially at work (e.g., Kitayama & Imada, 2010; Sanchez-Burks, Uhlmann, & Carlyle, 2013). In contrast, Koreans’ psychological well-being was higher upon fitting in with relatedness-promoting (i.e. engaging) situations at home only – situations that primarily afford (both positive and negative) relatedness-promoting emotions such as closeness and shame and that, thereby afford the Korean cultural mandate of being closely related to family members (Markus & Kitayama, 1991; Neuliep, 2011; Rothbaum et al., 2000). Finally, Belgians’ psychological well-being was higher upon fitting in with both autonomy-promoting and relatedness-promoting situations, regardless of the valence of the situation or the context – a finding that can be interpreted as being in line with the Belgian cultural model of egalitarian autonomy in which autonomy is valued as long as it does not jeopardize relatedness (e.g., Boiger, De Deyne, & Mesquita, 2013). Thus, experiencing emotional fit with culture in situations that are about relationships is linked to higher satisfaction with one’s social relationships, while experiencing cultural fit in situations that are culturally central is linked to better psychological well-being.

In sum, evidence among monoculturals shows that emotional fit with culture may be beneficial. Future studies should explore whether similar patterns of results hold among immigrant minorities like Ayşe, testing if increases in her emotional fit with the majority lead her to experience smoother social relationships with Belgians, as well as higher levels of self-esteem and lower levels of depression (see Consedine, Chentsova-Dutton, & Krivoshekova, 2014 for a first study predicting immigrant women’s somatic health from their fit with the majority ways to express emotion). Yet, since Ayşe does not only navigate Belgian majority contexts (e.g., at work) but also Turkish heritage contexts (e.g., at home) throughout her daily life, we may expect that her well-being is not only contingent upon her emotional fit with typical Belgian emotional patterns in majority contexts, but also upon her emotional fit with typical Turkish emotional patterns in heritage contexts.

How Does Emotional Fit Come About?

In my most recent line of research, I have started to tap into the question of how emotional fit may come about in intercultural interactions, thereby focusing on both the processes that activate existing emotional patterns and on the processes that instigate the internalization of new emotional patterns. Related to the first type of processes, I investigated if biculturals would experience different patterns of emotion given the exact same situation, depending on which concerns are most salient in their specific cultural context. If concerns indeed constitute the backdrop against which we make meaning (cfr. supra), and if different cultural contexts are characterized by different concerns, then these could activate different ways of making sense of the same situation and hence activate different patterns of emotional experience.

Specifically, I conducted a field experiment with Turkish Belgian biculturals for whom it is likely that they had internalized both the typical Belgian and Turkish patterns of emotion (De Leersnyder & Mesquita, submitted). I randomly assigned them to either a Belgian cultural context (i.e., neighborhood center where language of interaction and interaction partners were Flemish-Belgian) or a Turkish cultural context (i.e., room attached to neighborhood mosque where language of interaction and interaction partners were Turkish). In either context, participants interacted with a same-gender confederate who enacted extensively pre-tested scenarios that could be interpreted as either clear-cut violations of autonomy (i.c., fairness, equal rights) or community (i.c., respect, hierarchy) concerns, or as ambiguous violations that could be equally well interpreted as a violation of autonomy or community concerns. Building on the literature, I expected that clear-cut situations would be associated with culturally similar patterns of emotion, with autonomy violations being characterized by ‘anger’ and community violations being characterized by ‘contempt’ (Rozin et al., 1999). In addition, and building upon the idea that Belgian contexts highlight autonomy concerns more than community concerns whereas the opposite is true for Turkish contexts (Shweder, Munch, Mahapatra, & Park, 1997), I expected that ambiguous situations would be interpreted in line with the most salient concerns and hence, be characterized by different patterns of emotion in the Belgian versus Turkish context.

All interactions were video-taped and the 2-minute intervals after each violation were coded for biculturals’ behavioral cues of ‘anger’ and ‘contempt’ by a multicultural team of three hypotheses-blind coders according to a scheme that included both FACS and SPAFF codes (Ekman & Friesen, 1978; Gottman, McCoy, Coan, & Collier, 1996). The results largely confirmed my expectations: Biculturals’ emotional responses to clear-cut violations were in line with the finding by Rozin and colleagues (autonomy = ‘anger’ > ‘contempt’; community = ‘contempt’ ≥ ‘anger’), while their responses to ambiguous violations yielded different emotional patterns that were in line with the contexts’ most salient concerns. In the Belgian context, biculturals’ emotional responses were dominated by ‘anger’ cues – a pattern of emotion that mirrored the one found in the clear-cut autonomy violations. In contrast, in the Turkish context, biculturals responded with equal ‘anger’ and ‘contempt’ upon ambiguous situations – a pattern that was clearly different from the one obtained in Belgian contexts and that was more in line with their responses upon clear-cut community violations (De Leersnyder & Mesquita, submitted). Therefore, the current experiment suggests that cultural differences in the salience of (autonomy vs. community) concerns may guide biculturals’ interpretations of (ambiguous) situations and, therefore, yield different patterns of emotion.

Applying the above-described findings to emotional acculturation yields three novel insights. Firstly, if emotions are systematically linked to concerns, we may come to understand emotional acculturation as a shift in people’s concerns and thus in the backdrop against which they make meaning of everyday situations. Secondly, if different cultural contexts promote different concerns, minorities may experience heritage versus majority emotional patterns (and fit) depending on their socio-cultural context of interaction and the concerns that are most salient within that context. Finally, if we aim to understand how immigrant minorities come to acquire new emotional patterns in social interactions with majority peers, we may want to focus on processes that reflect the negotiation of meanings.

This brings me to the second part of this research question: what are the exact micro-processes that instigate emotional fit in intercultural interactions, and that may, over time, account for enduring changes in emotional patterns and thus for emotional acculturation? Do immigrant minorities acquire new emotional patterns by simply observing emotional reactions of Belgian majority members? Or do immigrant minorities need to mimic majority members’ emotional patterns before they can come to internalize these new patterns? Or does internalization require an even more active negotiation of emotional meanings, such as in the process of grounding through which people establish (new) common ground with one another (see De Leersnyder, Mirzada, Neo & Dinç, 2020 for a first study on this, and Kashima, Klein & Clark, 2007 for a theoretical explanation of the grounding process). Currently, we are in the final stages of collecting data to shed light on how each one of these micro-processes may instigate emotional fit in intercultural interactions.

In sum, this research line points to the possibility that Ayşe may learn new emotional patterns through observing, mimicking and negotiating emotional meanings with her Belgian teammates and friends. Through these processes, both her heritage and new emotional patterns may come to co-exist and once internalized, Ayşe may switch between them depending on whether she interacts in Belgian versus Turkish cultural contexts that promote different types of concerns, which constitute the backdrop against which she makes meaning.

Insights for Emotion Researchers and Future Directions

The results of these three research lines not only shed light on the phenomenon of emotional acculturation, but also bear several insights for emotion psychology more generally. Firstly, our findings point to a systematic co-occurrence of emotions and concerns in both monoculturals (De Leersnyder et al., 2017) and biculturals (De Leersnyder & Mesquita, submitted). This co-occurrence challenges the negligible role that most emotion theories assign to concerns. In fact, although concerns are considered crucial to emotion elicitation – an emotion cannot be elicited without a situation relevant to one’s concerns – it is tacitly assumed that concerns are mutually interchangeable to the nature of the emotional experience – that is, that the content of the concern does not matter for which emotion we experience (e.g., Frijda, 1986; Scherer, 2005). For instance, in order to experience ‘anger’ most emotion theories propose that the situation has to be relevant to one’s concerns (i.e., appraisal of goal relevance) but do not specify which type of concern should be relevant (e.g., autonomy/self-focused vs. community/other-focused concerns?), thereby neglecting the content of the concern (i.e., what the person cares about). The current findings argue for a different perspective in which the content of concerns does importantly shape experience: They show how (culturally) salient concerns constitute the backdrop against which people make meaning during emotional episodes. Hence, “different cultural contexts may encourage certain themes [– i.e., goals, concerns –] over others [and may, therefore…] give rise to systematic cultural variation in emotional experience” (Kitayama et al., 2006, p. 890). This novel perspective on the role of concerns not only triggers novel endeavors into the processes that link concerns to emotions (e.g., via the activation of certain sets of appraisals or action tendencies; see De Leersnyder et al., 2017), but also highlights once more that emotions are, at their core, acts of making meaning.

Secondly, studying emotional change during the process of acculturation can be seen as a naturally occurring quasi-experiment testing whether changes in cultural contexts bring about changes in emotional patterns. Our finding, then, that people’s emotional patterns change upon engaging in a new/other socio-cultural context, challenges the idea that the links between antecedent events and (distinct) emotions are either hardwired through evolution (e.g., Ekman, 1992) or carved in stone during childhood. Rather, it suggests that there is plasticity in people’s emotional life long after initial socialization. When people experience which emotions is continuously shaped by their (changing) cultural engagements. In this way, the study of emotional acculturation may contribute to the long-standing debate on the role of culture in emotion.

Thirdly, our findings lend further empirical support to a socio-dynamic perspective on emotions (e.g., Boiger & Mesquita, 2012; Mesquita & Boiger, 2014), arguing that emotions emerge from social interactions such that “social interaction and emotions form one system of which the parts cannot be separated” (Mesquita & Boiger, p. 1). Specifically, our finding that (repeated) social contact and friendships are driving changes in emotional patterns highlight that social interactions are inherently shaped by culture and may, therefore, embody reinforcement structures and affordances that systematically promote or constrain the experience of certain emotions over others. Hence, our social interactions may instigate different emotional patterns and it is thus during social interactions that (new) patterns of emotional experience are (re)calibrated to (new) cultural standards, whether this occurs through observation, mimicking or grounding. Relatedly, our initial evidence for the co-existence and context-dependency of heritage and majority emotional patterns in biculturals suggests that one’s social context of interaction may shape/activate one’s patterns of emotional experience. Once acquired, emotional patterns are thus not omnipresent, but activated by people’s specific contexts of interaction. Together, these findings hint at not only the emergent nature of emotions, but also at their dynamism.

Fourthly, our methodological innovation to capture people’s emotional fit with culture allows for another perspective on cultural differences in emotion: away from mean score differences between cultural groups and toward modeling variability in adherence to (descriptive) cultural norms among people within the same cultural group. Indeed, people are not carbon copies of their culture’s prototypical member and operationalizing individual differences as such may do more justice to (implicit) theoretical perspectives in cultural psychology (Chentsova, De Leersnyder, & Senzaki, forthcoming). In addition, this cultural fit approach to emotion may provide a more nuanced understanding of the potential benefits of experiencing certain emotions over others. Rather than that certain emotions per se are (cross-culturally) associated with psychological and relational well-being, it may be that well-being is linked to one’s socio-cultural fit in emotional experience for specific (culturally central) types of situations. Indeed, experiencing culturally normative emotions may promote acceptance and belonging as it helps one be the type of person and engage in relationships that are valued in one’s cultural context. Hence, emotions and emotional acculturation can be considered gateways into (minority) belonging and well-being.

Finally, and despite the insights put forward above, I wish to mention how the study of emotional acculturation is only in its infancy. Future research should, for instance, focus on acculturation in other aspects of emotional functioning than people’s self-reported experience; one example is a study by Consedine, Chentsova-Dutton & Krivoshekova (2014) on acculturation in minority women’s emotional expressivity, another is a study by Bjornsdottir and Rule (2016) on the acculturation of minorities’ ability to understand emotions from the ‘reading the mind in the eyes-task’. Future work could also explore the specific content of acculturative changes in emotion. To date, we don’t know if acculturation affects specific (sets) of emotion(s) only or if it affects emotional patterning as a whole. Similarly, we can only guess if higher well-being is linked to acculturation in specific (sets) of emotion(s) or to acculturation in the co-occurrence and/or patterning of emotion. Moreover, and as outlined above, we have only begun to study the specific mechanisms underlying emotional change. Future studies should thus continue to investigate how people’s emotional systems get recalibrated during close, and meaningful (intercultural) interactions.

Acknowledgements

I would like to take this opportunity to highlight how my endeavors into the study of emotional acculturation have always been embedded in teamwork. As said by many others before, “Every single-author paper is a lie” – and just so is this piece for Emotion Researcher. All work I’ve described here is the outcome of tremendous team efforts, as well as profound and trusting collaborations with my mentors, my graduate and undergraduate students, anonymous reviewers, funding agencies, critical but constructive colleagues and friends, and the approximately 10,000 people who have taken the time to participate in our research. Contrary to some popular beliefs about science, my ideas have never sparked off in isolation but emerged during interactions with my colleagues, the data, and the participants who provided them. Also, these ideas were never ‘usable’ from the start, but needed time to ripen. The above described insights are thus the fruit of a truly interdependent and relatively slow scientific undertaking. I have been extremely lucky to have been surrounded by so many supportive and constructive colleagues in a safe and patient research atmosphere that trusted this slow and profound science. It is my sincere wish that any reader of this piece may be as lucky as I have been in this regard.

References

Anderson, C., Keltner, D., & John, O. P. (2003). Emotional convergence between people over time. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 1054-1068.

Barrett, L. F. (2017). How emotions are made. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Barsade, S. G. (2002). The ripple effect: Emotional contagion and its influence on group behavior. Administrative Science Quarterly, 47, 644-675.

Bjornsdottir, R. T., & Rule, N. O., (2016). On the relationship between acculturation and intercultural understanding: Insight from the Reading the Mind in the Eyes test. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 52, 39-48.

Boiger, M., Ceulemans, E., De Leersnyder, J., Uchida, Y., Norasakkunkit, V., & Mesquita, B. (2018). Beyond Essentialism: Cultural Differences in Emotions Revisited. Emotion, 18(8), 1142-1162. doi: 10.1037/emo0000390.

Boiger, M., De Deyne, S., & Mesquita, B. (2013). Emotions in “the world”: Cultural practices, products, and meanings of anger and shame in two individualist cultures. Frontiers in Psychology 4(867).

Boiger, M., & Mesquita, B. (2012). The construction of emotion in interactions, relationships, and cultures. Emotion Review, 4,221-229.

Boiger, M., Mesquita, B., Uchida, Y., & Barrett, L. F. (2013). Condoned or condemned: The situational affordance of anger and shame in Japan and the US. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 39, 540–553.

Chentsova-Dutton, Y. E., De Leersnyder J., & Senzaki, S., (forthcoming). The Psychology of Cultural Fit: Introduction to the Research Topic. Frontiers in Psychology.

Consedine, N.S., Chentsova-Dutton, Y. E. & Krivoshekova, Y. S. (2014). Emotional acculturation predicts better somatic health: Experiental and expressive acculturation among immigrant women from four ethnic groups. Journal of Social Clinical Psychology, 33(10), 867–889.

De Leersnyder, J. (2014). Emotional Acculturation. Doctoral dissertation. KU Leuven, Belgium.

De Leersnyder, J., (2019). Emotional Enculturation and Acculturation: Insights from Culture and Emotion Research for Affective Social Learning. In D. Dukes & F. Clement (Eds.), Affective Social Learning. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

De Leersnyder, J., Kim, H., & Mesquita, B. (2015). Feeling right is feeling good: Psychological well-being and emotional fit with culture in autonomy-vs. relatedness-promoting situations. Frontiers in Psychology, 6: 630.

De Leersnyder, J., Kim, H., & Mesquita, B. (2020). My emotions belong here and there: Extending the phenomenon of emotional acculturation to heritage cultural contexts. Manuscript under review.

De Leersnyder, J., Koval, P., Kuppens, P., & Mesquita, B. (2017). Emotions and concerns: Situational evidence for their systematic co-occurrence. Emotion, 18(4), 597-614.

De Leersnyder, J., Boiger, B. & Mesquita, B. (2020). What has culture got to do with emotions? A lot! In M. Gelfand, Y-Y. Hong and C.H. Chui. (Eds.), Advances in Cultural Psychology (Vol. 8). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

De Leersnyder, J., & Mesquita, B. (submitted). Emotional Frame-switching: How biculturals’ make their emotions fit the cultural context. Manuscript submitted for publication.

De Leersnyder, J., Mesquita, B., & Kim, H. (2011). Where do my emotions belong? A study of immigrants’ emotional acculturation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 37(4), 451-463.

De Leersnyder, J., Mesquita, B., Kim, H., Eom, K., & Choi (2014). Emotional Fit with Culture: A Predictor of Individual Differences in Relational Well-being. Emotion, 14(2), 241-245.

De Leersnyder, J., Mirzada, F., Neo, S., & Dinç, G. (2020). Grounding emotions in intercultural interactions: a social experiment on the negotiation of emotional meaning. Manuscript in preparation.

Delvaux E, Meeussen L and Mesquita B (2015) Feel like you belong: on the bidirectional link between emotional fit and group identification in task groups. Frontiers in Psychology 6:1106. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01106

Ekman, P. (1992). An argument for Basic Emotions. Cognition and Emotion 6 (3), 169-200.

Ekman, P. & Friesen, W. (1978) Facial Action Coding System: A Technique for the Measurement of Facial Movement. Consulting Psychologists Press, Palo Alto.

Fischer, A. H., & Manstead, A. S. R. (2016). Social functions of emotion and emotion regulation. In L. F. Barrett, M. Lewis, & J. M. Haviland-Jones (Eds.), Handbook of emotions (4th ed., pp. 424–439). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Frankfurt, H. G. (1988). The importance of what we care about. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Frijda, N. H. (1986). The emotions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gottman, J. M., McCoy, K., Coan, J., & Collier, H. (1996). The Specific Affect Coding System (SPAFF). In J.M. Gottman (Ed.), What Predicts Divorce: The Measures. New York, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Jasini, A., De Leersnyder, J., Kende, J. Gagliolo, M., Phalet, K., & Mesquita, B. (submitted). Emotional Acculturation in the classroom: a social network study. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Jasini, A., De Leersnyder, J., Phalet, K., & Mesquita, B. (2019). Tuning in emotionally: Associations of cultural exposure with distal and proximal emotional fit in acculturating youth. European Journal of Social Psychology, 49, 352–365.

Jasini, A., De Leersnyder, J., Phalet, K., & Mesquita, B. (in preparation). Emotional acculturation: A three year longitudinal study on minority youth in Flanders. Manuscript in preparation.

Keltner, D., & Buswell, B. N. (1997). Embarrassment: Its distinct form and appeasement functions. Psychological Bulletin, 122, 250–270. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.122.3.250

Kitayama, S., & Imada, T. (2010). Implicit independence and interdependence: A cultural task analysis. In B. Mesquita, L. F. Barrett, & E. R. Smith (Eds.), The mind in context (pp. 174-200). New York, NY: Guilford.

Kitayama, S., Mesquita, B., & Karasawa, M. (2006). The emotional basis of independent and interdependent selves: Socially disengaging and engaging emotions in the US and Japan. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91(5), 890-903.

Kashima, Y., Klein, O., & Clark, A.E. (2007). Grounding: Sharing Information in Social Interaction. In K. Fiedler (Ed), Social Communication (pp. 27-78). Psychology Press.

Lazarus, R. S. (1991). Emotion and adaptation. New York: Oxford University Press.

Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review 98, 224–253.

Mesquita, B. (2003). Emotions as dynamic cultural phenomena. In R. Davidson, H. Goldsmith, & K. R. Scherer (Eds.), The handbook of the affective sciences (pp. 871-890). New York: Oxford University Press.

Mesquita, B. (2010). Emoting: A contextualized process. In Mesquita, B., Barrett, L. F., Smith, E.R. (Eds.). The Mind in Context (pp.83-104). New York: Guilford Press.

Mesquita, B., & Boiger, M. (2014). Emotions in Context: A Sociodynamic Model of Emotions. Emotion Review, 6(4), 298–302. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073914534480.

Mesquita, B., De Leersnyder, J., & Boiger, M. (2016). The cultural psychology of emotion. In L. F. Barrett, M. Lewis, & J. Haviland-Jones (Eds.), Handbook of emotions (4th ed., pp. 493–511). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Neuliep, J. W. (2011). Intercultural Communication: A Contextual Approach (5th Ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Parkinson, B. (2019). Heart to heart. How your emotions affect other people. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Redfield, R., Linton, R. & Herkovits, M. (1936). Memorandum for the study of acculturation. American anthropologist, 38, 149-152

Rothbaum, F. M., Pott, M., Azuma, H., Miyake, K., & Weisz, J. R. (2000). The development of close relationships in Japan and the United States: Paths of symbiotic harmony and generative tension. Child Development, 71(5), 1121–1142.

Rozin, P., Lowery, L., Imada, S., & Haidt, J. (1999). The CAD triad hypothesis: A mapping between three moral emotions (contempt, anger, disgust) and three moral codes (community, autonomy, divinity). Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76, 574−586.

Sanchez-Burks, J. & Uhlmann, E.L. (2014). Outlier nation: the cultural psychology of American workways. In Masaki Yuki & Marilynn Brewer (Eds.), Culture and group processes (pp. 121-142). Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press.

Scherer, K.R. (2005). What are emotions? And how can they be measured? Social Science Information, vol. 44 (4), 695-729.

Schwartz, S. H. (1992). Universals in the content and structure of values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. In M. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 25, pp. 1-65). Orlando, FL: Academic Press.

Shweder, R. (1991). Thinking through Cultures: Expeditions in Cultural Psychology. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Shweder, R. A., Much, N. C., Mahapatra, M., & Park, L. (1997). The “big three” of morality (autonomy, community, and divinity), and the “big three” explanations of suffering. In A. Brandt & P. Rozin (Eds.), Morality and health (pp. 119–169). New York, NY: Routledge.

Skevington, S. M., Lotfy, M., & O’Connell, K. A. (2004). The World Health Organization’s WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment: Psychometric properties and results of the international field trial. A Report from the WHOQOL Group. Quality of Life Research, 13, 299–310

Solomon, R. C. (2004). Thinking About Feeling: Contemporary Philosophers on Emotions. Oxford University Press.

Szczurek, L., Monin, B., & Gross, J. J. (2012). The Stranger Effect : The Rejection of Affective Deviants. Psychological Science, 23, 1105-1111.

Totterdell, P. (2000). Catching moods and hitting runs. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85, 848-859.

Townsend, S., Kim, H., & Mesquita, B. (2014). Are you feeling what I’m feeling? Emotional similarity buffers stress. Social Psychology and Personality Science, 5(5), 526-533. doi 10.1177/1948550613511499.

Tsai, J.L. & Clobert, M. (2019). Cultural influences on emotion: Empirical patterns and emerging trends. In S. Kitayama & D. Cohen (Eds). Handbook of Cultural Psychology. Oxford University Press.

[1] I denote discrete emotion terms like ‘anger’ with quotation marks because I consider them to refer to a population of feelings that includes different varieties of feelings characterized by slightly different sets of appraisals and action tendencies, experienced in slightly different types of situations that we still, somehow, came to label by the same word because that is what people in our socio-cultural communities tend to do as well (e.g., Barrett, 2017; Boiger et al., 2018; De Leersnyder, 2019; Parkinson, 2019).

[2] Although acculturation may affect all of us who engage in diverse socio-cultural contexts and thereby engage in sustained first-hand-contact with another culture (see Redfield, Linton & Herskovits, 1936), I mainly study this process in immigrant minorities because it may be most relevant and most detectable among them. Of course, majority members may undergo emotional acculturation as well given enough sustained contact with members from (immigrant) minority groups.