Iris Mauss, Department of Psychology, University of California, Berkeley

Iris Mauss, Department of Psychology, University of California, Berkeley

The research I conduct together with my students and collaborators examines emotions and how people regulate them, often with a focus on how these processes affect people’s psychological health (lab website: https://www.ocf.berkeley.edu/~eerlab/). In particular, we have studied three aspects of emotions: the degree of coherence among different components of emotional responses, people’s ability to regulate emotions once they are “up and running,” and individual and cultural differences in what people believe about emotions.

Emotion Coherence

Emotion theories – and lay intuition – posit that people’s emotional experiences, behaviors, and physiological responses are coordinated during emotional episodes (Ekman, 1992; Levenson, 1994; Panksepp, 1994). For instance, when we feel anxious, we have a strong sense that our heart is racing and our palms are sweaty. Despite the pervasiveness of this emotion coherence hypothesis, empirical support for it is surprisingly limited (Mauss & Robinson, 2009). This intriguing gap led us to develop a new approach to emotion coherence. Rather than examining coherence across individuals (e.g., comparing people who are experiencing different levels of anxiety), we assessed coherence within individuals across time by continuously measuring participants’ emotional experiences, behaviors, and autonomic physiology as they experienced a range of emotions (Mauss, Levenson, McCarter, Wilhelm, & Gross, 2005). When using this approach, these emotion responses were indeed linked. Importantly, however, coherence varied a great deal across individuals, ranging from none to almost perfect coherence.

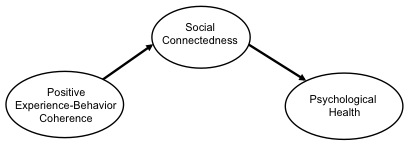

This wide range of individual differences in coherence was a springboard to examine an important question: might emotion coherence serve a function? Take coherence between experience and behavior, for example. Coherence of emotional experiences and behavior may support social processes while dissociation of behavior and experience might disturb them (e.g., someone who smiles without feeling happy might appear inauthentic). The social benefits of experience-behavior coherence, in turn, might contribute to greater psychological health. A longitudinal study confirmed this prediction (Mauss, Shallcross, et al., 2011). People with greater experience-behavior coherence in a laboratory experiment exhibited better psychological health on a follow-up survey two years later. As is illustrated in Figure 1, social connectedness mediated this association, suggesting experience-behavior coherence enhances health because it supports social functioning.

Greater positive experience-behavior coherence predicts greater social connectedness, which predicts greater psychological health

Emotion Regulation

Humans do not just passively experience their emotions. Instead, they actively regulate them, often with the goal of decreasing negative emotion (Gross, Richards, & John, 2006). Our research explores the effectiveness of different emotion regulation strategies. At the center of our research is a paradox: intentionally trying to avoid emotions (“I will stop feeling angry!”) often exacerbates them, perhaps because it directs attention to the very experience it is trying to avoid. How then can people decrease negative emotions?

We have documented three promising emotion-regulation strategies which bypass an intentional focus on decreasing emotion. In the first strategy, people reappraise the situation that precedes their emotional experience so as to experience less negative emotion (Gross, 1998). For example, a person who got into a fight with a friend could reappraise it as a valuable disagreement that will ultimately deepen the friendship. A second route to decreasing negative emotion is not to control it but rather to accept it, as is the case when one embraces one’s sadness over a loss as a normal response (Hayes, Wilson, Gifford, Follette, & Strosahl, 1996; Segal, Williams, & Teasdale, 2002; Shallcross, Ford, Floerke, & Mauss, 2013) Paradoxically, acceptance may allow people to pay less attention to the negative emotion, and therefore feel it less. While reappraisal and acceptance have quite different proximal goals (reappraisal is aimed at changing how one thinks about the emotional situation while acceptance is aimed at accepting one’s emotional responses) both have the same outcome: decreased experience of negative emotion. Finally, automatic emotion regulation avoids intention altogether by associating certain situations unconsciously with emotion-regulation goals (Mauss, Bunge, & Gross, 2007). For example, in cultures that discourage anger in social situations, people may over time automatically associate social situations with the goal of decreasing anger.

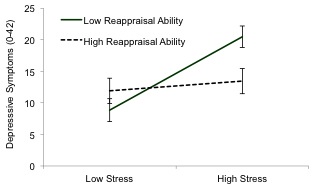

For each of these strategies, we have documented with laboratory experiments and correlational studies that they effectively decrease negative emotions and increase psychological health (Hopp, Troy, & Mauss, 2011; Mauss, Cook, Cheng, & Gross, 2007; Mauss, Cook, & Gross, 2007; Shallcross, Troy, Boland, & Mauss, 2010). For example, we measured reappraisal ability by assessing how much participants could use reappraisal to modulate their experiential and physiological responses to sad films. We then showed that reappraisal ability predicted psychological health in people who had recently experienced stressful life events (e.g., a divorce). As depicted in Figure 2, among participants with low reappraisal ability, stress severity was related to depressive symptoms; but among participants with high reappraisal ability, depressive symptoms were low and not related to stress severity (Troy, Wilhelm, Shallcross, & Mauss, 2010).

Depressive symptoms as a function of stress severity and reappraisal ability. Reappraisal ability protects participants from the harmful effects of stress on depression

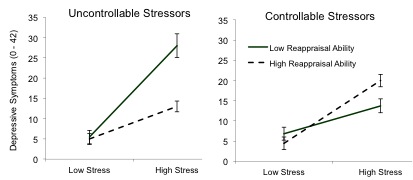

More recently, we have begun to look beyond the individual in explaining links between emotion regulation and health outcomes. Our thinking is that few individual-level factors have invariant effects. Rather, the usefulness of individual-level factors usually depends on their context. For instance, when stressors are controllable, regulating one’s own emotions instead of changing one’s situation may be counterproductive (Troy, Shallcross, & Mauss, in press). In support of this idea, we found that reappraisal ability protected stressed participants from depression – but only when stress was uncontrollable (e.g., a family member’s death). When stress was more controllable (e.g., a conflict at work), greater reappraisal ability was associated with more depression (Figure 3).

Depressive symptoms as a function of stress severity, stress controllability, and reappraisal ability. Reappraisal ability is protective in the context of relatively uncontrollable stressors but harmful in the context of relatively controllable stressors

Beliefs about Emotion

Our third line of work explores how people’s beliefs about emotions affect their emotions, emotion regulation, and health (Mauss & Tamir, in press). We focus on two sets of beliefs: 1) beliefs regarding whether emotions should be controlled, or, emotion control values; and 2) beliefs regarding which emotions one should experience, or, valued emotions.

A potent source of emotion control values is culture (Markus & Kitayama, 1991; Tsai, Knutson, & Fung, 2006). In a laboratory study, for instance, we found that Asian Americans value emotion control more than do European Americans, and, accordingly, experience less anger than European Americans in response to an anger provocation (Mauss, Butler, Roberts, & Chu, 2010). A second study documented the power of these cultural values to impact health-relevant processes. Reflecting that Asian Americans, relative to European Americans, value emotion control more, emotion control values were linked to an adaptive pattern of cardiovascular challenge for Asian-American participants. In contrast, for European-American participants, emotion control values were associated with a maladaptive pattern of cardiovascular threat (Mauss & Butler, 2010).

The pursuit of happiness can backfire, or, as Nathaniel Hawthorne wrote, “Happiness is like a butterfly which, when pursued, is always beyond our grasp, but, if you will sit down quietly, may alight upon you”

Beliefs about which emotions one should experience also influence health. We have focused on happiness as an emotion that people have particularly strong beliefs about (Ford & Mauss, in press; Gruber, Mauss, & Tamir, 2011). Combining evidence from experimental and individual-difference approaches, we find that – paradoxically – the more people value happiness the more unhappy and at risk for depression they are (Mauss, Tamir, Anderson, & Savino, 2011). These effects appear to be due to people being more likely to be disappointed when they believe they should feel very happy. Broadly, these findings show that how people think about emotions – their emotion beliefs and values – plays a profound role in the experience and regulation of emotion.

Concluding Comment

Affective science is a relatively new research area. Yet for centuries, philosophers and scientists have debated questions such as: What is an emotion? What functions do emotions serve? Should people control their emotions, and if so, how can they do so? How are emotions and their regulation involved in health, disease, and the ‘good life’? Our research speaks to these questions by examining emotion coherence, emotion regulation, and people’s values and beliefs about emotion. In exploring these questions, we hope to contribute to a better understanding of emotions, their regulation, and their implications for health.

To know more about Iris, check out the video below, which is part of the very interesting Experts in Emotion Series directed by June Gruber at Yale University.

References

Ekman, P. (1992). An argument for basic emotions. Cognition & Emotion, 6, 169-200.

Ford, B. Q., & Mauss, I. B. (in press). The paradoxical effects of pursuing positive emotion: When and why wanting to feel happy backfires. In J. G. J. Moskowitz (Ed.), Positive emotion: Integrating the light and dark sides. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gross, J. J. (1998). Antecedent- and response-focused emotion regulation: Divergent consequences for experience, expression, and physiology. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 224-237.

Gross, J. J., Richards, J. M., & John, O. P. (2006). Emotion regulation in everyday life. In D. K. Snyder, J. Simpson & J. N. Hughes (Eds.), Emotion regulation in couples and families: Pathways to dysfunction and health (pp. 13-35). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Gruber, J., Mauss, I. B., & Tamir, M. (2011). A dark side of happiness? How, when, and why happiness is not always good. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6, 222–233.

Hayes, S. C., Wilson, K. G., Gifford, E. V., Follette, V. M., & Strosahl, K. (1996). Experiential avoidance and behavioral disorders: A functional dimensional approach to diagnosis and treatment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 64, 1152-1168.

Hopp, H., Troy, A. S., & Mauss, I. B. (2011). The unconscious pursuit of emotion regulation: Implications for psychological health. Cognition and Emotion, 25, 532-545. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2010.532606

Levenson, R. W. (1994). Human emotion: A functional view. In P. Ekman & R. J. Davidson (Eds.), The nature of emotion: Fundamental questions (pp. 123-126). New York: Oxford University Press.

Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review, 98, 224-253.

Mauss, I. B., Bunge, S. A., & Gross, J. J. (2007). Automatic emotion regulation. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 1, 146-167. doi: 0.1111/j.1751-9004.2007.00005.x

Mauss, I. B., & Butler, E. A. (2010). Cultural context moderates the relationship between emotion control values and cardiovascular challenge versus threat responses. Biological Psychology, 84, 521–530.

Mauss, I. B., Butler, E. A., Roberts, N. A., & Chu, A. (2010). Emotion control values and responding to an anger provocation in Asian-American and European-American individuals. Cognition and Emotion, 24, 10261043.

Mauss, I. B., Cook, C. L., Cheng, J. Y. J., & Gross, J. J. (2007). Individual differences in cognitive reappraisal: Experiential and physiological responses to an anger provocation. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 66, 116-124.

Mauss, I. B., Cook, C. L., & Gross, J. J. (2007). Automatic emotion regulation during anger provocation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 43, 698-711. doi: 10.1016/J.Jesp.2006.07.003

Mauss, I. B., Levenson, R. W., McCarter, L., Wilhelm, F. H., & Gross, J. J. (2005). The tie that binds? Coherence among emotion experience, behavior, and physiology. Emotion, 5, 175-190.

Mauss, I. B., & Robinson, M. D. (2009). Measures of emotion: A review. Cognition and Emotion, 23, 209-237.

Mauss, I. B., Shallcross, A. J., Troy, A. S., John, O. P., Ferrer, E., Wilhelm, F. H., & Gross, J. J. (2011). Don’t hide your happiness! Positive emotion dissociation, social connectedness, and psychological functioning. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 100, 738-748. doi: 10.1037/a0022410

Mauss, I. B., Tamir, M., Anderson, C. L., & Savino, N. S. (2011). Can seeking happiness make people unhappy? Paradoxical effects of valuing happiness. Emotion, 11, 807-815. doi: 10.1037/a0022010

Panksepp, J. (1994). The basics of basic emotions. In P. E. R. J. Davidson (Ed.), The nature of emotion: Fundamental questions (pp. 237-242). New York: Oxford University Press.

Segal, Z. V., Williams, J. M. G., & Teasdale, J. D. (2002). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression: A new approach to preventing relapse. New York, NY, US: Guilford Press.

Shallcross, A. J., Ford, B. Q., Floerke, V. A., & Mauss, I. B. (2013). Getting better with age: The relationship between age, acceptance, and negative affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 734-749.

Shallcross, A. J., Troy, A. S., Boland, M., & Mauss, I. B. (2010). Let it be: Accepting negative emotional experiences predicts decreased negative affect and depressive symptoms. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 48, 921-929. PMCID: PMC3045747.

Troy, A. S., Shallcross, A. J., & Mauss, I. B. (in press). A person-by-situation approach to emotion regulation: Cognitive reappraisal can either hurt or help, depending on the context. Psychological Science.

Troy, A. S., Wilhelm, F. H., Shallcross, A. J., & Mauss, I. B. (2010). Seeing the silver lining: Cognitive reappraisal ability moderates the relationship between stress and depression. Emotion, 10, 783-795. doi: 10.1037/a0020262

Tsai, J. L., Knutson, B., & Fung, H. H. (2006). Cultural variation in affect valuation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90, 288-307. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.90.2.288