Department of Philosophy, Bryn Mawr College

In recent years, angry protest and activism has been on the rise. From #BlackLivesMatter to #meToo, social movements have harnessed and expressed the anger of those who feel wronged, oppressed, left behind, and ignored. This rise in angry social protest seems to reflect growing feelings of anger more generally. According to the 2019 Gallup Global Emotions Report, Americans’ anger increased significantly in 2018, and 20% of US respondents reported that they felt anger “a lot.” Younger Americans were more likely to feel angry with 32% of 15-29-year-olds reporting that they feel a great deal of anger. And it isn’t just people in the United States who are angry. In some parts of the world, such as Armenia, Iran and Palestine, over 40% of the population reported that they “experienced anger a lot yesterday.”

What should ethicists and social philosophers think about all this anger? Is it a lamentable moral and political failure or something that we should admire? Philosophers have taken a variety of positions on anger’s value and disvalue, and while I cannot do justice to this literature here, I aim to sketch out a few features of the dominant views regarding the moral and political status of anger before going on to highlight what I see as two preconditions on morally apt anger.

Ethicists have long worried that anger can undermine good judgment and moral sense. The Stoic philosopher Seneca is particularly harsh in his assessment of the ways in which anger functions as a barrier to judgment, describing anger as a “departure from sanity.” He writes: “Unlike other failings, anger does not disturb the mind so much as take it by force; harrying it on out of control and eager even for universal disaster, it rages not just as its objects but at anything it meets on its way.” (Seneca, 1995, p.77) According to this characterization, anger is indiscriminate and cannot maintain its focus on its purported target and has calamitous consequences. Within contemporary philosophy, it is commonly argued that anger and other hard feelings inevitably drive away allies and lead to bad social outcomes. Glen Pettigrove (2012), for example, has argued that anger undermines friendships, compromises social utility, makes it difficult to coordinate our actions successfully with others, and clouds our judgment. Martha Nussbaum (2016) has offered similar arguments against anger and has claimed that we ought to instead strive for an attitude of civic love. While their positions are nuanced, we can refer to these philosophers as the “anger pessimists”; they are generally critical of anger and its effects.

Surely anger pessimists are at least partially right in their assessments: anger can have serious negative consequences and experiencing anger may, in some circumstances, be objectionable and count as a significant moral failing. But others have insisted that anger has overriding moral and political value that the anger pessimists fail to fully acknowledge. These philosophers aren’t necessarily optimistic in their assessments regarding anger, but they do offer various defenses of it, and I will describe this motley group as “anger defenders.” But before turning to what has been said in defense of anger, we should get a bit clearer on the nature of anger.

To individuate anger from neighboring emotions, we need to consider how anger presents the world to its subject. In other words, we need an account of what has been termed anger’s evaluative presentation (D’Arms and Jacobson, 2000).

Aristotle defined anger as follows:

Aristotle defined anger as follows:

Anger may be defined as a desire accompanied by pain, for a conspicuous revenge for a conspicuous slight at the hands of men who have no call to slight oneself or one’s friends. If this is a proper definition of anger, it must always be felt toward some particular individual, e.g., Cleon, and not man in general. It must be felt because the other has done on intended to do something to him or one of his friends. It must always be attended by a certain pleasure—that which arises from the expectation of revenge. For it is pleasant to think that you will attain what you aim at, and nobody aims at what he thinks he cannot attain (1984b, 1378a-1378b)

For Aristotle, anger necessarily involves the desire for revenge, and it is easy to see why some might insist that if anger always involves this desire for revenge, anger is always morally ugly and prudentially counter-productive (Nussbaum, 2016). However, it is not obvious that anger should be identified with this desire (Callard, 2017), and even if anger did always involve a desire for revenge, a case could be made that this desire for revenge is morally innocuous and not socially imprudent in every case. A desire for revenge could be characterized as a desire to see that the target suffer some form of physical injury as a form of payback for the perceived slight, and this desire may well be morally objectionable for it isn’t clear what moral damage slights do in the first place, and more fundamentally, it isn’t clear how physical violence could ever ameliorate or right this moral damage. But a desire for revenge could be understood simply as the desire that the target suffer psychologically, and it isn’t obvious that this desire is morally abhorrent. For if the target has done something wrong and recognizes that they have done wrong, they will suffer, psychologically, if not physically. Feeling guilt or remorse is a psychologically painful form of suffering, and there doesn’t seem to be anything morally objectionable about desiring that the person who has done you wrong come to recognize this and suffer psychologically as a result. Moreover, if this is all the desire for revenge amounts to, it is difficult to see what would be socially imprudent about it.

Whatever we ultimately conclude about the moral status of the desire for revenge, at the most basic level, to be angry is to see oneself as wronged or thwarted in some personally significant way, and anger is a hostile emotion that is a response this perceived interference. The angry person will also undergo various physiological changes and may be more disposed toward some actions rather than others, but this general characterization of anger’s evaluative presentation allows us to distinguish it from neighboring negative emotions. In what follows, I will be focusing on the kind of anger that experienced when one takes oneself to have been wronged by another. Philosophers sometimes refer to this subspecies of anger as resentment. I will use the term anger in what follows, but I have in mind anger that is a response to a perceived wrongdoing.

Like all emotions, anger can be assessed as “appropriate” along several dimensions: we can evaluate a token of anger in terms of its prudence, moral value, aesthetic value, reasonableness, and so on. We may describe an emotion that is all-in appropriate as “apt.”

For our purposes, fittingness is an especially important mode of affective evaluation: if an emotion is fitting, then its evaluative presentation is accurate, i.e., it correctly presents the world. To resent a paperclip is to see the paperclip as having wronged you; your resentment in this case would be unfitting because paperclips are not the sorts of entities that can actually do wrong. When one recognizes that one’s emotion is unfitting, one has reasons to overcome it.

Contemporary defenders of anger don’t usually defend it as a good way of responding to slights; instead, it is argued that anger can be a fitting and morally good response to wrongdoing and oppression. For example, according to Jeffrie Murphy (1988, p.17), resentment is a way of asserting our self-respect; when we fail to resent appropriately, we express “emotionally—either that we do not think that we have rights or that we do not take our rights very seriously.”

Aristotle states that an excellent person will feel anger when it is called for; a person who does not respond to significant slights with anger can be criticized as “slavish” and a person who responds with excessive anger or is too quick to anger may be criticized as “irascible”:

The person who is angry at the right things and toward the right people, and also in the right way, at the right time, and for the right length of time, is praised. This, then, will be the mild person, if mildness is praised. For being a mild person means being undisturbed, not led by feeling, but irritated wherever reason prescribes, and for the length of time it prescribes. And he seems to err more in the direction of deficiency, since the mild person is ready to pardon, not eager to exact a penalty. (1984a, 1125b-1126a)

Aristotle contrasts this mild person, whose reason directs him to respond with anger only to those slights which are worth getting angry about, with the person who is deficient in anger, and claims that the latter is open to criticism:

For people who are not angered by the right things, or in the right way, or at the right times, or toward the right people, all seem to be foolish. For such a person seems to be insensible and to feel no pain, and since he is not angered, he does not seem to be the sort to defend himself. Such a willingness to accept insults to oneself and to overlook insults to one’s family and friends is slavish. (1984a, 1126a)

The irascible person goes wrong in a different way. Such a person gets angry at the wrong person, at the wrong time, and so on. Moreover, this person does not “….contain their anger, but their quick temper makes then pay back the offense without concealment, and then they stop.” (1984a, 1126a)

For Aristotle, a virtuous person will feel the sting of slights and will respond to significant slights with anger as a way of taking himself seriously and defending his honor. He isn’t quick to lash out in anger; the motivational dispositions associated with anger are dispositions, and they can come apart from the anger experience.

For Aristotle, a virtuous person will feel the sting of slights and will respond to significant slights with anger as a way of taking himself seriously and defending his honor. He isn’t quick to lash out in anger; the motivational dispositions associated with anger are dispositions, and they can come apart from the anger experience.

Aristotle ties the value of anger to its role in registering and protesting slights. Although contemporary philosophers may reject many aspects of Aristotle’s worldview, there is a significant literature in feminist philosophy arguing that anger is valuable as a defensive emotion under circumstances of oppression (philosophers have also explored the role that anger, and more specifically resentment, plays in holding persons responsible [Strawson, 1962] and the role it plays in punishment [Bennett, 2002]). While anger has been defended on a number of grounds, there are four general defenses of anger in this literature. (Bell, 2009)

First, anger is defended as a mode of protesting wrongs done and oppressive structures. According to this line of argument, angry protest registers wrongs as wrong and helps subjects maintain their self-respect under conditions of oppression. To forgo anger when it is merited might be to acquiesce or condone the wrong done.

Second, anger is thought to be valuable insofar as it provides knowledge about the world. Those who stress what we can call the direct epistemic value of anger claim that those who experience anger have knowledge that the non-angry lack. For example, Uma Narayan (1988) argues that the oppressed have a kind of epistemic privilege; one aspect of this privilege is the knowledge “constituted and confirmed by the emotional responses of the oppressed to their oppression.”(p.39) Those who stress the indirect epistemic value of anger argue that people can learn a great deal about their status in society by looking at how their anger is received by others. Marilyn Frye (1983), for example, has argued that women’s anger is given uptake (i.e., taken seriously as anger) in areas where women are seen as having authority, such as being a mother or nurturer. As Frye puts it, “anger can be an instrument of cartography” though which women can map out others’ conceptions of their status.

Third, some have argued that anger is important insofar as it is a way of disvaluing the disvaluable. Even in cases where protest would be impossible or ineffective, it has been argued that anger is still morally valuable insofar as it is fitting and bears witness to injustice.

Fourth, some have argued that anger is valuable insofar as it motivates social change. Audre Lorde (1984) writes: “anger between peers births change, not destruction, and the discomfort and sense of loss it often causes is not fatal, but a sign of growth. My response to racism is anger.” As Lorde sees it, anger can be morally valuable insofar as it helps to bring about a good end, such as social change.

To sum up, anger’s defenders have argued that anger is a mode of protest that can help secure persons’ self-respect, that anger has at least two distinct epistemic roles, that it is a mode of disvaluing the disvaluable, and that it can directly motivate social change. Under circumstances of injustice, there will constantly be occasions for anger, and therefore fitting anger may be unhealthy for its subject (Tessman, 2005), but this does not necessarily tell against its aptness (Srinivasan, 2018 and McFall, 1991).

In what follows, I’d like to consider what preconditions need to be met for anger to play these roles. As I see it, anger is morally and politically valuable only if it is regarded as a way of asserting a claim. For anger to be regarded as making a claim, two conditions need to be met. First, the anger shouldn’t be utterly dismissed by the target or third parties. Second, subjects should be open to assessing the claims being made through it. If we don’t think of anger as a way of making claims, it is difficult to see how it can have the value that anger defenders suggest.

While a number of philosophers have argued that we should take the “outlaw” emotions of the marginalized especially seriously because the subordinated are “epistemologically privileged” and are therefore more likely to experience fitting emotions regarding their oppression, we shouldn’t misconstrue this claim: While some want to question how we mark the distinction between fitting and unfitting emotions (MacLachlan, 2010) and others question whether bias will infect our anger assessments (Cherry, 2018), it clearly isn’t the case that the emotions of the subordinated are always fitting. Alison Jaggar, who defends the epistemic value of outlaw emotions, stresses that the anger of the oppressed can be unfitting and inapt, just as the anger of the non-oppressed can be, and often is, unfitting and inapt: “Like all our faculties, [emotions] may be misleading, and their data, like all data, are always subject to reinterpretation and revision…they are open to challenge on various grounds. They may be dishonest or self-deceptive, they may incorporate inaccurate or partial perceptions, or they may be constituted by oppressive values. Accepting the indispensability of appropriate emotions to knowledge means no more (and no less) than that discordant emotions should be attended to seriously and respectfully rather than condemned, ignored, discounted, or suppressed.” (1989, p.169)

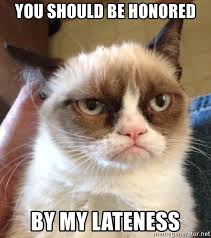

In order to determine whether some token of anger is fitting, we need to consider, in detail, the subject’s anger, her perceived reasons for her anger, the target’s actions, and the relationship between the subject and target. Making these sorts of assessments is something that we do, and in some cases only can do, by engaging in certain familiar forms of dialogue. Giving an account or justification of our emotions is an important social practice through which people attempt to come to a shared understanding of the fittingness conditions for emotions. To illustrate the kind of process I have in mind, consider a prosaic example: I saunter up to you waiting for me outside the cafe, and you say, “God, I can’t believe you! I’m so sick of this!” and I immediately ask, “What’s wrong? Why are you mad? What did I do?” In asking why you are angry, I am not asking for a causal story of what brought you to this state. Instead, I am asking you for a justificationfor the way you are currently appraising the world; I’m asking you for a justification for your anger. You say, “because you were late! And I’ve just been sitting here wasting my time!” At this point in our exchange I have a number of options: I may accept that my tardiness justifies your anger and apologize, or I may offer an explanation that excuses my lateness, or I may admit that I was late but question whether I wronged you in arriving late—perhaps we have a tacit agreement that we allow one another a 20 minute grace period, and so on. It is through ordinary exchanges like this that we come to both set and know the fittingness conditions for our emotions. These ordinary exchanges are corrupted in cases of affective dismissal. (Bell, 2019)

In order to determine whether some token of anger is fitting, we need to consider, in detail, the subject’s anger, her perceived reasons for her anger, the target’s actions, and the relationship between the subject and target. Making these sorts of assessments is something that we do, and in some cases only can do, by engaging in certain familiar forms of dialogue. Giving an account or justification of our emotions is an important social practice through which people attempt to come to a shared understanding of the fittingness conditions for emotions. To illustrate the kind of process I have in mind, consider a prosaic example: I saunter up to you waiting for me outside the cafe, and you say, “God, I can’t believe you! I’m so sick of this!” and I immediately ask, “What’s wrong? Why are you mad? What did I do?” In asking why you are angry, I am not asking for a causal story of what brought you to this state. Instead, I am asking you for a justificationfor the way you are currently appraising the world; I’m asking you for a justification for your anger. You say, “because you were late! And I’ve just been sitting here wasting my time!” At this point in our exchange I have a number of options: I may accept that my tardiness justifies your anger and apologize, or I may offer an explanation that excuses my lateness, or I may admit that I was late but question whether I wronged you in arriving late—perhaps we have a tacit agreement that we allow one another a 20 minute grace period, and so on. It is through ordinary exchanges like this that we come to both set and know the fittingness conditions for our emotions. These ordinary exchanges are corrupted in cases of affective dismissal. (Bell, 2019)

To give some emotion uptake is not necessarily to capitulate to it or express one’s agreement with its content. I can give your anger uptake even while being skeptical of its fittingness. When an irate student barges in and demands that he be given an A rather than a B+ on his midterm exam, I can tell him that his anger is misplaced and that his exam doesn’t merit the higher grade without being dismissive of his anger. I can take the student’s anger seriously as anger even as I dispute its fittingness. But when a person’s anger is utterly dismissed, on the other hand, its content is ignored and its claim is not acknowledged as a claim (Frye, 1983 and Campbell, 1994). When your interlocutor responds to your anger by asking if you are done or with a joke about PMS, then your anger is not being given uptake. The fittingness of your anger isn’t being challenged; instead, the claim inherent in your anger, the claim that you have been wronged, is not taken seriously. In fact, it is not treated as a claim at all. In order for anger to do the moral and political work that anger defenders describe, affective dismissal must not be widespread.

Subjects can also fail to treat their anger as a vehicle for making claims if they refuse to be open to the type of dialogic process described above. If a subject will not offer reasons for her anger or is unwilling to consider the views of those who see her anger as unfitting, she is not treating her anger as a way of making a claim. If subjects do not treat their anger as claims, then the anger cannot do the type of ameliorative work that anger defenders describe.

I have not attempted fully adjudicate the debate between the anger pessimists and the anger defenders here. No matter what one’s position on the moral and political value and disvalue of anger, all should agree that there are better and worse ways of experiencing anger, and the philosophical literature on the moral psychology of anger can help us understand the pitfalls and promise of this all too common emotion.

References

Aristotle (1984a). Nicomachean Ethics.In J. Barnes (Ed.), The Complete Works of Aristotle: The Revised Oxford Translation. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Aristotle (1984b).Rhetoric. In J. Barnes (Ed.), The Complete Works of Aristotle: The Revised Oxford Translation. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Bell, M. (2009). Anger, Virtue, and Oppression. In L. Tessman (Ed.), Feminist Ethics and Social and Political Philosophy: Theorizing the Non-Ideal(pp. 165-183). New York, NY: Springer.

Bell, M. (2009). The wrong of affective dismissal. Unpublished manuscript.

Bennett, C. (2002). The varieties of retributive experience. The Philosophical Quarterly, 52, 145-163.

Callard, A. (2018). The Reason to be Angry Forever. In M. Cherry & O. Flanagan (Eds.), The Moral Psychology of Anger(pp.123-137). London: Rowman & Littlefield.

Campbell, S. (1994). Being dismissed: On the politics of emotional expression. Hypatia, 9, 46-65.

Cherry, M. (2018). The errors and limitations of our ‘anger-evaluating’ ways. In M. Cherry & O. Flanagan, The Moral Psychology of Anger(pp. 49-65). London: Rowman & Littlefield.

D’Arms, J., & Jacobson, D. (2000). The moralistic fallacy: On the ‘appropriateness’ of emotions. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 61, 65-90.

Frye, M. (1983). The Politics of Reality: Essays in Feminist Theory. Berkeley, CA: Crossing Press

Jaggar, A. (1989). Love and knowledge: Emotion in feminist epistemology. Inquiry, 32, 151-176.

Lorde, A. (1984). The uses of anger: Women responding to racism. Sister Outsider, 127, 131.

MacLachlan, A. 2010. Unreasonable resentments. Journal of Social Philosophy, 41, 422-441.

McFall, L. (1997). What’s wrong with bitterness? In C. Card (Ed.), Feminist Ethics.Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas.

Murphy, J. G., & Hampton, J. (1988). Forgiveness and Mercy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Nussbaum, M. (2016). Anger and Forgiveness. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Narayan, U. (1988). Working together across difference: Some considerations on emotions and political practice. Hypatia, 3, 31-48.

Pettigrove, G. (2012). Meekness and ‘moral’ anger. Ethics, 122, 341-370.

Seneca (1995). On Anger. In J. Cooper & J. F. Procone (Eds.), Seneca: Moral and Political Essays. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Srinivasan, A. (2018). The aptness of anger. Journal of Political Philosophy, 26, 123-144.

Strawson, P. F. (1962). Freedom and Resentment. Proceedings of the British Academy,48, 1-25.

Tessman, L. (2005). Burdened Virtues: Virtue Ethics for Liberatory Struggles. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.