Joshua Tybur, Dept of Social and Organizational Psychology, VU University Amsterdam & Debra Lieberman, Dept of Psychology, University of Miami

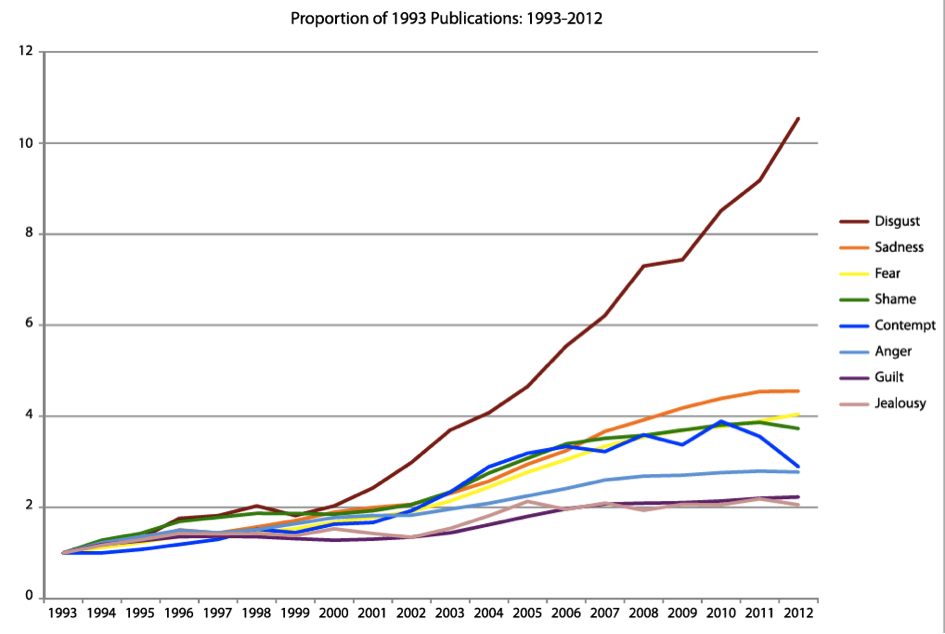

While disgust as a subject of inquiry has skyrocketed in popularity over the past 20 years (see Figure 1), there has yet to be a consensus among psychologists regarding disgust’s function(s). We believe this is partially due to the variation in objects, concepts, and behaviors that elicit disgust—things as varied as lawyers, vomit, incest, diapers, politicians, and sex during menstruation (e.g., Curtis & Biran, 2001; Haidt et al., 1997; Nabi, 2002).

While disgust as a subject of inquiry has skyrocketed in popularity over the past 20 years (see Figure 1), there has yet to be a consensus among psychologists regarding disgust’s function(s). We believe this is partially due to the variation in objects, concepts, and behaviors that elicit disgust—things as varied as lawyers, vomit, incest, diapers, politicians, and sex during menstruation (e.g., Curtis & Biran, 2001; Haidt et al., 1997; Nabi, 2002).

Although some have suggested that disgust is best described as having the generic function of “protecting the self” (e.g., Miller, 2004), others have proposed that the heterogeneity of disgust elicitors reflects multiple disgust adaptations, each of which evolved in response to distinct selection pressures. For example, Rozin, Haidt, McCauley and colleagues (RHM; 2008, 2009) suggest disgust evolved from distaste—a food-rejection adaptation for neutralizing toxins—in response to new selection pressures imposed by pathogens in the varied, omnivorous human diet.

Inspired by cultural anthropologist Ernest Becker (1973), RHM further argue that this pathogen-avoidance emotion was exapted for a new function: to “protect the soul” (Rozin et al., 2008, p. 764) by neutralizing purported existential threats posed by reminders that humans are animals and, hence, mortal. Rozin et al. (2008) argue that this perspective is supported by their observation that “anything that reminds us that we are animals elicits disgust.” (p. 761).

Prototypical animal reminders, under this framework, include dead bodies, deformity (e.g., burn wounds, port wine birthmarks), bad hygiene (e.g., body odor), and sex. RHM also posit domains of “interpersonal” disgust, which they argue functions to maintain social distinctiveness, and moral disgust, which they argue functions to protect the social order. We do not further address moral disgust here (though see Tybur, Lieberman, Kurzban, and DeScioli, 2013, pages 73-77, for our account of morality and “purity” and “divinity” violations, as well as disgust toward unfair and harmful acts). Briefly, then, RHM posit four functions for disgust: 1) to neutralize pathogens; 2) to neutralize the purported threats posed by reminders that humans are animals; 3) to maintain social distinctiveness, and 4) to protect the social order.

In contrast to the type of evolutionary trajectory proposed by RHM, we, along with other researchers in the area, (e.g., Curtis et al., 2011; Fessler & Navarrete, 2003) have suggested that disgust evolved to perform a different set of functions. Specifically, we have argued that disgust functions in the realms of pathogen avoidance, sexual choice, and moral judgment (see Tybur, Lieberman, & Griskevicius, 2009; Tybur et al., 2013). Here, we will refer to this as the three domain disgust (3DD) model. The 3DD and RHM models are similar in that they both posit evolved functions for disgust, and both posit that disgust serves some pathogen-avoidance function. They differ in a number of ways as well. For example, the 3DD model does not argue that disgust evolved from distaste to neutralize food borne pathogens, but that it evolved from pathogen avoidance adaptations that are ubiquitous across species. Further, the 3DD model includes functions relevant to sexual choice, whereas the RHM model does not; similarly, the RHM model includes functions relevant to symbolically protecting the soul, whereas the 3DD model does not. These differences are fleshed out to make different predictions below. First, we provide further details regarding the 3DD model.

Conspecifics and animals are potential sources of pathogens. All else equal, psychological mechanisms that detected pathogens and motivated physical avoidance of them would have conferred reproductive advantages. Note that these do not need to be food borne pathogens. Indeed, touching vomit, feces, and other sources of pathogens with the hands can cause infection even if the pathogen sources are not directly ingested. For example, pathogens on the hands can enter the body via cuts and scrapes, and they can be transmitted to otherwise noninfectious foods, which can then be consumed. In contrast to the animal-reminder function proposed by RHM, we suggest that disgust toward corpses, deformity, and bad hygiene functions to reduce physical contact based on the pathogen-relevant information associated with these objects. We further suggest that disgust toward sex, rather than functioning to neutralize reminders that humans are animals, evolved to motivate avoidance of specifically sexual (rather than generally physical) contact with individuals who impose net reproductive costs as sexual partners. Mating with close genetic relatives, for instance, imposes significant reproductive costs, and evolution should have engineered psychological mechanisms to prevent and deter sexual, but not physical, contact. Sexual disgust, we argue, was exapted from pathogen disgust and modified (e.g., to motivate avoidance of sexual contact rather than purely physical contact) to perform this function.

These two evolutionary models propose different functional explanations for disgust toward items that RHM state fall into an “animal-reminder” category. On the one hand, RHM suggest disgust toward dead bodies, bad hygiene, body products, and sex functions to neutralize the existential threats posed by reminders that we are animals and thus mortal. On the other hand, the 3DD model suggests two different adaptations underlie disgust toward corpses and sex: one for avoiding physical contact with pathogens and another for avoiding sexual contact with reproductively costly mates. We feel that the best way to evaluate these models is to use them to generate competing, testable predictions and compare the extent to which each model is supported by observations. Here we consider predictions regarding contact with corpses and disgust toward sex.

Let’s first consider disgust toward corpses and the predictions each model makes regarding (a) the consequences of failing to avoid physical contact with corpses (i.e., what happens if disgust were somehow removed, but physical contact, direct or indirect, remains), and (b) whether non-human animals avoid corpses. With respect to (a), the 3DD model predicts that failing to avoid physical contact with corpses increases infectious disease costs, whereas the animal-reminder perspective does not make this prediction (recall, the RHM model posits that the key threats posed by corpses are symbolic and existential, not infectious). With respect to (b), the animal-reminder perspective predicts that only humans – so not non-human animals – should avoid corpses, since (purportedly) only humans can forecast their own mortality. In contrast, the 3DD model predicts that many species should avoid corpses, since the threats posed by decaying conspecifics (e.g., infectious disease) are not unique to humans.

In both cases, the pathogen-avoidance perspective as outlined by the 3DD model fits observations better. As Ignaz Semmelweis discovered, removing the cues associated with putrefying bodies—and, hence, removing the disgust that motivates physical avoidance—can lead to inadvertent pathogen transmission and lethal infections. And, as multiple animal-behavior researchers have shown, non-human animals avoid dead conspecifics, partially to avoid infection from pathogens that might have killed the animal or that are rapidly colonizing the corpse (indeed, “reminding” non-human animal pests of dead conspecifics via olfactory cues is used to manage pests; see Wagner et al., 2011).

Using sex as another example, we can also consider the competing predictions each model makes regarding (a) how imagining sex with different partners changes disgust toward sexual acts, and (b) differences between men and women in disgust toward sex. Regarding (a), the animal-reminder perspective suggests that the act of sexual intercourse should elicit disgust, because non-human animals also have intercourse–there is no distinction based on sexual partner implied by this model. In contrast, the 3DD model suggests that a sexual act should elicit disgust if the partner is perceived to be reproductively costly, but not if the partner is perceived to be reproductively beneficial. In our view, the animal-reminder perspective, again, does not fare well. For example, a 25 year-old man would likely find sexual intercourse with his 22 year-old sister disgusting, even if the sister possesses physical and mental traits he otherwise finds attractive (see, e.g., De Smet, Speybroeck, & Verplaetse, in press; Lieberman, Tooby, and Cosmides, 2007). But the same “animalistic” act of intercourse with an unrelated, but equally attractive 22 year-old woman elicits lust rather than disgust.

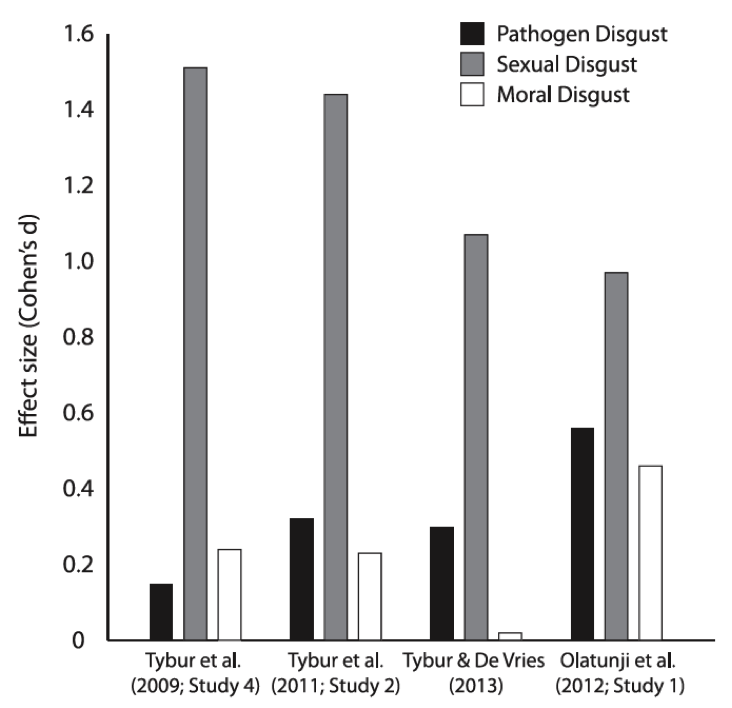

Data describe standardized mean sex differences (the difference between women’s scale scores and men’s scale scores in standard deviation units, or Cohen’s d) in Three Domain Disgust Scale (TDDS) factor means across four data sets. The TDDS is a 21-item measure in which participants self-report, on a 0 = not at all disgusting to 6 = extremely disgusting scale, how disgusting they find statements. Some statements concern pathogen cues (e.g., “Stepping on dog poop”), some concern sexual situations (e.g., “Finding out that someone you don’t like has sexual fantasies about you”), and some concern moral violations (e.g., “A student cheating to get good grades”). Factor means are averages across the seven items per factor. Women’s mean scores are higher across every data set and every TDDS factor.

With respect to (b), the RHM model would predict that men and women should be roughly equally disgusted by sex. In contrast, based on Parental Investment Theory, (Trivers, 1972), which states that the sex that invests more in reproduction (e.g., via time and metabolic resources) should be sexually choosier, the 3DD model predicts that women should be more avoidant of – and hence more disgusted by – sex than men (Tybur et al., 2013). Data support the 3DD model, with multiple studies finding that women are much more sensitive to sexual disgust than men. That is, when asked to self-report how disgusted they are by a variety of disgust elicitors, women report far greater disgust toward sexual items than men do. Indeed, the magnitude of these sex difference dwarfs the magnitude of sex difference in disgust toward other elicitors grouped within the “animal-reminder” domain by RHM and disgust toward moral violations (see Figure 2).

This – along with other data (see Tybur et al., 2009, Study 4) suggests that disgust toward sex and disgust toward corpses should not be categorized into the same “domain,” and that the threats that sexual disgust functions to neutralize vary across men and women.

We believe that the recent surge in disgust research can have maximum impact if guided and interpreted using a robust theoretical framework. Given the current theoretical and empirical arguments against the existence of an “animal–reminder” function of disgust as outlined by RHM (see Al-Shawaf and Lewis, 2013; Royzman and Sabini, 2001, Tybur et al., 2009, 2013), we believe that it is time to retire this candidate functional explanation.

Moving forward, we suggest that researchers continue to explore topics such as the proximate (i.e., information processing) mechanisms underlying plausible evolved functions, discussing the degree to which disgust functions to promote group versus individual fitness (see Pinker, 2012, for a discussion), and discussing the role of cultural evolution in the structure and function of disgust (see Tybur, 2013; contrast with Rozin and Haidt, 2013 ). For example, this type of approach might be useful in unraveling some of the mysteries of moral disgust, which we have suggested reflects two phenomena: 1) the tendency for people to morally condemn others who engage in disgusting behaviors; and 2) the tendency for people to communicate moral condemnation with verbal and facial expressions of disgust. Ultimately, we believe that a systematic evolutionary approach can help integrate the impressive and growing body of research on disgust.

References

Becker, E. (1973). The denial of death. New York: Free Press.

Curtis, V., Aunger, R., & Rabie, T. (2004). Evidence that disgust evolved to protect from risk of disease. Proceedings of the Royal Society: Series B: Biological Sciences, 271(Suppl. 4), S131–S133. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2003.0144

Curtis, V., & Biran, A. (2001). Dirt, disgust, and disease: Is hygiene in our genes? Perspectives in Biology and Medicine, 44, 17–31. doi:10.1353/ pbm.2001.0001

Curtis, V., de Barra, M., & Aunger, R. (2011). Disgust as an adaptive system for disease avoidance behaviour. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society: Series B: Biological Sciences, 366, 389 – 401. doi:10.1098/rstb.2010.0117

De Smet, D., Speybroeck, L. V., & Verplaetse, J. (2013). The Westermarck effect revisited: A psychophysiological study of sibling incest aversion in young female adults. Evolution and Human Behavior. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2013.09.004

Fessler, D. M. T., & Navarrete, C. D. (2003a). Domain-specific variation in disgust sensitivity across the menstrual cycle. Evolution and Human Behavior, 24, 406 – 417. doi:10.1016/S1090-5138(03)00054-0

Haidt, J., Rozin, P., McCauley, C., & Imada, S. (1997). Body, psyche, and culture: The relationship of disgust to morality. Psychology and Developing Societies, 9, 107–131. doi:10.1177/097133369700900105

Lieberman, D., Tooby, J., & Cosmides, L. (2007, February 15). The architecture of human kin detection. Nature, 445, 727–731. doi:10.1038/nature05510

Miller, S. B. (2004). Disgust: The gatekeeper emotion. Mahwah, NJ: Analytic Press

Nabi, R. (2002). The theoretical versus the lay meaning of disgust: Implications for emotion research. Cognition & Emotion, 16, 695–703. doi:10.1080/02699930143000437

Olatunji, B. O., Adams, T., Ciesielski, B., Bieke, D., Sarawgi, S., & Broman-Fulks, J. (2012). The three domains of disgust scale: Factor structure, psychometric properties, and conceptual limitations. Assessment, 19, 202–225. doi: 10.1177/1073191111432881

Pinker, S. (2012). The false allure of group selection. Retrieved from http://www.edge.org

Royzman, E. B., & Sabini, J. (2001). Something it takes to be an emotion: The interesting case of disgust. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 31, 29 –59. doi:10.1111/1468-5914.00145

Rozin, P., & Haidt, J. (2013). The domains of disgust and their origins: contrasting biological and cultural evolutionary accounts. Trends in cognitive sciences. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2013.06.001

Rozin, P., Haidt, J., & McCauley, C. R. (2008). Disgust. In M. Lewis, J. M. Haviland-Jones, & L. F. Barrett (Eds.), Handbook of emotions (3rd ed., pp. 757–776). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Rozin, P., Haidt, J., & McCauley, C. R. (2009). Disgust: The body and soul emotion in the 21st century. In D. McKay & O. Olatunji (Eds.), Disgust and its disorders (pp. 9 –29). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Trivers, R. (1972). Parental investment and sexual selection. In B. Campbell (Ed.), Sexual selection and the descent of man, 1871–1971 (pp. 136 –179). Chicago, IL: Aldine-Atherton

Tybur, J. M. (2013). Cultural and biological evolutionary perspectives on disgust – oil and water or peas and carrots? Retrieved from http://www.epjournal.net/blog

Tybur, J. M., Bryan, A. D., Lieberman, D., Caldwell Hooper, A. E., & Merriman, L. A. (2011). Sex differences and sex similarities in disgust sensitivity. Personality and Individual Differences, 51, 343–348. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2011.04.003

Tybur, J. M., & De Vries, R. E. (2013). Disgust sensitivity and the HEXACO model of personality. Personality and Individual Differences, 55, 660-665. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2013.05.008

Tybur, J. M., Lieberman, D., Kurzban, R., & DeScioli, P. (2013). Disgust: Evolved function and structure. Psychological Review, 120, 65–84. doi: 10.1037/a0030778

Tybur, J. M., Lieberman, D., & Griskevicius, V. (2009). Microbes, mating, and morality: Individual differences in three functional domains of disgust. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97, 103–122. doi:10.1037/a0015474

Wagner, C. M., Stroud, E. M., & Meckley, T. D. (2011). A deathly odor suggests a new sustainable tool for controlling a costly invasive species. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, 68, 1157–1160. doi:10.1139/f2011-072