Swiss Center for Affective Sciences

With the rise of affectivism (Dukes et al., 2021), affective scientists are increasingly investigating the mechanisms that underly emotions and their interactions with cognitive processes such as attention, memory, and decision-making. While intense debates exist in our field, it seems to me that there are also important agreements that have been reached. I argue below that whereas most current theories of emotion adopt a “multiaspect” perspective to emotion, with feeling being one aspect (or component) of an emotion, the content of feelings remains debated. Below, I also discuss how understanding the relationship between the feeling component and the other components may help solve a secular debate in emotion research concerning the so-called James-Lange theory of emotion, and may also help frame new research questions.

Since at least Aristotle, the idea that the complexity of emotions can be understood with respect to more simple dimensions has been discussed in many of the various fields that now constitute the affective sciences. For instance, Aristotle’s idea that we experience pleasure and pain when we have emotions (e.g., Dow, 2015) is arguably present in most contemporary theories of emotions, with the term “valence” being typically used to refer to the displeasure /pleasure dimension(s). Other dimensions have been described as important when it comes to reducing the complexity of our emotional experiences; for instance, arousal, dominance, and unpredictability have all been suggested to underly emotions and other affective phenomena.

The explicit search for which elements can be considered as constituents of an emotion is not very recent (see e.g., McCosh, 1880; Irons, 1897), and in addition to the above-mentioned dimensions, emotion researchers have also described what we could refer to as “aspects” or “components” of emotions (see Sander, 2013). Although there are conceptual distinctions that could be proposed between the constructs of “dimensions” and “components”, what I aim at highlighting here is that it has often been suggested that one can decompose an emotion into some constituent elements. For instance, McCosh (1880) considered four elements to be involved in emotion: “First, there is the affection, or what I prefer calling the motive principle, or the appetence; (…) Secondly, there is an idea of something, of some object or occurrence, as fitted to gratify or disappoint a motive principle or appetence; (…) Thirdly, there is the conscious feeling; (…) Fourthly, there is an organic affection.” (McCosh, 1880, p. 1-4).

As can be seen from McCosh’s early componential approach to emotion, the conscious feeling was already suggested as one of several aspects of emotion almost 150 years ago. Focusing on definitions from the 20th century, Kleinginna and Kleinginna (1981) reminded us that, when considering the 11 categories of definitions of emotion that they established, the “multiaspect” category was the largest one. Indeed, this category included 32 definitions suggested by scholars of the 20th century who emphasized that “emotion contains several important components” (Kleinginna and Kleinginna, 1981, p. 352). While each major contemporary psychological theory keeps its specificities with respect to many principles that are proposed to govern an emotional episode, there seems to be a consensus among these theories about the general idea that emotions are multicomponential phenomena. Let us consider, for instance, Basic Emotion Theories, Core-Affect Theories, and Appraisal Theories.

For instance, Paul Ekman is a prominent representative of the Basic Emotion Theories, and according to Matsumoto and Ekman (2009, p. 69): “A match (…) initiates a group of responses, including expressive behaviour, physiology, cognitions, and subjective experience. The group of responses is coordinated, integrated, and organized, and constitutes what is known as an emotion. (…). In our view, the term ‘emotion’ is a metaphor that refers to this group of coordinated responses.”

A very different perspective in many respects, but similar in terms of a multicomponential approach, is the Core-Affect Theory, which insists on the idea that one should understand the psychological construction of emotions by considering several components. According to Jim Russell, who is a prominent representative of the Core-Affect Theories, “Psychological construction is not one process but an umbrella term for the various processes that produce: (a) a particular emotional episode’s ‘components’ (such as facial movement, vocal tone, peripheral nervous system change, appraisal, attribution, behaviour, subjective experience, and emotion regulation); (b) associations among the components; and (c) the categorisation of the pattern of components as a specific emotion.” (Russell, 2009, p. 1259). Arguably, when Matsumuto and Ekman (2009), and Russell (2009) use “subjective experience” as a component of emotion, they use it in the broad sense of “subjective feeling”.

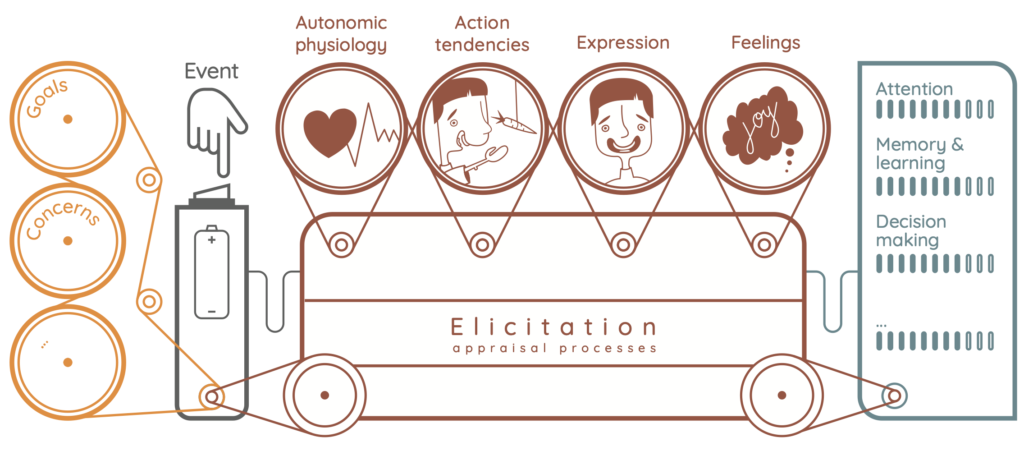

As a third family of theories of emotion, appraisal theories are different to the two previously mentioned theories in many ways but typically share the multicompoenential perspective. In this respect, the “Component Process Model” of emotion proposed by Scherer (1984; 2005) is certainly the appraisal theory that, since the 1980s, most explicitly emphasizes the role of various components of emotion. Indeed, “in the framework of the component process model, emotion is defined as an episode of interrelated, synchronized changes in the states of all or most of the five organismic subsystems in response to the evaluation of an external or internal stimulus event as relevant to major concerns of the organism.” (Scherer, 2005, p. 697). In Scherer’s approach, the 5 components are the cognitive component (appraisal processes), the physiological component (bodily symptoms), the motivational component (action tendencies), the motor expression component (facial and vocal expression), and the subjective feeling component (emotional experience). Not all components have the same status: one of them (the appraisal component) determines changes in the other four components (see also Moors, 2014), and the subjective feeling component integrates the activity of the other components (see Grandjean, Sander, and Scherer, 2008).

It is important to note that whether the feeling component is necessarily conscious can be a matter of conceptual discussion (see Grandjean, Sander, & Scherer, 2008). However, it seems to me that the terms “feeling,” “emotional consciousness,” or “emotional experience” are typically used interchangeably in the literature. Inspired by the multicomponential appaisal approach, Pool & Sander (2021) recently proposed Figure 1 as a general way to represent both the emotion components and their inter-relations: a particular event is first appraised by the individual according to their current concerns, values, and goals (motivational processes displayed in yellow). Then, this elicitation process can trigger an emotional response in multiple components: autonomic physiology, action tendency, expression, and feeling. The emotional processes (displayed in red) closely interact with several cognitive processes (displayed in blue) such as attention, memory, learning, and decision-making.

When measuring emotions, we typically use only a few measures (e.g., only self-reports, only psycho-physiological measures, only appraisal questionnaires, only action tendency questionnaires, only expression coding, or only approach-avoidance tendencies). The multicomponential approach suggests that any measure of emotion may only give a probabilistic account of emotion inference if one aims at measuring a specific emotion (e.g., fear, happiness, or awe), and that multiple measures would be needed to achieve converging evidence across the components of emotions (see Delpalnque & Sander, 2021). Indeed, single measures of emotions are not markers of emotions: there is a risk of making wrong reverse inferences when focusing only on single measures; this is why Delplanque & Sander (2021) argued that this risk is decreased when converging evidence is obtained from several components instead of only one. Other ways to measure emotions include measures of brain systems, with methods of high temporal (e.g., EEG) and spatial (e.g., fMRI) resolution.

Although further systematic investigation is needed, it seems to me that the existence of several components is consistent with the way the emotional brain is organized (see Sander, Grandjean, and Scherer, 2018). In fact, the study of the emotional brain (Adolphs & Anderson, 2018), and investigations of the neural networks involved in emotion is a lively development in the affective sciences (see Pessoa, 2018). In affective neuroscience, it has also been considered useful to separate the mechanisms involved in feeling from those involved in other emotional components (for discussion, see Damasio, 1998; Leitao et al., 2020; Sander, 2013), with the idea that some particular brain systems (e.g., the anterior cortical midline structures, see Heinzel et al., 2010) or some modes of interactions between several brain networks (e.g., Thagard and Aubie, 2008; Grandjean, Sander, and Scherer, 2008) allow the specific emergence of feelings.

Interestingly, adopting a multicomponential approach to emotion also appears to be useful beyond the study of emotion itself. For instance, another key domain in affective sciences is the study of emotion regulation mechanisms, and in this domain too, considering various components has proven useful, with different specific component-related strategies (e.g., reappraisal, expressive suppression, or physiological intervention) being studied and compared (see McRae & Gross, 2020). Another example of the usefulness of the multicomponential approach can be found in attempts to understand other affective phenomena than emotions; for instance, a distinction between “wanting” and “liking” components in reward processing (see Berridge & Kringelbach, 2015, Pool et al., in press) can be related to some components of emotion (see Sander, & Nummenmaa, 2021).

Considering the links between the feeling component and the other components leads to the complex question concerning the content of feelings. What are the inputs that are processed by the feeling component during an emotional episode?

In relation to this question, bridges between the Jamesian approaches to emotion and the multicomponential approaches to emotion may be particularly useful when it comes to solving a secular debate in emotion research: the peripheralist-centralist debate. James famously defined standard emotions as follows: “My thesis, on the contrary, is that the bodily changes follow directly the PERCEPTION of the exciting fact, and that our feeling of the same changes as they occur IS the emotion.” (James, 1884, p.189-190). It can be noted here that James mentioned both the notions of “bodily changes” and “feeling” in his definition: bodily states would be a necessary condition to actually feel the emotion. Importantly, James explicitly restricted his definitions to those emotions that have a distinct bodily expression (James, 1884, p.189; for discussion, see Friedman, 2010). This is noteworthy because, contrary to what is sometimes assumed, James’ definition was not about all emotions but only about this subset of emotions. This suggests that, even for James, some feelings could be elicited via another process.

The focus on the role of bodily changes in emotion and feeling is well known in theories of James, Lange and Sergi, but these ideas were also found before, and, obviously, developed later on (see Damasio, 1998; Damasio & Carvalho, 2013; Friedman, 2010). For instance, traces of the peripheralist view can be recognized in the writings of McCosh who, a few years before James, already wrote: “If it be true that emotion produces a certain bodily state, it is also true that some bodily states tend to produce the corresponding feeling” (McCosh, 1880, p. 105; see also Ruckmick, 1934). There is little doubt that James linked bodily changes to a particular aspect of emotion: the conscious aspect. Indeed, James’s (1894) introductory sentence is clear in this respect: “In the year 1884 Prof. Lange of Copenhagen and the present writer published, independently of each other, the same theory of emotional consciousness” (p. 516).

Therefore, the multicompential approach may help solving the debate of whether the bodily changes are a cause or a consequence of the emotion by considering feeling as a component: the feeling may be (at least partly) determined by a change in the body state, while the other components of emotion may not be caused this body state. For instance, according to Frijda (2005), the emotional experience “generally contains conscious reflections of the four major nonconscious components of the process of emotions: affect, appraisal, action readiness, and arousal. In addition, it may include the emotion’s felt ‘significance’” (p. 494). Assuming that an emotional experience is to be considered as synonymous with an emotional feeling, then it would suggest that, in addition to the bodily changes, the outcomes of the other components should also be considered when it comes to understanding the content of an emotional feeling. This may also mean that, just like one can have a physiological feeling (e.g., feeling of an increased heart rate), one could also have a feeling of appraisal outcomes (e.g., feeling of uncertainty).

Interestingly, in addition to using interoception to feel physiological processes that are not emotional (e.g., hunger, thirst, well-being, cold, or fatigue, see Damasio and Carvalho, 2013; Pace-Schott et al., 2019), one may also feel outcomes of cognitive processes (e.g., feeling of remembering). Following James, there may be emotional experiences that cannot be explained in terms of felt distinct bodily expressions; these experiences could also be explained by a model considering that not only bodily changes can be felt, but that appraisals or action tendencies can also be felt. This would correspond to an extension of the view suggested by Damasio and Carvalho (2013) according to whom “Feelings are mental experiences of body states” (p. 143). They suggest that drives and emotions can elicit feelings, but that their definition also excludes the use of “feeling” in the sense of “thinking” or “intuiting”. With this view, a research question is therefore whether appraisal outcomes or action tendencies can be felt as direct inputs, or whether they would be felt only via bodily changes.

To conclude, it seems to me that the multicomponential approach to emotion has the potential to bring affective scientists together showing that, despite the useful diversity of theories of emotions, there is a general framework that can be shared. As emotion researchers, we tend to focus on specific processes or components, and study for instance appraisal/elicitation processes, expressions, autonomic responses, action tendencies, or feelings in relative independence. Therefore, a better understanding of the relationships between the components of an emotional episode would also be a way to further the disciplinary and interdisciplinary collaborations between affective scientists who specialize in the study of different components.

In other words, bringing the components together would also bring researchers together. Among the numerous questions that such a framework can support, we can cite a few: How do the components interact together (e.g., in terms of psychological mechanisms, brain networks, and dynamic systems)? How does the inter-relation between components represent specific emotions (e.g., fear or pride)? Are there different weightings of the components as inputs to the feeling component for different emotions (e.g., with bodily states being more weighted for “basic” emotions than for other emotions)? Are some components typically unconscious (e.g., autonomic physiology) while others are typically conscious (e.g., feeling)? How do the components and their relations develop over time, both phylogenetically and ontogenetically? How do the components, and their sub-processes, specifically explain the differential effects of emotions on many cognitive mechanisms and on behaviours? It seems to me that such questions, and many others, while having their roots in historical theories of emotion, have the potential to use multicomponential approaches in order to bring new answers for a better general understanding of emotion.

References

Adolphs, R., & Anderson, D. J. (2018). The Neuroscience of Emotion: A New Synthesis. Princeton University.

Berridge, K. C. & Kringelbach, M. L. (2015). Pleasure systems in the brain. Neuron 86, 646–664 (2015).

Damasio, A. R. (1998). Emotion in the perspective of an integrated nervous system. Brain Research Reviews, 26(2–3), 83-86.

Damasio, A., & Carvalho, G.B., (2013). The nature of feelings: evolutionary and neurobiological origins. Nature Reviews Neuroscience,14, 143–152.

Delplanque, S., & Sander, D. (2021). A fascinating but risky case of reverse inference: from measures to emotions! Food Quality and Preference, 92, 104183.

Dukes, D., Abrams, K., Adolphs, R., Ahmed, M. E., Beatty, A., Berridge, K. C., Broomhall, S., Brosch, T., Campos, J. J., Clay, Z., Clément, F., Cunningham, W., Damasio, A., Damasio, H., D’Arms, J., Davidson, J., de Gelder, B., Deonna, J., de Sousa, R., Ekman, P., Ellsworth, P., Fehr, E., Fischer, A., Foolen, A., Frevert, U., Grandjean, D., Gratch, J., Greenberg, L., Greenspan, P., Gross, J., Halperin, E., Kappas, A., Keltner, D., Knutson, B., Konstan, D., Kret, M., LeDoux, J., Lerner, J., Levenson, R. W., Loewenstein, G., Manstead, A., Maroney, T., Moors, A., Niedenthal, P., Parkinson, B., Pavlidis, I., Pelachaud, C., Pollak, S., Pourtois, G., Röttger-Rössler, B., Russell, J. A., Sauter, D., Scarantino, A., Scherer, K., Stearns, P., Stets, J., Tappolet, C., Teroni, F., Tsai, J., Turner, J., Van Reekum, C., Vuilleumier, P., Wharton, T., & Sander, D. (2021). The rise of Affectivism. Nature Human Behaviour, 5, 816–820.

Dow, J. (2015). Aristotle’s Theory of the Passions—Passions as Pleasures and Pains. In J. Dow (2015), Passions and Persuasion in Aristotle’s Rhetoric, Oxford University Press.

Friedman, B.H. (2010). Feelings and the body: the Jamesian perspective on autonomic specificity of emotion. Biological Psychology, 84, 383–393.

Frijda, N.H. (2005). Emotion experience. Cognition & Emotion, 19, 473-498.

Grandjean, D., Sander, D., & Scherer, K. R. (2008). Conscious emotional experience emerges as a function of multilevel, appraisal–driven response synchronization. Consciousness and Cognition, 17(2), 484-495.

Irons, D. (1897). The primary emotions. The Philosophical Review, 6, 626–645.

James, W. (1884). What is an emotion? Mind, 9, 188-205.

James, W. (1894). The physical basis of emotion. Psychological Review, 1, 516- 529.

Kleinginna, P. R. Jr., & Kleinginna, A. M. (1981). A categorized list of emotion definitions with suggestions for a consensual definition. Motivation and Emotion, 5, 345-379.

Leitao, J., Meuleman, B., Van De Ville, D., & Vuilleumier, P. (2020). Computational imaging during video game playing shows dynamic synchronization of cortical and subcortical networks of emotions. Plos Biology, 18(11), e3000900.

Matsumoto, D. & Ekman, P. (2009). Basic emotions. In D. Sander and K.R. Scherer (Eds.). The Oxford Companion to Emotion and the Affective Sciences (pp. 69-72). New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press.

McCosh, J. (1880). The Emotions, New York: Charles Scribners’sons.

McRae, K., & Gross, J. J. (2020). Emotion regulation. Emotion, 20(1), 1-9.

Moors, A. (2014). Flavors of appraisal theories of emotion. Emotion Review, 6(4), 303–307.

Pace-Schott, E. F., Amole, M. C., Aue, T., Balconi, M., Bylsma, L. M., Critchley, H., Demaree, H. A., Friedman, B. H., Gooding, A. E. K., Gosseries, O., Jovanovic, T., Kirby, L. A. J., Kozlowska, K., Laureys, S., Lowe, L., Magee, K., Marin, M.-F., Merner, A. R., Robinson, J. L., . . . VanElzakker, M. B. (2019). Physiological feelings. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 103, 267–304.

Pessoa, L. (2018). Emotion and the Interactive Brain: Insights From Comparative Neuroanatomy and Complex Systems. Emotion Review, 10(3), 204–216.

Pool, E. R., Munoz Tord, D., Delplanque, S., Stussi, Y., Cereghetti, D., Vuilleumier, P., & Sander, D. (in press). Differential contributions of ventral striatum subregions in the motivational and hedonic components of affective processing of reward. The Journal of Neuroscience.

Pool, E. R., & Sander, D. (2021). Emotional learning: Measuring how affective values are acquired and updated. In H. L. Meiselman (Ed.), Emotion measurement (2nd ed., pp. 133-165). Woodhead Publishing.

Ruckmick, C. A. (1934). McCosh on the emotions. The American Journal of Psychology, 46, 506–508.

Russell, J. A. (2009). Emotion, core affect, and psychological construction. Cognition & Emotion, 23(7), 1259 -1283.

Sander, D. (2013). Models of emotion: The affective neuroscience approach. In J. L. Armony & P. Vuilleumier (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of human affective neuroscience (pp. 5-53). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Sander, D., Grandjean, D., & Scherer, K. R. (2018). An appraisal-driven componential approach to the emotional brain. Emotion Review, 10(3), 219-231.

Sander, D., & Nummenmaa, L. (2021). Reward and emotion: An affective neuroscience approach. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 39, 161-167.

Scherer, K. R. (1984). On the nature and function of emotion: A component process approach. In K. R. Scherer, & P. Ekman (Eds.), Approaches to emotion (pp. 293–317). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Scherer, K. R. (2005). What are emotions? And how can they be measured? Social Science Information, 44(4), 695-729.