Department of Psychology and Neuroscience

Living in communities is not easy; to co-exist successfully we must understand and follow certain norms or risk being shunned by our groups. Such norm understanding begins to emerge remarkably early in life1–3. Norms aimed at preserving the rights and welfare of others belong to the moral domain; norms aimed at preserving the social coordination of groups belong to the conventional domain. At around three years of age, young children start to distinguish moral from conventional norms4,5 and even show differential arousal to moral violations (e.g., destruction of property) than conventional violations (e.g., playing a game wrong)6.

Some classic developmental theories in psychology have assumed that norms about fairness fall in the moral domain, the reasoning being that issues of fairness are naturally tied to justice, rights, and welfare7–11. For example, moral philosophers such as Rawls12,13 have positioned justice as the fundamental moral concern. Therefore, in research and theorizing about norms, fairness has typically been classified at the outset with other moral norms such as those concerning physical or property harm5. Yet, converging research across economics and psychology also shows that children and adults do not hold a strict view of fairness, but rather perceive the acceptability of unfairness on a continuum14–19. This stands in contrast to children’s and adults’ views on morality, which are generally less variable and less flexible. Therefore, the current literature does not support the assumption that fairness falls within the moral domain.

Understanding how children perceive fairness norms could also help us think more critically about the current state of inequality in the world. Income inequality in the U.S. has worsened over the past 50 years20. Yet, across the political aisle, people are divided on how fair they view this resource distribution21. Those who perceive the status quo as a violation of the norm are more sensitive to the harm caused by unfairness, and those who see no violation are less sensitive to the harm/affect22,23. Although violations that involve harm to others are perceived to be moral violations24–26, much less is known about how perceptions of harm/affect may motivate people’s responses to fairness violations22.

This dissertation provides the first explicit empirical study of these competing perspectives. I focus here on two studies (Studies 3 and 5a), that aim to characterize children’s and adults’ evaluations of unfairness and the role perceived harm in fairness norm evaluations.

Methods

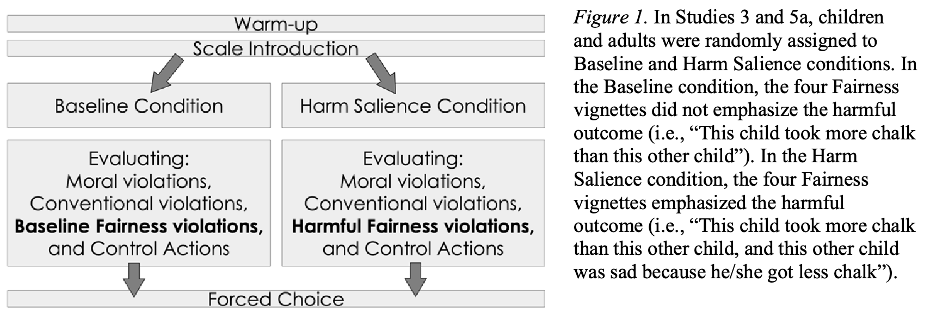

The full procedure for Study 3 (children) and 5a (adults) can be found in Figure 1.

In Study 3 (N=66 4-year-olds, M=53.4 months, 29 girls) and Study 5a (N=211 adults, M=19.2 years, 141 female) participants were randomly assigned to Baseline or Harm Salience conditions. Harm was manipulated only for the Fairness transgression type (see Fig. 1). In a randomized order, participants saw a total of 16 videos depicting three sets of transgressions (4 Moral, 4 Conventional, and 4 Fairness) and a set of control actions (4 Control). Participants were asked to evaluate the scenario using a 9-point scale. Then, participants were asked to group fairness vignettes with moral or conventional vignettes.

Results

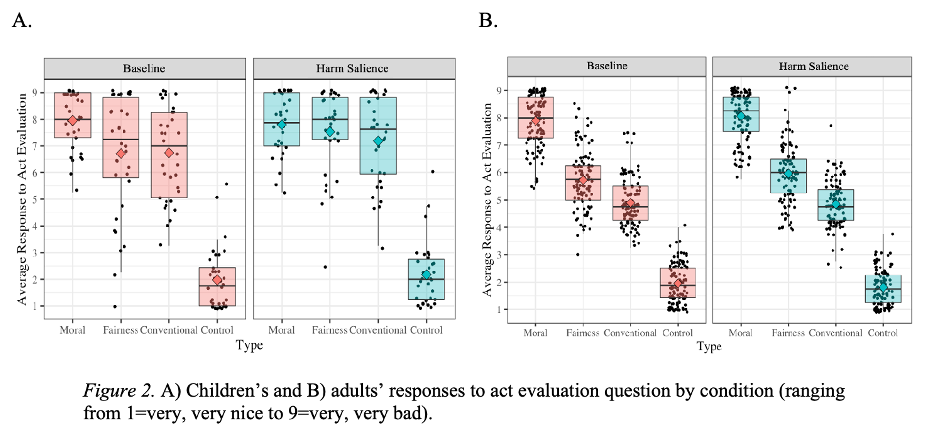

In Study 3, there was a significant main effect of condition for fairness evaluations, such that children in the Harm Salience condition evaluated unfairness more negatively than children in the Baseline condition, t(230)=2.18, p =.030 (Fig. 2A). Children in the Baseline condition rated the seriousness of transgressions as follows: Moral>Fairness=Conventional>Control. Children in the Harm Salience condition the seriousness of transgressions as follows: Moral=Fairness= Conventional>Control.

In Study 5a, adults in the Harm Salience condition evaluated unfairness marginally more seriously than those in the Baseline condition, t(690)=1.90, p=.057 (Fig. 2B). Although this difference was not significant, it was in the predicted direction. Adult participants in both conditions evaluated the seriousness of transgressions as follows: Moral>Fairness>Conventional>Control.

Discussion and Summary

Fairness norms have been assumed to be part of the moral domain, despite no conclusive evidence in support of that claim. This dissertation sought to challenge our understanding of fairness norms. I reasoned that how we conceptualize fairness will, in turn, affect how we respond to it. For example, if we perceive unfairness to be similar to harming others, we may be more likely to intervene and rectify it. However, if we perceive unfairness to be similar to wearing pajamas to school, we may not perceive it as a serious violation or rectify the harm done to the disadvantaged individual (or group). These studies explain why children – and even adults – may not evaluate unfair distributions as negatively as other moral violations, namely, the indirect and less perceptible harm caused by unfairness. Therefore, it might be better to examine the moral/conventional distinction not from a domain theory perspective but as a continuum.

Another aim of the current investigation was to examine the role harm/affect plays in children’s and adults’ moralization of fairness norms. The results suggest that, as hypothesized, emphasizing harmful outcomes of unfairness shifts judgments in the moral direction. Although this was not the focus of the current set of studies, using the same logic, we may also hypothesize that minimizing harm would shift transgressions to be less moral 28. These findings are consistent with the evolutionary accounts, such that harm salience may intuitively allow us to distinguish

norms that are more important for our welfare and lead to fair distributions.

The studies presented here seek to break new ground by using experimental methods to establish how children’s understanding of fairness changes and compares to moral or conventional norms. Understanding how children perceive, when children perceive, and why children perceive fairness as a moral or conventional norm, could help us better understand how fairness is conceptualized. The findings have the potential to inform and influence educational programming—including school curricula designed for specific developmental periods—to socialize and maintain fairness concerns from early in development.

Children are sensitive to (un)fair distributions of resources. These studies explain why children – and even adults – may not evaluate unfair distributions as negatively as other moral violations, namely, the indirect and less perceptible harm caused by unfairness. They suggest a potential explanation for why resource inequality is widely accepted in many societies. They also point to a potential solution: Emphasizing and making explicit the harm caused by unfairness.

References

1. Smetana, J. G., Jambon, M. & Ball, C. The social domain approach to children’s moral and social judgments. in Handbook of moral development (2nd ed.) (eds. Killen, M. & Smetana, J. G.) 23–45 (2014).

2. Turiel, E. Social regulations and domains of social concepts. New Dir. Child Adolesc. Dev. 1978, 45–74 (1978).

3. Yucel, M. & Vaish, A. Young children tattle to enforce moral norms. Soc. Dev. 27, 924– 936 (2018).

4. Ball, C. L., Smetana, J. G. & Sturge-Apple, M. L. Following my head and my heart: Integrating preschoolers’ empathy, theory of mind, and moral judgments. Child Dev. 88, 597–611 (2017).

5. Nucci, L. P. & Turiel, E. Social interactions and the development of social concepts in preschool children. Child Dev. 49, 400–407 (1978).

6. Yucel, M., Hepach, R. & Vaish, A. Young children and adults show differential arousal to moral and conventional transgressions. Front. Psychol. 11, (2020).

7. Turiel, E. The development of social knowledge: Morality and convention. (Cambridge University Press, 1983).

8. Turiel, E., Killen, M. & Helwig, C. C. Morality: Its structure, functions, and vagaries. in The emergence of morality in young children (ed. Kagan, J.) 155–243 (University of Chicago Press, 1987).

9. Smetana, J. G. & Ball, C. L. Young children’s moral judgments, justifications, and emotion attributions in peer relationship contexts. Child Dev. 89, 2245–2263 (2018).

10. Damon, W. Measurement and Social Development. Couns. Psychol. 6, 13–15 (1977).

11. Piaget, J. The moral judgment of the child. The Moral Judgment of the Child (1932).

12. Rawls, J. A theory of Justice. (Oxford University Press, 1999).

13. Rawls, J. Some Reasons for the Maximin Criterion. Am. Econ. Rev. 64, 141–146 (1974).

14. Fehr, E. & Schmidt, K. M. A theory of fairness, competition, and cooperation. Q. J. Econ. 271–296 (1999) doi:10.2307/j.ctvcm4j8j.14.

15. Fehr, E. & Gächter, S. Cooperation and punishment in public goods experiments. Am. Econ. Rev. 90, 980–994 (2000).

16. Adams, J. S. Towards an understanding of inequity. J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol. 67, 422–436 (1963).

17. Hochman, G., Ayal, S. & Ariely, D. Fairness requires deliberation: The primacy of economic over social considerations. Front. Psychol. 6, 1–7 (2015).

18. Güth, W., Schmittberger, R. & Schwarze, B. An experimental analysis of ultimatum bargaining. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 3, 367–388 (1982).

19. Sanfey, A. G., Rilling, J. K., Aronson, J. A., Nystrom, L. E. & Cohen, J. D. The neural basis of economic decision-making in the Ultimatum Game. Science (80-. ). 300, 1755–1758 (2003).

20. U.S. Census Bureau. Income and poverty in the United States: 2018. Current Population

Reports https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2019/demo/p60-266.html (2018).

21. Pew Research Center. 2018 midterm voters: Issues and political values. https://www.people-press.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2018/10/Values-for-release.pdf (2018).

22. Mikołajczak, G. & Becker, J. C. What is (un)fair? Political ideology and collective action. J. Soc. Polit. Psychol. (2019).

23. Dietze, P. & Craig, M. A. Framing economic inequality and policy as group disadvantages (versus group advantages) spurs support for action. Nat. Hum. Behav. (2021) doi:10.1038/s41562-020-00988-4.

24. Schein, C. & Gray, K. The theory of dyadic morality: Reinventing moral judgment by redefining harm. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 22, 32–70 (2018).

25. Gray, K., Young, L. & Waytz, A. Mind perception is the essence of morality. Psychol. Inq. 23, 101–124 (2012).

26. Gray, K., Waytz, A. & Young, L. The moral dyad: A fundamental template unifying moral judgment. Psychol. Inq. 23, 206–215 (2012).

27. Holm, S. A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scand. J. Stat. 6, 65–70 (1978).

28. Zelazo, P. D., Helwig, C. C. & Lau, A. Intention, act, and outcome in behavioral prediction and moral judgment. Child Dev. 67, 2478–2492 (1996).